In Semester 1, 2020, I coordinated the postgraduate research capstone unit in the Master of Economics (MEc) program – Economics Research Project (ECON7030). The key requirement of the unit is the writing and completion of a 6,000-word research report. The unit places emphasis on students acquiring skills in independent research using the knowledge they have mastered in the MEc program. Regular workshops and meetings with the instructor(s) are critical to successful completion of the individual research projects. As I was enthusiastically preparing to embark on this four-month-long research journey with my students, the world was hit by COVID-19. The rapid transition to online teaching left students, especially international students, in a state of utter confusion. They panicked, not knowing how to proceed with an independent research project without any face-to-face contact and support. Given the tight deadlines, it was important for the students that they identified feasibility issues in their research plan and rectified them early enough to allow for a timely submission.

Desperate times often motivate us to adopt tools and techniques which have always been out there but not been explored, at least not consciously. And this is how I came upon my strategy to deal with the challenge that confronted us without any warning – I decided to use the power of feedforward in achieving timely and efficient completion of the projects. As opposed to feedback that looks back at work that has been done, feedforward is ‘future-oriented’ (Sadler, 2010), focusing on how students can improve. Many sources of student dissatisfaction with feedback revolve around the timing of feedback (Wimhurst and Manning, 2013). Feedforward refers to ‘timely and constructive feedback’ that feeds into the next assignment (Hounsell et al., 2008). Hence, the literature often connects it to self-directed learning. The approach is rooted in traditional theories of learning, for example, Kolb’s learning cycle (Kolb, 1984). Diverse practices or interventions are labelled as feedforward: instructor’s written comments on student work, or activities engaging students with exemplars and assessment criteria/rubrics. Some researchers (Vardi, 2013) propose carefully designed staged activities which are expected to result in measured improvements (e.g. measured by grades) in subsequent tasks. I adopted a combination of the above approaches.

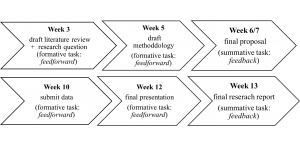

I primarily focused on feedback plus feedforward via formative assessment. Students were offered feedback on draft assignments (created in Canvas) before they submitted the final version of the assignment which allowed them to incorporate my suggestions in the final version (summative task). Following the timeline described below, by the time students reached the stage of writing the final report, a significant fraction of the work was already commented-upon and completed.

- Week 3 – Draft literature review and research question (formative task; feedforward)

- Week 5 – Draft methodology (formative task; feedforward)

- Week 6/7 – Final proposal (summative task; feedback)

- Week 10 – Submit data (formative task; feedforward)

- Week 12 – Final presentation (formative task; feedforward)

- Week 13 – Final research report (summative task; feedback)

More formally, the steps that I implemented are:

- Preparation:

- A marking rubric setting expectations about the task

- Guidelines and clear explanation of tasks

- A tentative timeline of tasks

- Exemplars

- Formative tasks and pre-assessment feedback

- Two draft Canvas assignments in the first six weeks – (i) draft literature review which would lead to a research question, and (ii) draft methodology outlining the source of data and potential modelling approach. The written proposal was due in week 6 by which time they have already received feedback on the draft.

- Submitting research data in weeks 9/10 and receiving feedback on any concern with the quality or suitability of data.

- A final presentation in week 12 (formative task) where they received detailed feedback on the content, ahead of the actual submission of the final research report in week 13.

- Weekly meetings in Zoom scheduled via Canvas Calendar to discuss feedback comments on student submissions and clarify doubts and respond to queries.

- Regular email communication via Student Relationship Engagement System (SRES) & Ed, at the beginning of every week with updates, reminders on the week’s tasks, and logistical details.

Upon reflection, my strategy was not without its flaws. Some students did not like the idea of having to undertake so many Canvas submissions (formative plus summative tasks). Besides, the literature is not united on the efficacy of rubrics or exemplars (Wimhurst & Manning, 2013). However, the net outcome was positive in the context of my unit as evidenced by multiple comments on ‘helpful feedback’ in the USS evaluation report (USS score on ‘helpful feedback’: 4.4). The most likely channel via which the positive effect of feedforward was transmitted is reduced student anxiety, which is a proven obstacle to deep learning (Entwistle & Ramsden, 1985) particularly in economics (Chew & Cerbin, 2021).

In my context, a reasonable class size (51 students) probably helped to implement the strategy in the way I did. Large units comprising hundred plus students, may have to adopt a different approach to effectively integrate feedforward into learning activities – for example, setting small weekly tasks and using the support of tutors. Brainstorming on the right approach will be a worthwhile exercise. Investing time and resources on exploiting the power of feedback plus feedforward is likely to have large payoffs in the long run in the form of improved student outcomes.

References

- Chew, S. L., & Cerbin, W. J. (2021). The cognitive challenges of effective teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2020.1845266.

- Duncan, N. (2007). “Feed-forward”: improving students’ use of tutors’ comments. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 32(3), 271–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930600896498

- Entwistle, N., & Ramsden, P. (1983). Understanding Student Learning (Routledge Revivals). London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315718637

- Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research and Development, 27(1), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360701658765

- Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning : experience as the source of learning and development . Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hal

- Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535–550. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930903541015

- Vardi, I. (2013). Effectively feeding forward from one written assessment task to the next. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(5), 599–610. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2012.670197

- Wimshurst, K., & Manning, M. (2013). Feed-forward assessment, exemplars and peer marking: evidence of efficacy. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 38(4), 451–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2011.64623.

2 Comments