In 2020, a group of student co-designers partnered with the University of Sydney’s Educational Innovation team to develop Get Prepared, a learning resource supporting the transition of students to the University of Sydney, with a particular focus on assisting low-SES, first-in-family and Indigenous students. In this article, the students share their perspectives on the co-design process, including the dos and don’ts of staff working alongside students, the importance of students’ autonomy, the challenges that come with scaffolding tasks, and the online platforms that helped the team to work together in the challenging circumstances created by COVID-19. It is an incredibly valuable insight for staff looking to engage students as partners in their projects.

This article was contributed by student members of the Get Prepared team (Tiarna Scerri, Matilda Langford, Christine Hindeleh, Robert Tran, Michelle Cheung, Florence Borbe, Mahmoud Al-Rifai).

Setting the scene – Tiarna Scerri

Picture this – a dynamic cohort of students, educational designers, and teachers. Each individual possesses a unique voice shaped by their background and experience. Imagine a forum through which these voices cohesively blend together to become a choir of innovative change.

This dynamic picture represents the possibilities of working with students, “a highly-facilitated, team-based process in which teachers, researchers, and developers work together in defined roles to design an educational innovation” (Penuel et al, 2007). Read on as we discuss (1) the challenges of working with students-as-partners in the context of COVID-19, (2) prioritising student autonomy, and (3) the importance of clear instruction in scaffolding the content students create.

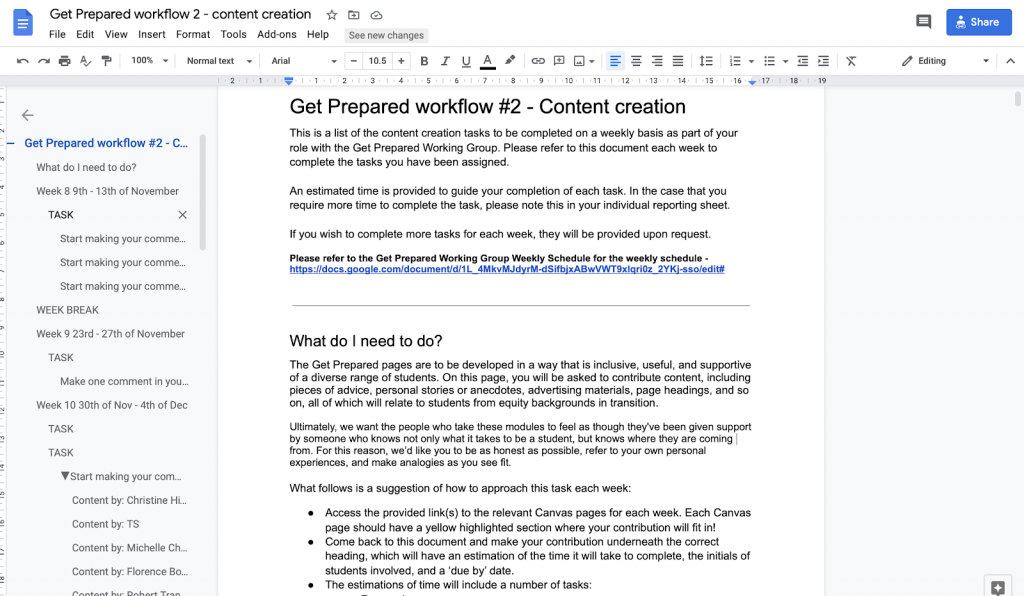

In our context, these scaffolds were created by our colleagues in Educational Innovation (EI) and consisted of breaking the site into distinct modules and creating a series of Google Docs for students to create and review content. Students met with the EI team weekly to discuss the design process and worked across these scaffolds over four months. In the true spirit of iterative co-design, the finished Get Prepared site evolved significantly from the initially conceived scaffold. Reflecting on this challenging but rewarding process, we offer the following insights into the collaborative experience.

The importance of autonomy – Matilda Langford

Driven by best practice in equity student support, Get Prepared draws upon a diverse range of worldviews, experiences, and voices in the student co-design team. Each of us was encouraged to incorporate unique insights about ourselves, our families and even our friends, drawing our individuality into the design process and shaping the end result.

