Why use marking rubrics?

Assessments are important educational tools, but they can cause confusion and stress if academic expectations are not clear. Some students may navigate university assignments through wider support networks and cultural capital. However, reliance on implicit understandings perpetuates disadvantage for students from non-traditional backgrounds who do not have access to these support structures. When assignment objectives are vague, students may resort to guesswork or mimicry, leading to work that lacks originality or academic integrity violations. This is not a good use of anyone’s time.

Assignment guidelines can help, but alone don’t clarify academic standards, which can vary greatly depending on the context and level of study. Even markers need support in understanding the specific criteria and standards and how it should be applied. Large units of study can be especially challenging since scale compounds the effect of bias. For example, a unit with 1000 students and 5 assessments requires a minimum of 5000 academic judgments; marker inconsistencies can compound and result in students receiving different grades as a result of something as arbitrary as the tutorial group they are allocated to. Unnecessary mark contests and formal appeals create surplus admin.

Rubrics do not eliminate these challenges entirely, indeed poor rubric design and implementation can exacerbate existing challenges by creating the illusion of rigor under the guise of a poorly written instrument. But designed carefully and integrated into teaching and learning through things such as marker calibrations, formative self-assessment, and approaches to assessment development and feedback they can provide a concrete tool by which to better clarify how our intended learning outcomes manifest within assignment specifics.

What is a Rubric?

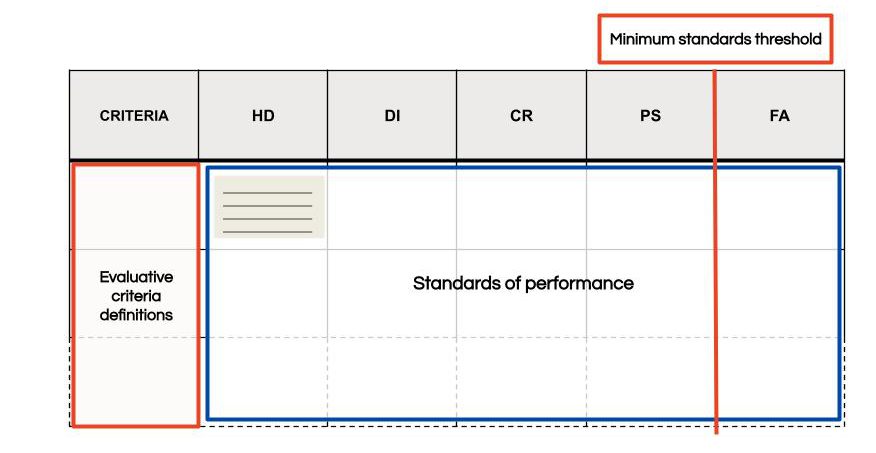

A rubric is a tool for communicating, discussing and marking assessments. It aims to make academic standards more explicit and can be used to guide students . This is usually presented in a table with:

- Evaluative criteria (what counts for that assessment): these can have different weightings to indicate importance and value.

- Quality definitions: descriptions for each qualitative level from maximum to minimum available marks or grade. For most coursework units at the University of Sydney follow the High Distinction, Distinction, Credit, Pass, and Fail grades outlined in the Coursework Procedures policy.

- Standards of performance: the individual descriptions of each evaluative criteria for each grade.

Crafting Your Rubric

Creating a rubric is a reflective process that begins with your Unit of Study’s Intended Learning Outcomes (ILOs) and Graduate Qualities (GQs). Here’s a step-by-step guide:

- Identify learning outcomes: Determine the key knowledge or skills you want your students to demonstrate. These should map to the unit learning outcomes or graduate qualities.

- Define and weight evaluative criteria: Decide on the core components of the assessment and how they should be judged. Consider the number of criteria required and the weighting given to each criterion.

- Establish ratings, scales, and numbers: Align the assignment rubric outcomes with common grade results, reducing the ambiguity caused by cross-scale translations.

- Assign numbers: Your assessment will be worth a percentage of the Unit of Study. Decide whether the marking will be out of a certain number of points, with each point reflecting a percentage, or out of 100 points but then re-weighted to determine the final mark.

- Write quality definitions: Define what each criterion looks like at each rating. Use clear language that students understand but don’t shy away from subject or discipline specific words.

- Descriptions should refer to observable and measurable standards. Consider the features that comprise the criterion.

- Standards should be reasonable and reflect the specifics of your teaching and learning context (e.g. introductory, first year, capstone etc.). Standards should not be so impossibly high that all students fail, nor so easy that the whole cohort is assessed to be exceptional.

- Think of quality definitions as a scale – work from the highest, lowest and minimum required standards for consistency in scale PS is the minimum standard required, HD is the best possible standard anticipated for that context and FA is a standard that is unacceptable. Once you define and describe these then the definitions of the grades in between (CR, DI) can be easier to write.

- Be precise and specific but not too granular this is higher education and you cannot hope to list every atomic part of each criterion or remove all academic judgement from the process.

- Use clear language that students understand but don’t be afraid of subject or discipline specific words this is part of the learning.

- Review, Refine, and Adjust: Take time to review your rubric and make necessary adjustments.

Embed your rubric into your teaching with staff, students and appropriate technology

A rubric is a tool that require interpretation, both between members of the teaching team and students. Rubrics can be embedded at several points in the assessment cycle. Give students access to the marking rubric alongside the assessment guidelines. Students can be involved in group or class calibration activities using exemplars and can even self or peer assess their own work prior to revising their final assessment and submitting this for the deadline. Rubrics should be part of calibration and initial marker meetings and can also be part of the feedback given to students. Tools like Canvas speedgrader and SRES can make the use of these to mark and calculate marks especially easy and reduce additional administration. Used this way, rubrics can be powerful tools in your teaching toolkit that help students and markers assess with greater clarity and shared understanding.

Resources and workshops:

- Review the resources available in this annotated document: https://bit.ly/Using-rubrics-23

- Draft your rubric using the following template: https://bit.ly/rubric-template-2023 (you can copy this in google docs or download this as a MS Word template)

- Register and attend an online rubric design workshop: