Many pharmacy students will find themselves working in diverse clinical contexts where cultural competence and effective inter-cultural communication is essential for optimising patient care and addressing racial disparities in health. While the rationale for developing pharmacy students’ cultural competence within the pharmacy curriculum is clear, its relevance may not be immediately obvious to incoming first-year pharmacy students. Traditional teaching methods rely on self-reflection, lecture, diversity service-learning, case studies and discussion. These didactic approaches help to operationalise cultural competence but the challenge remains where students have difficulty grasping the nuances of cultural competence and applying it in a healthcare context. Many find the concept of cultural competency abstract and difficult to grasp at first and is sometimes met with resistance. As an educator, I am often asked by students: what does it mean to be culturally competent? How do I know if I’m being culturally competent?

Teaching context

In 2023, the Sydney Pharmacy School started implementing its virtually integrated curriculum, providing the perfect opportunity to rethink the curriculum and integrate new ways of teaching and introducing cultural competence to first-year students enrolled in Pharmaceutics and Pharmacy Practice (PHAR1921). Prior research has shown the benefits of taking students outside of the clinical environment to learn about implicit biases in medicine. Similarly, students in PHAR1921 may also benefit from taking their learning outside of a clinical setting, while removing the need for pre-requisite clinical knowledge to help students access concepts of culture and health.

Education design

In consultation with the Academic Engagement Program team at the Chau Chak Wing Museum, an Object-Based Learning (OBL) workshop was designed, capitalising on the extensive range of historic health artefacts that form part of its diverse collection. The strength of OBL lies not only in interrogating the curated artefacts, artworks, and specimens but also in what these objects represent to the beholder: triggering memories, emotions, forming new connections and generating new ideas. In the 2 hour workshop, students worked in small teams of 5-6 people across three scaffolded activities designed and facilitated by the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s Academic Engagement Curators. Key learning objectives were to develop student’s awareness of different knowledge systems across cultures and time periods, the connection between beliefs and health, as well as how health messages are framed and can be interpreted by different audiences.

Activity 1: Museum “hunt” and the Ambassadors exhibition

In the first activity, students used an interactive team-building museum hunt app to explore the exhibition Ambassadors, which is distributed throughout the museum. Students located relevant artefacts and responded to questions and prompts (written, photographic, and video responses) about each of the First Nations Ambassadors exhibited in the museum.

Activity 2: Analysis of objects and communication

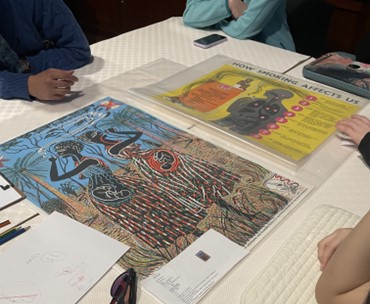

In the second activity, each team was given two historic health posters bearing infographics. These included posters from Australia and Papua New Guinea in the 1960s-1990s and were selected in order to include a broad range of culturally and linguistically diverse audiences, including First Nations Peoples. Students started with ‘deep looking’ at each infographic, observing the design elements, including colours, symbols, images, text, design, and composition. As a team, students made inferences about the underlying health message, the intended audience and who commissioned/designed the infographic. They then compared the two posters commenting on the communication elements that were effective/ineffective in each. This exercise stimulated rich class discussions about stereotypes, cultural appropriation, and historic social norms about health and culture especially when looking at the artworks through a modern lens of diversity and inclusivity.

