Asynchronous online learning is a key part of many degrees at Sydney, but one that students often struggle to engage with. Add in professional placement undertaken as a companion to the online study, in addition to regular university and life responsibilities, and it’s no surprise that Laura Di Michele wants to make this work as straightforward as possible for her MRSC5028 Clinical Radiography 3 students. Laura approached Educational Innovation to request an Educational Design Accelerator (EDA) project to work on optimising an online learning content developed to both support and complement the work her students do on their professional placements. Here we describe this work, offering some easily implementable suggestions to improve student engagement and content understanding, based on the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL).

About MRSC5028 Clinical Radiography 3

MRSC5028 is a placement unit, the third of four in the Masters of Diagnostic Radiography. In the June 2023 intensive 83 students in their second year for the degree took the unit. In each placement unit students learn skills for their professional practice and simultaneously work through coursework related to evidence-based practice. The coursework in Laura’s unit introduces them to the final steps of this evidence-based framework; implementation and evaluation. Undertaking coursework while on professional placement provides an immediate and authentic environment for students to apply their learning, and students gain maximum benefit from working through content at the same time. The placements, though, are not consistently timetabled; students can be rostered over regular workdays, on weekends, and overnight.

Design and development process

These inconsistent placement schedules presented a challenge for teaching MRSC5028, and so asynchronous online content delivery was the most practical option, and the one most respectful of students’ time. Laura wanted the module to be transformative to students’ practice as clinicians, for them to enjoy engaging with it and to imbue a sense of passion for translating knowledge into practice. She had already redesigned the unit’s assessments in line with these goals and sought out educational design expertise through the Educational Design Accelerator project to deliver the content that would support the completion of these assessments in a pedagogically sound and engaging way.

