When you think of ancient memory devices you might think of a memory palace. This is a memory device used by memory champions to recall, quickly, a set of shuffled cards in sequence. It was a technique used by Roman orators who would imaginatively assign a piece of their speech into a physical building they knew well, such as their home. When they recited the speech, they would imaginatively move through their home retrieving the part of the speech assigned there as they performed. The part of the speech, or whatever you need to remember, can be represented as a person, animal, goddess, or any animated being, interacting with the space in an amusing or surprising manner. The more vivid the image, the easier it is to recall. Information combined with emotion moves to long-term memory. We remember stories more easily than dry facts.

Our natural memory stores information randomly which makes it difficult to retrieve. Allocating information to a filing system makes it easy to retrieve. That is the principle of using memory palaces: it trains our memories.

There are many more ancient memory devices that we can use and encourage our students to use. We can call these mnemonic technologies. These were taught in ancient times, in the medieval period and the Renaissance. We can consider resurrecting their use to help students today.

Orality

Imagine you live in an ancient oral culture. Try not to think about oral cultures as lacking literacy but as fully functioning rich cultures; they didn’t know they lack literacy.

How does your tribe communicate important information? How is the knowledge of the tribe, knowledge about how to live, how to hunt for food, how and when to trade with other tribes, how to resolve problems, how to perform rituals to honour life events, genealogies, taxonomies of plants and animals, pharmacopoeia and timekeeping, how to navigate across deserts or oceans, how is the information communicated? How is it passed down from one generation to the next?

This knowledge may be embedded in memory devices which might be physical, like rock paintings, statues, totems, decorative art on masks or bowls, it could be told through dance and song, or might be related orally through language and stories. They created storage devices for information with layers of information, indexed and retrievable, taught in layers upon layers in a structured manner to each new generation. Knowledge was secret and protected, restricted to the initiated.

Let’s think about the range of ancient memory devices and then consider how we can use them to help our students learn.

We might categorise these mnemonic technologies as different types of encoding or inscribing information: through language, through performing arts, on small objects, and in our environment. A leader in this field is Lynne Kelly, Australia’s Senior Memory Champion, who has documented her 40 memory experiments and writes that Indigenous knowledge was embedded in a concrete reality.

Encoding in Language

All the sayings or slogans or quotes that you remember are memorable by design. In an oral culture, this could mean the difference between life and death. For example:

- Red sky at night, sailor’s delight. Red sky in morning, sailor’s warning.

- Look before you leap.

- A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.

- Forewarned is forearmed.

- A light purse makes for a heavy heart.

- Fail to plan, plan to fail.

You will notice some literary techniques used here: short sentences of monosyllabic words, alliteration, repetition, parallel constructions, use of opposites, epithets, rhythm and rhyme.

All the literary terms you learned in primary school are memory devices. Ancient oral memory devices became our literary devices, according to Walter J. Ong, who wrote Orality and Literacy: The Technologizing of the Word in 1982.

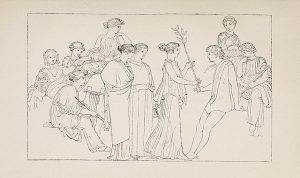

Mnemonics are memory devices. The word mnemonics is based on the ancient Greek word for memory. The Greek goddess of memory was Mnemosyne, daughter of Gaea (Earth) and Uranus (Sky), mother of Zeus and the Muses. These are personifications or anthropomorphosis or symbols of physical realities and concepts. A mnemonic for spelling ‘mnemonic’ is “Memory Needs Every Method Of Nurturing Its Capacity”. The memory devices, including acronyms, are types of mnemonics.

We naturally remember events and situations that we respond to with strong emotions or that are surprising or have meaning for us. We remember stories because distinctive characters doing surprising things create a vivid mental image and have an emotional impact. Scholars now theorise that the ancient mythology of Homer, which was epic oral poetry, could be stories based on memory devices, wherein distinctive and lively characters interact with each other. For ancient mythological stories, we remember the stories but not what they meant for ancient people. Eventually, we tell the stories (mythologies) rather than knowing the material things to be remembered. Future generations may believe it was important for us that “every good boy deserves fruit”, rather than what it is a memory device for, that is, musical notation. The clarity around what is literal and what is figurative has disappeared for us but would have been clear for people initiated in the knowledge. Epic poets like Homer, who was thought to be blind, memorised up to 15,000 lines which were recited over several days of performance. This is evidence of a trained memory.

