Learning through practice is a foundational and essential part of the student experience (Laurillard 2012). Giving students the opportunity to attempt tasks, make mistakes, process why they made mistakes, and then adjust their future approaches accordingly is important (Connell et al. 2017). It helps students acknowledge their misconceptions and helps teaching staff identify content areas that are particularly challenging for students, possibly due to lack of exposure from their prior learning (Wood 2009). Learning through practice forms part of an evidence-based approach to teaching and curriculum development, which is student-centred by nature and facilitates an iterative improvement process (Merkel 2016).

This article was contributed by Balwant Singh and Tom Jephcott.

SOIL2005 (Soil and Water: Earth’s Life Support Systems) is a small (~ 60 students) second year unit of study that was introduced in 2018 with the revised curriculum at the University of Sydney. Prior to 2018, introductory soil and hydrology contents were taught into two separate units of study, targeting soil science (SOIL2003) and hydrology (LWSC2002), respectively. The unit merger presented two main challenges, (i) delivering adequate introductory contents in relation to soil and water, and (ii) ensuring the content was well integrated. Such teaching challenges associated with major curricular revision are not unprecedented but often underestimated (Pock et al. 2019). The unit of study survey (USS) scores and comments after the first-year session in 2018 reflected this challenge, with an average USS score of 2.92 / 5.0 across eight question items. Students were particularly critical about the organisation of the unit, the Canvas site and resources, and the integration of different topics.

In response to this feedback, the unit of study coordinator, Professor Balwant Singh in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences contacted me, an educational designer in the Faculty of Science Education Portfolio, to initiate a review of the unit design with the view to improving the student experience. The academic staff considered some changes to the contents and sequences of the unit of study. Additionally, simple measures were considered, such as improvements to the Canvas site design and module scheduling, and more significantly, ensuring that all students were continuously engaged and provided opportunities for learning through practice.

