Transition to university in 2022

Throughout 2020 and much of 2021, students will have had variable school experiences, with fewer opportunities to learn study skills, exam techniques, and subject knowledge as a result of school closures and exam cancellations. Their experiences of years 11 and 12 will have been socially disrupted too, which will have had a huge impact on their mental health (Orben et al., 2020). It is therefore vital to consider how to support first-year students in semester 1 2022 to ensure they have the most supportive and engaging experience possible.

With this in mind, it’s worth considering the importance of designing activities and assessments that are known to support a successful transition to tertiary education. Assessment is a key driver of learning, so it makes sense to be particularly careful with its design and to reflect on our current practice given the unique cohort who will begin their studies in 2022.

First-year assessment at Sydney

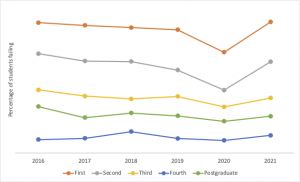

The graph opposite (a) shows that fail rates in first-year units at the University of Sydney are considerably higher than for other years. Worryingly, it also shows a large increase in first-year students for semester 1, 2021, corresponding to the students who started with us after the first year of interrupted schooling due to the pandemic.

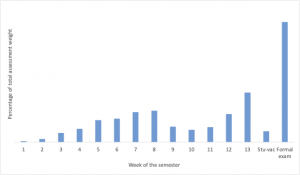

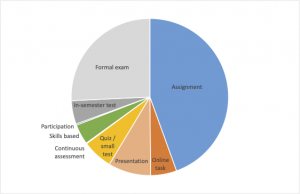

Assessments in our first-year units tend to be heavily weighted towards the end of semester, with formal exams playing a key role. Depending on the discipline, these may rely on multiple-choice and other auto-marking question types. The figures below show (b) the percentage of the total assessment weight by week of the semester and (c) the breakdown of assessment by type across all first-year units. There is considerable variation in the assessment used across our faculties and schools.

Designing assessment for student success in first-year

We know from the psychology literature that there are a number of conditions under which students thrive at tertiary education. In Lizzio’s “Five Senses of Student Success” model (Chester et al., 2013; Lizzio, 2006), students’ success in university can be generally categorized as relating to their capability, connectedness, purpose, resourcefulness, and culture (see Learning to learn after lockdown: the transition journey from alpha to omega). For students starting in 2021, ensuring that they feel a sense of belonging, encouraging their sense of self-efficacy and designing activities and classrooms that support their needs is vital.

Well-designed assessment can be used to facilitate first-year students making their social and academic transition to university.

In 2009, Professor David Nicol prepared a framework for first-year assessment practices that included 12 principles. In her 2018 paper, Theda Thomas revisited Nicol’s principles to analyse how current practices are addressing Nicol’s first-year assessment principles, whether there were any issues in implementing them and whether anything new is emerging in the field. The following is a summary of her findings, practical examples, and some suggestions for reworking the principles.

Applying best practice principles when designing assessment

1. Help to clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, standards)

Consider using exemplars and get students to use rubrics (or criteria) to evaluate these. This can assist with the development of evaluative judgement. Students in 2022 will be reacclimatising to study and it will be important to consider student capabilities and match expectations with their previous educational experiences. Given the disrupted nature of their pre-university experiences, it will be especially important to provide clear communications and expectations.

2. Encourage ‘time and effort’ on challenging learning tasks

Use staged assessment tasks so that students receive feedback on one task or part of a task before undertaking the next. Activities scheduled appropriately throughout the semester give students opportunities to practise skills required for assessment (Baker & Zuvela, 2013; Bell et al., 2013; Leung, Hashemi Pour, Reynolds & Jerzak, 2015). Using low-stakes formative assessments and active learning and teaching ensures students are engaged in their studies and helps them gain confidence (Boitshwarelo et al. 2017) and purpose.

3. Deliver high-quality feedback information that helps learners to self-correct

Feedback is a thorny issue. Feedback will have little impact if it is poor quality or if students do not know how to use it. Denton and Rowe (2015) suggest that feedback needs to include interaction and found that using a transmission form of feedback, where the lecturer provides feedback without any interaction, did not improve students’ performance. They suggest using a more dialogic style of feedback – examples include using staged assessments so that students are able to engage and act upon feedback to refine/improve their work before final submission.