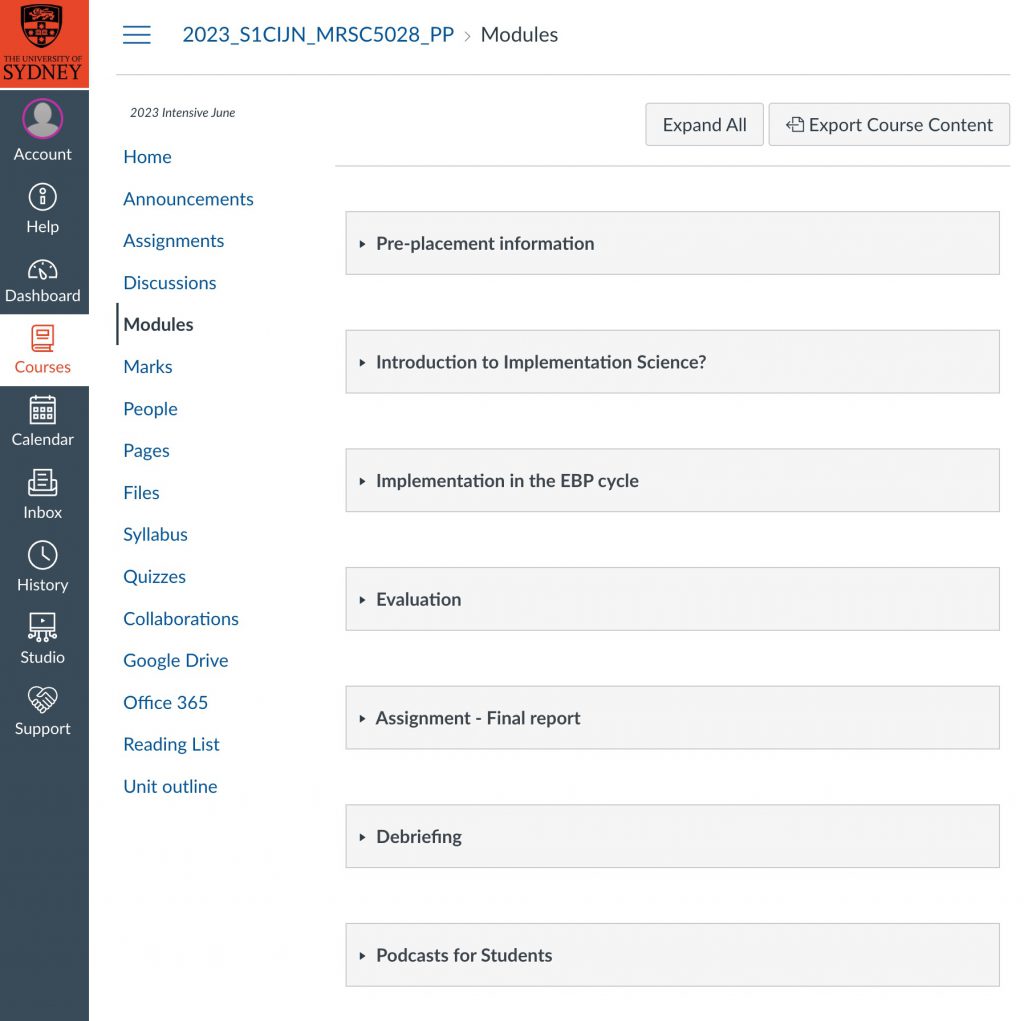

The project team started by reviewing the existing module design; a single large module in which information was delivered in a variety of ways to cater for diverse needs. Many Padlets were embedded to create interactivity and engagement with key knowledge and skills. After reviewing and meeting to discuss Laura’s aims, the project team settled on a few areas for further development:

- Developing a modular structure to support students working at their own pace

- Supporting students in actively working through the unit content, towards their final assignment

- Standardising site design and building consistency in content delivery

1 – A modular structure to support self-paced learning

Implementing a modular structure involves breaking down content into stages or steps. Depending on how modular structures are implemented, they can support students in understanding when and how to work through content, in returning to content for revision, in simplifying complexity, and/or in supporting the ‘narrative’ of your unit. There are also many features of Canvas that can support the communication of your vision to students. In MRSC5028 all the learning content was initially presented in a linear fashion within one module. A linear approach made sense here, as it does in most units of study, but a number of ‘stages’ were present that presented an easy solution to support understanding of which parts went together. The learning content was split into three stages; an introduction module to implementation science and its place in the evidence-based practice cycle, a module on the implementation framework, and another module on evaluation. These were complemented by other modules containing information about the student placement, the final assignment, and additional resources.

The structure implemented was designed to support, at a glance, students understanding the work required of them as they completed their placements. In addition, as all of the content presented was to be implemented in the final assignment, students could easily return to relevant stages when preparing their work for submission.

2 – Active learning, asynchronously

Active learning is incredibly important for student success, but implementing it in an asynchronous learning environment can be challenging. To help address this challenge, we looked towards our home-grown Student Relationship Engagement System, or SRES.