From little things…

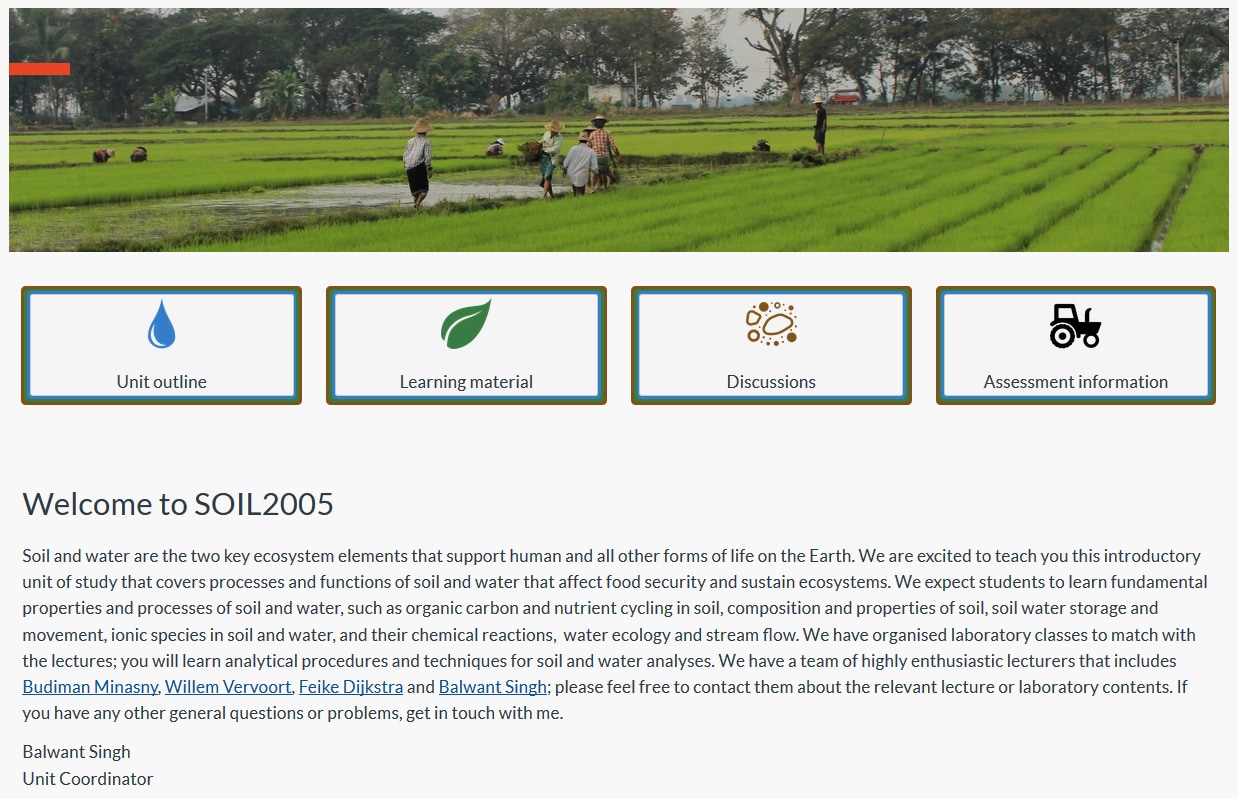

Figure 1: The landing page of SOIL2005 for the 2019 teaching session. Four core links were provided to students, taking them to the unit outline, the modules (learning material), the discussions (Canvas discussions), and the assessment information (dedicated page). Teaching staff names were linked to their emails, allowing students to quickly reach out.

Simple changes to the Canvas site were the first point of order; new buttons and icons were built to invite students to explore key resource areas (Fig. 1). The modules were reformatted in a weekly structure and were released progressively to students as the semester progressed. The structure of the modules was also revised, with dedicated sections for lectures, practicals, and revision contained within each module. A dedicated staff contact page was built which presented staff contact details and introductions to students. Finally, a dedicated assignment page was built which presented assignment weightings, timings, learning outcomes, and links to submission drop boxes. Now that the Canvas site was in order, it was time to think about how students were interacting with and revising the content as each week progressed.

Regular watering

It was hypothesised that if students were completing a revision quiz each week on that week’s content, their results could form the basis of discussions to address knowledge gaps in the ensuing week. The lecturers would be able to use the quiz results to identify the areas that were particularly challenging for students. If this was combined with automatic feedback delivered to the students based on their answers to the questions, we would hopefully be providing a means of helping students link the different content areas of the unit, at a point in time that was directly useful to them in planning for their assessment tasks (Wiliam 2010). However, the key to this measure having impact was student participation in weekly quizzes. With insufficient time to include a summative component in the quizzes (Palmer and Devitt 2014), we decided to use module requirements and prerequisites to guarantee participation. This meant that each week’s revision quiz was a requirement to satisfy completion of that week’s module, and access to each week’s module was dependent on completion of the previous week’s module. Thus, for a student who wanted to access the week (n) module material she/he would first have to complete the week (n – 1) revision quiz. Not only were students exposed to regular formative assessment and feedback but results from the quizzes were integrated into lecture discussions.

Professor Singh explains:

“The results of weekly quizzes were discussed as a follow-up. The results for questions were displayed in lectures, with a brief discussion about the answers, particularly where a majority of students have given wrong replies.”

Growth spurt

Table 1: SOIL2005 grade proportions for the 2018 and 2019 teaching sessions, including absent fails (AF), fails (FA), passes (PS), credits (CR), distinctions (DI), and high distinctions (HD). Increases in the proportion of credits, distinctions and high distinctions, and decreases in the failure rate, were encouraging.

| student_n | AF_% | FA_% | PS_% | CR_% | DI_% | HD_% | total_pass_% | year |

| 57 | 0.04 | 0.21 | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.12 | 0.04 | 0.72 | 2018 |

| 61 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.34 | 0.30 | 0.15 | 0.08 | 0.87 | 2019 |