Actionable and timely feedback will be even more vital in 2022 due to the introduction of the Job Ready Graduates Package and the need to regularly support this cohort’s return to study.

4. Provide opportunities to act on feedback (to close any gap between current and desired performance)

Encourage students to act upon feedback by ensuring it is actionable. If feedback is given at the end of an assessment there’s no possibility of using it. In their study on students’ perceptions of feedback, Denton and Rowe (2015) found that very few students reported using their feedback. They suggest using positive feedback that offers reassurance and provides advice on how to improve. Socratic questioning (in comments or in class) may be valuable in initiating dialogues about feedback (Wharton, 2013). One way of ensuring that students act on feedback is to oblige them to interact with the feedback before they undertake the next task. For example, Crimmins et al. (2016), included a reflection on feedback activity where students were asked to determine what the feedback indicated and identify areas for improvement. This was then used to formulate questions for their tutor in a face-to-face session. For more examples of improving feedback see Managing timely feedback and marking.

5. Ensure that summative assessment has a positive impact on learning

Unfortunately, Surgenor (2013) found that when examinations comprised a large percentage of the final grade in a subject, students perceived assignments through the year as ‘precursors to the real assessment’ rather than learning opportunities (p.299). Reducing the emphasis on large summative examinations in favour of meaningful assessment promotes self-efficacy (Lizzio and Wilson, 2008), rather than anxiety, and thus reduces known barriers to connectedness and belonging. As an alternative to traditional exams, consider using an oral summative assessment, so tutors can deal with specific issues directly at the time of the exam (Iannone and Simpson, 2015). This principle might be rephrased as: ‘ensure that all assessment has a positive impact on learning’. Consider using alternatives to final exams.

6. Encourage interaction and dialogue around learning (peer and teacher-student)

Consider using peer review to help students understand the marking criteria or provide feedback to students before submitting their final task. McDonnell and Curtis (2014) used an adaption of the peer review process which they termed ‘democratic’. In this schema student pairs evaluated their own and the other’s work and then met with the lecturer to determine the mark each should get. They argue that the incorporation of dialogue helped students to self-regulate and improved subsequent work. Although peer review can be challenging to implement, it is useful for helping students to become independent learners and develop evaluative judgement of their own and others work. Grading students’ peer reviews may help to improve the effort students expend and the quality of their critique (Hodgson et al., 2014; Kearney et al., 2016).

Peer and teacher-student dialogue helps to build a positive learning environment and community as well as being at the heart of trustful teacher-student relationships.

7. Facilitate the development of self-assessment and reflection in learning

Students need opportunities to practise judging their own work to develop their assessment literacy. Smith et al (2013) designed a 50-minute activity where students applied an assessment rubric to actual examples of student work that exemplified extremes of standards (e.g. poor, excellent). This study indicated that the greatest predictor of enhanced student marks (on the assessment task that was the subject of the experiment), was the development of their ability to judge standards of performance on student work created in response to a similar task. Consider using a scaffolded approach to judging work by introducing the concept for smaller tasks.

Actively providing students with the opportunities to understand assessment rules and what constitutes quality work also helps build resourcefulness – knowledge of the ‘hidden curriculum’ of university rules and expectations – and ultimately independence.

8. Give choice in the topic, method, criteria, weighting or timing of assessments

Nicol proposed that providing students with choice empowers them and encourages them to be creative or undertake in-depth learning. Perhaps not surprisingly, very few papers proposed giving students choice in criteria, weighting or timing of assessment tasks. Surgenor (2013) surveyed students about their assessment preferences and found that they preferred a broad range of assessment methods spread through the semester.

Choice of method or criteria may not be appropriate at first year, where educators need to provide guidance to students and spend time making sure that they understand assessment expectations. First-year cohorts are often large, and choice may make management complex and be confusing for students. On the other hand, the need for flexible, future-oriented learning experiences that offer students choice and cater for their diversity is acknowledged (Wanner & Palmer, 2015).

Perhaps this principle should be reworded to say: Provide students with choice in assessment to cater for student diversity? The advantage of this wording is that it allows flexibility of assessment to cater for students from different backgrounds or abilities without suggesting that this must be linked to specific attributes of the assessment task (topic, method, criteria, weighting or timing). By requiring students to include ideas and evidence related to their backgrounds and interests in their answers enables all students to develop purpose. In addition, stress the relevance of the assessment and why it is important, ideally by relating it to their professional or personal values.