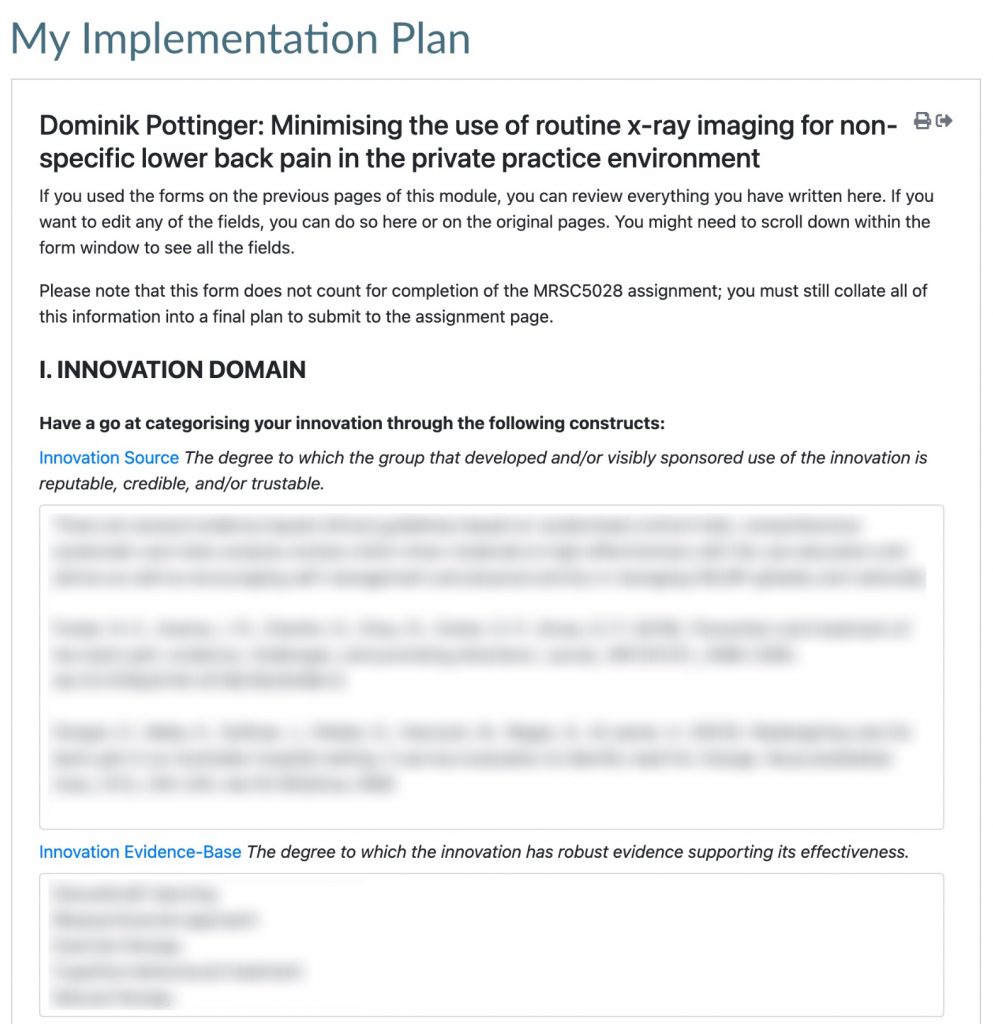

Our approach involved examining the content that students needed to engage with. For this unit, the content is based on the consolidated framework for implementation science. This framework supports practitioners in implementing their chosen innovation in a rigorous and scientifically valid way. Laura provided clear explanations of each aspect of the framework and emphasised its significance in professional practice. Within the unit, students were tasked with developing a final assessment outlining how they would apply this framework in a clinical setting.

Previously, Padlets had been embedded into Canvas pages to encourage students to consider each domain of the framework across the semester. Recognising the potential to align this work more directly with the final assessment, we identified an opportunity for students to actively and progressively construct their implementation plan throughout these pages. This was then easily consolidated into a single unified plan for students to use in the final assessment. SRES offered a straightforward method to achieve this. We embedded SRES forms on Canvas pages, prompting students to address each domain consideration step by step. Subsequently, all individual forms were compiled into a comprehensive implementation plan presented to students toward the end of the module.

Additionally, Laura used SRES to reach out to students midway through their placements, encouraging them to complete the forms if they hadn’t already done so. As a result, we observed that 80% of students engaged with and used this work for their final assessment.