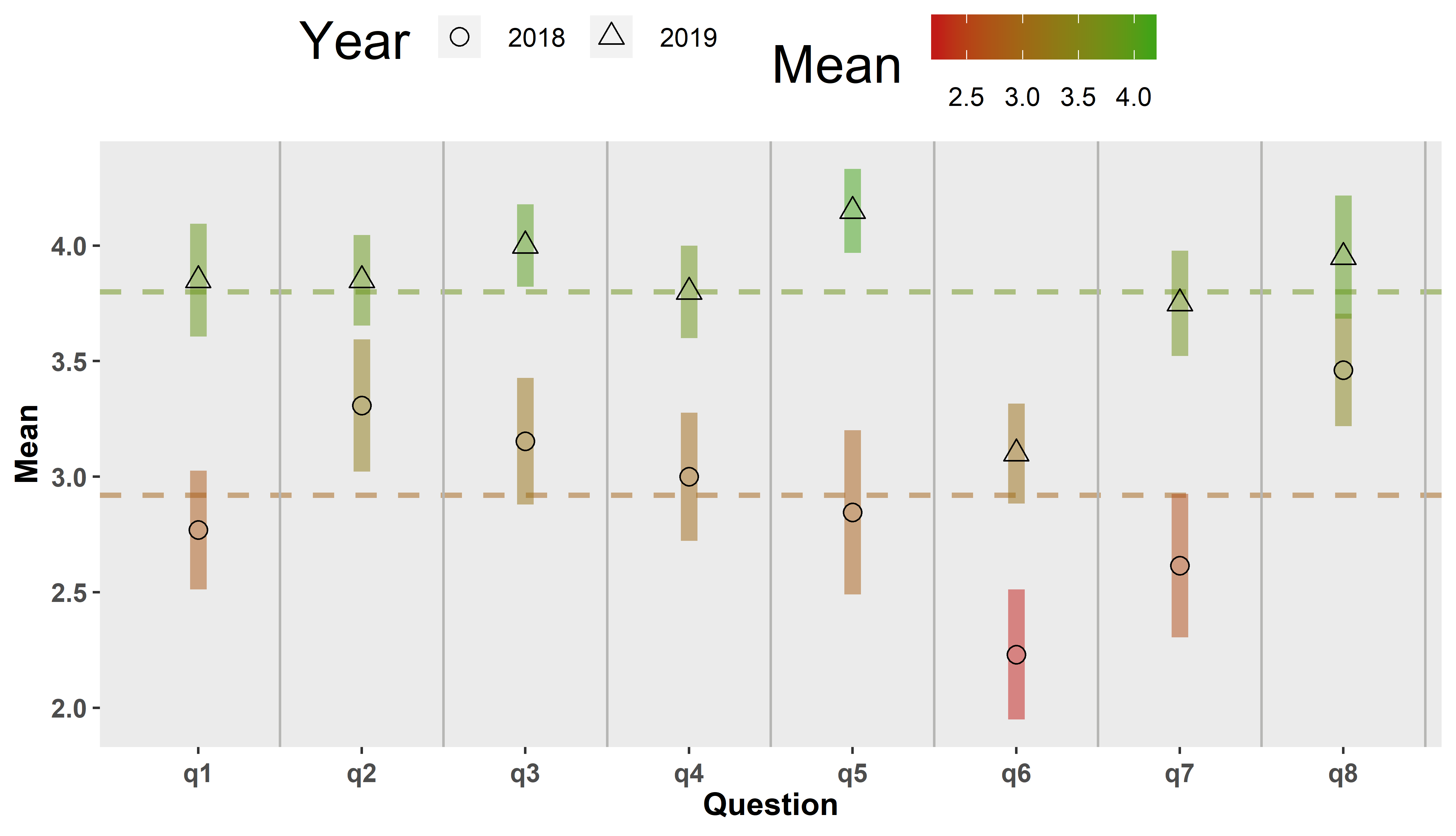

Figure 2: ANOVA means for each question item (± standard error), colour coded according to an automatic scale, and at each teaching session year. The overall means for each year are presented as dashed horizontal lines. Significant differences between the year (p < 0.001) and question (p < 0.05) were found. The questions relate to quality of teaching (q1), intellectually rewarding work (q2), developing critical thinking skills (q3), access to valuable learning resources (q4), challenging assessments that helped learning (q5), helpful feedback (q6), clear links between assessments and unit learning outcomes (q7), and relevant content based on degree requirements (q8).