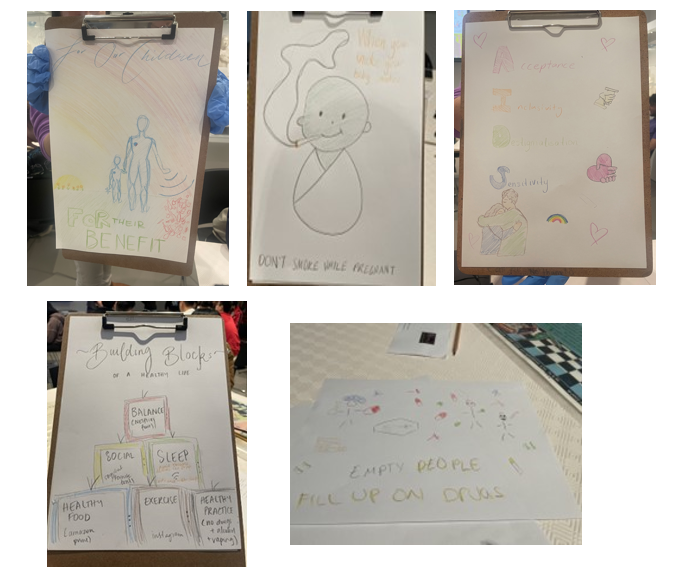

Building from the initial discussion, each team was then tasked with re-designing the health infographic, to communicate the same health message to a contemporary audience. Students then presented their infographic to the class, explaining the message they wanted to convey and to whom and why they chose to depict the message in a particular way. This creative process enabled students to reflect on their own experiences and the need to frame the health message to the broader Australian population. In this creative task, students carefully selected colours, words and illustrated symbols that would render the new infographic more effective. The juxtaposition of health messaging was intentional and is grounded by one of the 12 strategies recommended by Martinez and colleagues (2015) for teaching students about social determinants of health. The goal was to bring to light the history of racism and health disparities in a health context and the corrective actions of modern-day practice. Importantly, the creative re-design process also empowered students to be agents of change and advocacy, instilling principles of social accountability early in their professional careers.

Activity 3: Communicating to diverse audiences

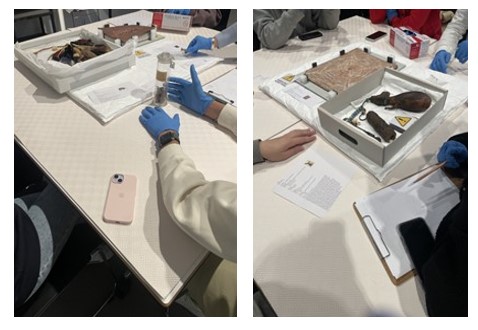

Each team was then allocated two objects from the museum collection, all of which were related to health care. For example, these included botanical specimens with links to healthcare across different cultures, Ancient Egyptian amulets used to protect the wearer from illness and misadventure, and Indigenous bark paintings that show the integration of healthcare in different ecosystems. Starting with ‘deep looking’, students made observations about the object’s shape, size, and colour before making inferences about its use and origins. From this initial exercise, each team was asked to pick one object and to think of ways to effectively communicate the object to two very different audiences (e.g. kindergarten students vs university academics; international diplomats vs First Nations People; people with low vision vs high school students). This exercise emphasised the importance of considering the audience when communicating information. It allowed students to practice the skill of moderating their method(s) of communication (e.g. written text, YouTube video, podcast, image), their choice of wording and tone and which aspects of the object they would emphasise (e.g. function, role in society, historical narrative) for each target audience.

Reflection

At the start of semester, I had reservations about tasking my first-year students with a group assignment involving the development of a health infographic on a simple ailment for a culturally and linguistically diverse population. Was it too much of a task to ask for? How do I explain the framing of a health message to first-year students? Through the various active learning exercises and interaction with the collection items, students were able to organically make tangible connections with abstract concepts around culture, health, and communication. Importantly, the activities in the OBL workshop allowed students to share and observe the diversity of perspectives that each team member brings to the table, providing a team-building opportunity prior to working together. So far, the feedback for the workshop has been overwhelmingly positive.

I enjoyed that session a lot, as I felt more engaged.

It was helpful to understand cultural diversity.

Want to know more?

Get in touch with the Academic Engagement Curators at the Chau Chak Wing Museum: [email protected].

References

Davis, M. (2020). The “Culture” in Cultural Competence. In J. Frawley, G. Russell, & J. Sherwood (Eds.), Cultural Competence and the Higher Education Sector: Australian Perspectives, Policies and Practice (pp. 15-29). Singapore: Springer Singapore.

Haack, S., & Phillips, C. (2012). Teaching cultural competency through a pharmacy skills and applications course series. Am J Pharm Educ, 76(2), 27. doi:10.5688/ajpe76227

Martinez, I. L., Artze-Vega, I., Wells, A. L., Mora, J. C., & Gillis, M. (2015). Twelve tips for teaching social determinants of health in medicine. Medical Teacher, 37(7), 647-652. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2014.975191

Micheal, S., Ogbeide, A. E., Arora, A., Alford, S., Firdaus, R., Lim, D., & Dune, T. (2021). Exploring Tertiary Health Science Student Willingness or Resistance to Cultural Competency and Safety Pedagogy. Int J Environ Res Public Health, 18(17). doi:10.3390/ijerph18179184

Zeidan, A., Tiballi, A., Woodward, M., & Di Bartolo, I. M. (2019). Targeting Implicit Bias in Medicine: Lessons from Art and Archaeology. West J Emerg Med, 21(1), 1-3. doi:10.5811/westjem.2019.9.44041