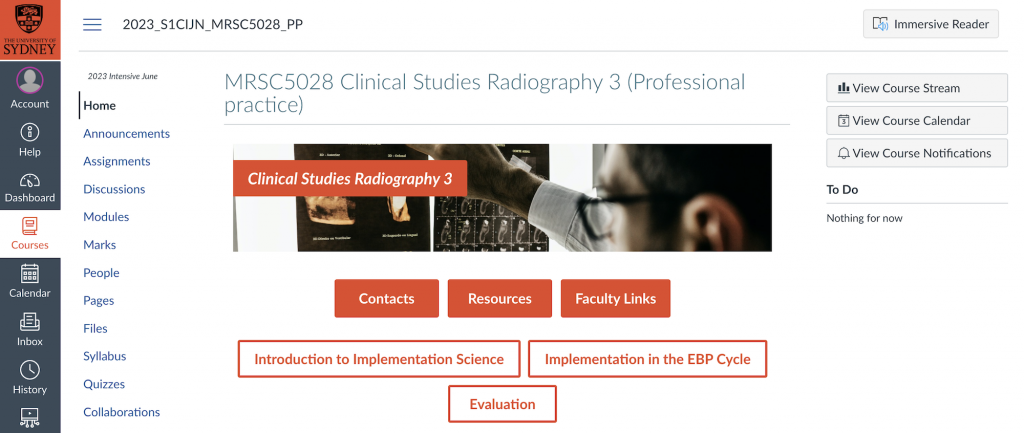

3 – Site and page design

A consistent visual identity builds a congruous experience for students, cuts down on mental load in navigating Canvas sites, and ensures that they are able to access important content and materials quickly and efficiently. Medicine and Health are currently in the process of developing these for all teaching areas based on simple principles, and we were able to use this project to roll out the first iteration of an identity for Medical Imaging Science (below). This design template’s homepage includes buttons that link to general and course-specific resources, a banner that will be seen across all medical imaging science units of study, a welcome message, a statement of learning design, and an Acknowledgement of Country.

Canvas pages were also re-designed for consistency and to best support student learning. Various visual elements were included, but the primary change implemented was to include learning goals for each module. In this instance, the learning goals are sub-goals of learning outcomes and are specifically related to mastery of the content and skills being presented in the modules. These learning goals communicate the intentions of the work to come and enable students to understand and communicate what they will have learned upon working through the content. Doing this builds self-sufficiency and executive function, encouraging students to directly link this work to the broader context of the unit; in this case their professional placement experience. Content accessibility was further improved by delivering it in a variety of forms, from formal readings, to videos, to explanations in simpler language. Videos were embedded directly into Canvas, and captions were added in all instances.

Laura’s initial design for the site included a large number of embedded Padlet boards. Many of these were converted into individualised forms for students (discussed in part 3), but some were retained. In deciding between individualising the activities or keeping them as Padlets we thought through the goal of the learning activity. Padlet is an asynchronous tool that, when set up as it was in this instance, facilitates anonymous posting of individual ideas in a communal space. In MRSC5028 it gave students a chance to anonymously share their ideas for using implementation science to receive feedback from Laura, who regularly checked the Padlet and commented on posts, but also to be inspired by other students. The work students did on Padlets could then be used for the completion of individual activities, outlined below, that were specifically designed to support the completion of their final assessment.

What’s next?

Since its launch the module has been adapted for a capstone unit of study in the adjacent Masters of Medical Imaging Science, and Laura has had interest in extending it into other allied health disciplines including Physiotherapy and Speech Pathology.

In terms of future development, additional evaluation mechanisms to the Unit of Study Survey were put in place to check in on how students specifically found the changes made, and Laura will use both of those and her own observations in order to decide on how to iterate further the next time the unit is offered. Laura reflected on the outcome of the process positively:

“I’ve been genuinely surprised and pleased with the quality of the (submitted work)… I even gave out my first ever full marks on an assignment in 8 years of teaching and marking! Given this is an entirely new concept that they’ve never been introduced to before the module I’ve been blown away”

The students of MRSC5028 generally rated the Canvas site as easy to work through and that it was easy to find specific information when returning to the site. They also thought that the asynchronous activities were easy to complete and helped them learn. One student specifically mentioned the collated implementation plan created using SRES, calling it “a great tool that can help us start to format our answers.”

USS feedback also indicated that there is an opportunity to offer further support to students who have questions about the unit content. To do this, in the future Laura will schedule drop-in sessions at different times of day to facilitate this within variable placement hours.

Find out more

- To hear more from Laura about the collaboration process, watch the recording of her presentation at the Sydney Teaching Symposium.

- Read about other recent Educational Design Accelerator projects.

- Unit coordinators and lecturers can request an Educational Design Accelerator project (note that these close during busy times of the year)