Accessibility and representation were taken seriously from the onset of site development, with solutions to design issues negotiated and implemented thoroughly. Student co-designers from first-in-family or non-English speaking backgrounds were encouraged to critique the family, carer, and community-facing module, in particular, to make it as accessible as possible. Colour schemes or GIFS that hindered students with dyslexia were assessed and amended. These decisions validated our opinions and encouraged us to be creative, take risks, and go beyond the status quo in our advice and revisions.

As an Indigenous student, there have been many occasions where I have experienced a lot of content made about Indigenous people, but a complete lack of necessary content made for Indigenous people.

Unfortunately, this is prevalent in many academic spaces. There have been countless instances where, while searching for culturally competent support services and university resources, it has been difficult to sift through links, which lead to reports, which lead to more links. Eventually, you come up with nothing really helpful for an Indigenous student at all.

Initially, Get Prepared looked like more of the same. The first iteration of the Find Support When You Need It page only provided a sentence on support for Indigenous students prompting them to follow a link which led to a sparse and confusing page about what the University of Sydney does to engage and support Indigenous students. This would appear to be completely satisfactory to a non-Indigenous person. However, as an Indigenous student, who knows the range of what the University of Sydney really offers its Indigenous students (if you know how to look for it), I knew that the link was incapable of providing incoming Indigenous students with the information they needed. Upon identifying this ‘hidden curriculum’ moment, I was able to rewrite the section, giving an extensive summary of what support services and networks are available for Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander students.

The summary was incredibly well received in the co-design process and was included in the final version of the page, alongside several more detailed embedded links. Without an Indigenous student with experience in these areas, this would have remained an oversight. This co-design process reflects that, as recognised in a partnership project at the University of Wollongong, Indigenous-focused projects need to collaborate with Indigenous students.

To revise the Disability Services section of Find Support Where You Need It, I made a similar suggestion. Often, students with general learning disabilities, mental health issues, or more minor visual impairments may not realise that they are eligible for assistance with Disability Support. For example, I didn’t realise that my dyslexia is something I could request help for until the end of my first year at university.

Like before, I noticed that the Disability Services section only provided a prompt to follow a link. I knew that most students would not realise that they may be potentially eligible for these resources, so I recommended that a section be included which gives a general outline of what is considered a disability and what resources are on offer.

This wasn’t a time-consuming or tedious task. It was just something that might have been missed if someone with that lived experience was not working on the project. I believe this will be incredibly beneficial to those students like myself, who aren’t quite sure whether they can access help, but definitely need it.

Each of the diverse perspectives of the student contributors ensured that Get Prepared provides assistance for incoming students from diverse backgrounds.

Student autonomy was respected and encouraged throughout, creating a really productive and cohesive environment which made a positive impact on the site as a whole. Unless the perspectives of those who represent the diversity of the University’s student cohort are incorporated, validated, and respected, it is all too easy for vital information to slip through the cracks, far from the students who need it.

The problem with scaffolds – Christine Hindeleh

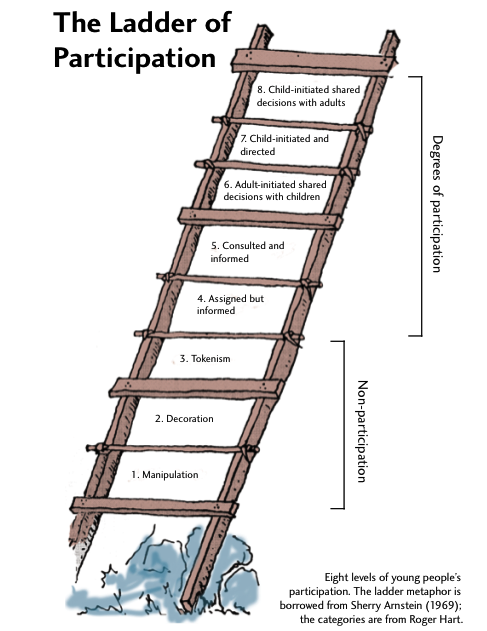

Using scaffolds for content creation and module review was a ‘necessary problem’ that shaped the development of Get Prepared. As useful as they are, they can also represent major barriers to student participation, framed by design intentions that narrow creative interpretation. In this way, they frame the distribution and sharing of power theorised in Roger Hart’s ‘Ladder of Participation’ (1997), which was developed in the context of early childhood education.

Using scaffolds for content creation and module review was a ‘necessary problem’ that shaped the development of Get Prepared. As useful as they are, they can also represent major barriers to student participation, framed by design intentions that narrow creative interpretation. In this way, they frame the distribution and sharing of power theorised in Roger Hart’s ‘Ladder of Participation’ (1997), which was developed in the context of early childhood education.