The comparison of USS results between the 2018 and 2019 teaching sessions was encouraging; students performed better in the 2019 session compared to the 2018 session (Table 1). The unit achieved significantly higher scores in all question items, with particular improvements noted in Q5 (The assessment tasks challenged me to learn), and Q7 (The assessment was clearly linked to unit learning outcomes) (Fig. 2). In their qualitative survey comments, several students specifically identified the quizzes as having helped foster their understanding of the content. One student, who mentioned the quizzes favourably, also expressed that the quizzes should not be compulsory. The student felt that compulsory completion of the quizzes led to hastily completing the questions in order to access the material for next week without making genuine attempts at the questions. Despite this, it was pleasing that students recognised the value of regular revision opportunities provided to them by the weekly quizzes.

Of value to the teaching team was an insight into topics students were finding particularly challenging, and opportunities to address these challenges before students were confronted with summative work. The quizzes allowed the teaching team to identify areas, such as questions involving calculations, and questions addressing soil physics concepts.

Next season

Balwant and I had many ideas for change in the unit of study before the 2019 teaching session, however time constraints prevented us from implementing all of them, and the performance of the unit and effectiveness of the changes we made will inform the teaching approach taken in the 2020 session, as Professor Singh outlines:

“Next year, I am thinking of using a lecture slot in the final week of the semester to go over the results of all quizzes. The lecture will be used to clarify any confusion in understanding a concept and / or calculations needed for a question.”

In addition to these changes, we will critically review how we communicate the requirements of the assessments to students, as this was a point of mixed reception in the feedback. We also hope to make more use of Canvas rubrics for assessment marking and feedback delivery and closely examine our formative quiz questions to ensure they are targeting a diverse and appropriate array of cognitive levels. Finally, we would like to more deliberately target laboratory learning outcomes with our formative quizzes; dedicated laboratory quizzes were developed for the last three practical sessions, but not for the earlier sessions, and this potentially represents an unaddressed area for students. Despite the evident improvements of the unit, feedback is still the lowest scoring item and is sitting well below the unit average for 2019; clearly this needs attention.

In summary, we were delighted at the improvements that the unit has achieved between the two teaching sessions and are particularly excited at the demonstrated power of student engagement with regular formative assessments. These results will inform the future development of the unit, through which we hope to further improve the student experience and outcomes.

References

Connell GL, Donvan DA, Chambers TG (2016) Increasing the use of student-centred pedagogies from moderate to high improves student learning and attitudes about biology. CBE – Life Sciences Education 15, 1, ar3.

Merkel SM (2016) American Society for Microbiology resources in support of an evidence-based approach to teaching microbiology. FEMS Microbiology Letters 363, 16, fnw172.

Laurillard (2012) Teaching as a Design Science – Building Pedagogical Patterns for Learning and Technology. Chapter 11 – Learning Through Collaboration pp. 162 – 186. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group, New York and London.

Palmer E, Devitt P (2014) The assessment of a structured online formative assessment program: a randomised control trial. BMC Medical Education 14, 8.

Pock AR, Durning SJ, Gilliland WR, Pangaro LN (2019) Post-Carnegie II curricular reform: a North American survey of emerging trends & challenges. BMC Medical Education 19, 260.

Wiliam D (2010) The role of formative assessment in effective learning environments. In Dumont H, Istance D, and Benavides F (Eds.) The nature of learning: Using research to inspire practice (135 – 159). OECD Publishing.

Wood WB (2009) Innovations in teaching undergraduate biology and why we need them. Annual Review of Cell and Developmental Biology 25, 93 – 112.