9. Involve students in decision-making about assessment policy and practice.

Nicol acknowledges that involvement of first-year students in policy-making is rare, suggesting that students should be asked to provide feedback on their assessment experiences to foster improvement. For this principle to be more attainable, it could be revised to say: Use student feedback to improve assessment policies and practices. The idea of students as partners with academics in their learning is one that is gaining momentum in higher education (Matthews, Groenendijl, & Chunduri, 2017). Consider using student feedback, perhaps through focus groups to improve assessment year by year. Consistent with Principles 6 and 7, dialogue about assessment policy practice can also help students unpack and understand the ‘hidden’ rules.

10. Support the development of learning groups and communities.

Consider incorporating meaningful group assessments if possible. For example, Leung et al. (2015) implemented a model for four-person teams learning how to use an oscilloscope, with only one member from each team being evaluated, reducing marking time by 75%. The method had the advantages of enhancing students’ collaborative skills and reducing the time and resources required in the laboratory. Varsavsky and Rayner (2013) implemented an advanced-level assessment task for high-achieving students in biology and chemistry (see Principle 8), with the former involving solitary students and the latter using groups. They observed that students’ comments indicated that group activities added social integration and enjoyment to the project that was missing from the experience of solitary students. Such an approach helps foster a learning community, connectedness and belonging.

11. Encourage positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem.

It is essential that students feel motivated in the first year, as motivation is ‘linked to self-confidence, self-efficacy… and self-esteem’ (Nicol, 2009, p.40). He suggests that self-esteem and motivation are enhanced when students experience success early in the program by focusing on what they have learnt rather than their performance. It is vital to support first years by providing them with feedback that they can act upon (Gill, 2015). Potter and Bye (2014) noted that if students do poorly this may affect their commitment and confidence, generating increased rates of attrition. They stress the importance of motivating students to participate in support activities provided for those who have problems. Lizzio and Wilson (2013) undertook research with 257 first-year students to determine how students evaluate assessment tasks and how this affects their motivation and performance, finding that motivational content and perceived value of a task predicted their level of engagement, which was the only predictor of students’ grades.

Given the ongoing effects of lockdown and remote schooling on students’ mental health, self-efficacy and preparedness for university studies, it is more important than ever to ensure that barriers to connectedness and belonging, especially anxiety and low motivation are considered in assessment design.

12. Provide information to teachers that can be used to help shape their teaching.

Assessment should provide information to students about their learning, but also provide information to teachers so that they can adapt to meet the needs of their students. Crimmins et al (2016) report that teachers changed their teaching as a result of using the written, reflective and dialogic feedback (WRDF) strategy, which uses face-to-face meetings as part of their feedback strategy, with teachers reporting that feedback in these sessions was mutually beneficial and that students gave them information that enabled them to improve their teaching and subsequent feedback. Principle 12 could be reworded to: Use students’ performance and feedback to enhance teaching and curriculum design to meet the needs of learners.

Given the uneven effects of remote schooling in 2020 and 2021, early feedback also provides educators with information to act and to ensure ‘in-flight’ alignment of expectations and capabilities.

—

Finally, one aspect of first-year assessment not addressed by Nicol is the need to use assessment to introduce students to the multiple academic discourses and conventions of higher education (Beatty et al., 2014; Palmer et al., 2014; Yager et al., 2013). In 2022, educators need to consider how to address the inequalities of students’ experiences during the pandemic to ensure that they can successfully engage in and obtain this sense of academic culture. Assessment at first-year should be used to introduce students to the discourses and ways of thinking within a discipline, however, Hamilton (2016) warns against having excessively high expectations of first-year students and highlights the need to scaffold learning of academic literacies.

To achieve this, consider using authentic assessment tasks linked to the discipline to introduce students to conventions that are relevant to their future professions. First-year assessment should both introduce students to the ways of thinking in the discipline and highlight the expectations of assessment in higher education. Thomas (2018) suggests that a draft wording for a new principle would be: Engage students with the academic discourses and conventions of the discipline, higher education and their future profession.

Tell me more

- Come along to the Future of assessment forum on 19th November 2021

- Enrol in the MPLF module 05 Assessment and feedback for learning running in November

- Book a consultation for advice on how to re-design your assessment.

5 Comments