Using a ladder as a model, Hart describes how relationships between participation and power can be managed. The ascending rungs of the ladder represent increasing levels of agency, power, and control (increasing order of decision-making rather than a ranking of worst-to-best practice). The first three steps, (1) manipulation, (2) decoration and (3) tokenism, are examples of non-participation. The following five steps demonstrate active levels of participation, including (4) assigned but informed, (5) consulted and informed, (6) adult initiated, shared decisions with children, (7) child-initiated and directed, and (8) child-initiated, shared decisions with adults.

On Hart’s ladder, student co-designers working on Get Prepared most often worked on the sixth rung of participation, with educational designers providing initial ideas and frameworks that students then shaped in every step of the decision making process. As Robert mentions below, student co-designers were not required to decide on the topic of content creation, nor develop the site with a blank canvas. The site was already in a development stage when we were introduced to the project.

It is well established that scaffolds are needed to manage project development in projects such as Get Prepared. In this case, scaffolding allowed for valuable student perspectives to be balanced with academic expertise and completed in a timely manner.

The tension between the ideological thrust of co-design and its practical application nevertheless remains, and any teachers or academics looking to employ the process should take care in managing the obvious benefits of students’ voices alongside pragmatic institutional constraints (budgets, timelines, etc).

A key suggestion I have coming out of Get Prepared is that academic and professional staff interested in working with students as partners recruit student voices from the outset in scaffold design, giving them the chance to brainstorm before they create and review content.

Making it work online – Robert Tran

As phrases like ‘you’re on mute’ grow more familiar, it feels as if we’ve always been working online – communicating from our own little islands across the globe. We’ve also become familiar with the problem of not being adequately resourced to work or study from home with poor internet connections, an issue which particularly illuminates the experience of being a disadvantaged student. With that said, research shows that the academic performance of underrepresented student cohorts can be greatly enhanced by online innovations, making resources like Get Prepared all the more important.

Developing Get Prepared in the context of a global pandemic definitely presented its own challenges. Internet connections proved unstable, communications were not always clear, and the divisions between work and home were removed. As a team of student co-designers, we only met in-person once, to film a video introducing the site.

Challenges aside, every voice and opinion was heard as co-designers and members of the EI team worked collaboratively to design, create and review the site.

The success of this collaboration had a lot to do with the regular use of Zoom and the efficiency of sharing work on Google docs.

Aside from scheduled breaks allowing us to meet academic commitments, we held weekly Zoom meetings to discuss content and review tasks on a variety of topics, such as how to make connections in first-year, how to develop advanced-level study tips, and ways to gain professional purpose. While Zoom presented its usual challenges, such as how to use chat or knowing when to unmute at the precise moment to make the best contribution, the platform allowed us to connect without the restriction of a shared physical location. Living an hour away, this was particularly helpful for me, and even more so for members from regional and rural areas, to participate in group meetings.

Google Docs presented an all-in-one online software solution allowing the team to complete design tasks, read one another’s contributions, and leave comments on collective design principles. This opened a whole new world of collaboration, where multiple people could work simultaneously on different topics without disruption. Once each content creation task was complete, it was built into the relevant page in Canvas by the EI team from the ‘content creation’ Google Doc. The following week co-designers reviewed this content on Canvas, adding their suggestions to a ‘module review’ Google Doc.

Upon reflection, I would suggest other academic and professional staff interested in co-designing educational resources with students be mindful of organising content carefully on file-sharing resources like Google Drive to allow for a more streamlined, oriented approach. This, in theory, would take the strain off the individual’s capacity to manage their own contributions and shift it to a uniformly organised structure that all team members are familiar with.

Want to learn more?

We hope that this discussion will be something students, staff, families, and the broader community all find valuable, especially for future projects that amplify student voices.

For more on Get Prepared, check out the site on Canvas, or find out more about the site and suggestions that other students have about supporting the transition to university.

For more information on engaging students as partners, we recommend taking a quick look over the pedagogical research on peer-lead teaching projects.

We would also be grateful if you could support the Get Prepared site by circulating it amongst your peers, colleagues, teams and networks inside and beyond the university, especially if they are working with students transitioning to university, first-year students cohorts, first-year unit coordinators, or students from equity cohorts.