The disruption of higher education through forces such as technological innovation, globalisation, shifts in government funding, and changes in the nature of work has long been predicted. Just as music downloads and ride-sharing transformed the music and taxi industries forever, MOOCs and private providers have been seen by some as taking over from traditional universities. So far, the “end of the university as we know it” hasn’t happened – but is all fine? In Australia, at least, the university sector is in a period of expansion with considerable investment in infrastructure both on the traditional campuses and overseas.

In her keynote “Re-imagining Higher Education for the Anthropocene” at HERDSA2019, Jane Gilbert argued that higher education is at a tipping point where most effort is currently being directed to tinkering with the current models and very few are thinking about a pending paradigm shift in the delivery, structure, and purpose of higher education. The choices that all those who work in higher education make will be critical in determining its future, its shape, and its purpose.

The digital revolution and the future of work

With computing power continuing to increase, Prof Gilbert argued that information technology will affect and disrupt everything in the near future. Technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics will radically alter manufacturing, science, engineering, and medicine. The rise in computing power is such that “the singularity is near“: the point at which machine intelligence is greater than human intelligence. With no professions unaffected, if the purpose of higher education is preparing students for employment then it clearly must change.

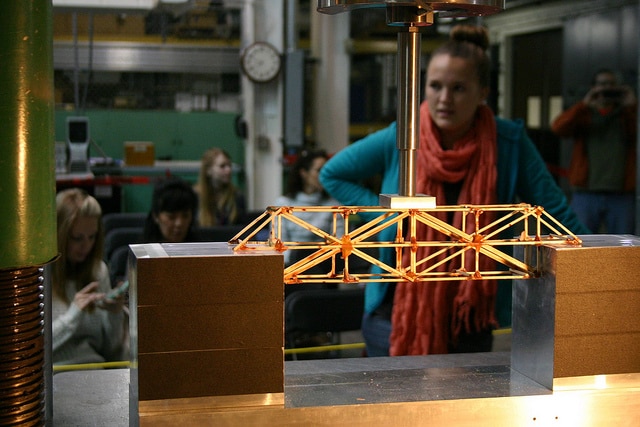

AI will alter the way students are taught through smart and adaptive tutoring systems. Research will also be conducted in new ways with automation and machine learning potentially replacing the laboratory researcher and the social scientist. In my own discipline of Chemistry, it is not hard to imagine computers and robots designing and synthesising new materials and medicines and fully automated analyses. With their ability to work 24 hours a day and to conduct multiple reactions in parallel, it is easy to see technology leading to us hanging up our lab coats in the very near future.

With no work to do, humans will be free to pursue other activities and interests unrelated to career aspirations

If the future of work is that humans do very little of it, the economy will need to be managed for full unemployment. Whilst new jobs may be generated, as has happened after other disruptive changes such as the industrial revolution, in this scenario the purpose of the university is very different. With no work to do, humans will be free to pursue other activities and interests unrelated to career aspirations.

The Anthropocene

Some argue that we are now in “The Anthropocene“, an epoch in which human activity is the dominant force affecting the Earth’s physical processes, geology, and ecosystems. Anthropogenic climate change, for example, is already having major implications for natural ecosystems, agriculture, and all aspects of human life. Many disciplines were forged and formed in past eras such as the Enlightenment and the industrial revolution. In the Anthropocene, the purpose and nature of these disciplines in education and in research will be different and new ways of thinking are needed. Bruno Latour, for example, has argued that we are now deeply entangled with nature and hence science and scientists are not separate from the things that they study. Instead, scientists need tools to study these entanglements.

Re-imagining higher education for the post-singularity, post-work Anthropocene age

Given the size and nature of these shifts, Prof Gilbert suggested that a paradigm shift is already overdue. Whilst throwing everything out and starting over is unlikely given the history and size of the sector, just tweaking our current approaches to education and research is an insufficient response. Rather, it is everyone’s responsibility to think, engage, and act differently and using ideas from the past and future. As Riel Miller suggests, we all create the future every day and need to be “future literate” in the choices and actions we take. In place of teaching students ways to reproduce existing knowledge and ways of thinking in order to build new knowledge in the existing disciplines, a future-focussed education needs to think between and beyond these disciplines. Tackling “wicked problems” such as food and water security, antibiotic resistance, and population growth requires expertise across multiple disciplines and an openness to collaboration inside the university and outside our traditional partners. For educators, it requires a renewed focus on innovation, creativity and critical thought and an understanding that none of these are the sole domain of individual disciplines.