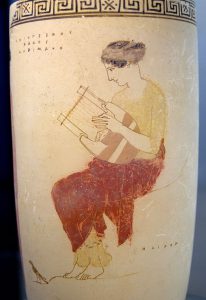

Encoding in the performing arts

The use of song, dance, rhythmic music, chanting, or anything performed and repeated in rituals and ceremonies, were ancient memory devices. Examples in teaching include singing the alphabet song whist pointing to letters with corresponding pictures and chanting the multiplication tables. We could expand on these from primary school uses to be more creative.

By asking students to create memory devices we are asking them to shift modality to express their understanding of course content.

They need to synthesise their knowledge. It is a good method of assessing understanding and creates memorable learning experiences which are shared amongst class members. The more active and embedded in the body the stronger the memory. Remember, Mnemosyne was mother to the nine muses who inspire the creative and performing arts. It is hard to imagine a more concise and elegant expression that memory belongs with the arts than this relationship of lineage.

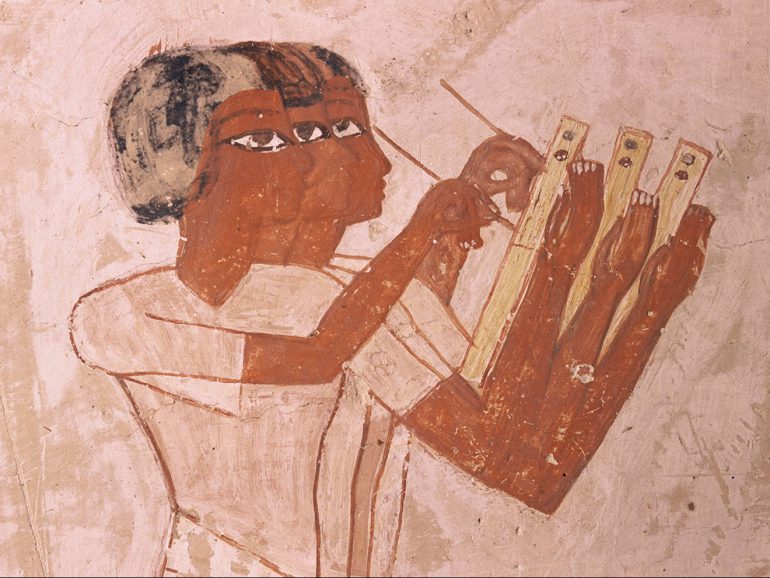

Encoding in small objects

Knowledge may be embedded in memory devices which might be physical, like statues, totems, or decorative art on garments, masks, Winter Counts (pictographs to mark the year), lukasa (memory boards), Khipu or Quipu (knotted strings), bowls or strings of beads. These might be felt by touch or they might be visual prompts. For example, Aboriginal dot paintings are maps, even though we may not have recognised them as such. In oral cultures, art is the presentation or materialisation of culture.

Encoding in our environment

The same principle applies to larger expanded natural or built environments as touchstones for memory.

Stonehenge could be a memory device around which rituals were performed. These rocks could have been erected to replicate the homeplace of a tribe who moved to another region and brought the implements on which they had inscribed their knowledge. It would be like moving a library. Lynne Kelly lists the ten indicators of a memory site here.

Australian Aboriginal people embedded memory in landscape accompanied by songs. Songlines are pathways in which knowledge is shared, memorised and recalled by walking and singing, with stops for rituals and rock paintings, thereby embedding knowledge in landscape. Knowledge is filed in country, between earth and sky.

Helping our students learn and connect online

In the physical classroom, we might use drama activities such as frozen pictures, soundscapes, or games based on sports; the more active the better. Australian Memory Champion, Anastasia Woolmer, shows how she uses her dance training to scaffold her memory.

The goddess of memory, Mnemosyne, was mother of the muses. Creativity supports memory.

In our teaching, we may have assessment tasks that are multimodal and weight-bearing. However, we can also provide opportunities for students by setting up creative plenaries, either at the end of a lecture or tutorial or as weekly, non-compulsory, contributions to a discussion board.

Examples might include:

- Express a concept visually – post an image connecting it to your learning and use the image as an analogy.

- Create and post a video about something you have learned in the unit so far.

- Make a meme to express something you have learned in the unit so far.

- Share a mnemonic – a device, such as a formula or rhyme, used as an aid in remembering.

- Draw in stories from current affairs – relate something about this unit to real-world current events.

- Image analogy – teacher uploads images of random objects and students explain how the objects relate to their learning.

- Share your learning as a graphic organiser

- Share a mnemonic based on an object – see Unjaded Jade who used this ancient technique without knowing how old it is.

- Choose an object on campus – it may be a gargoyle, a garden, a cafe or a classroom, to encode with learning from this unit – share with your classmates.

- Abecedarian revision – Starting with A, write a statement about content from the unit. The next post starts with B, and so on.

- How are you organising your notes for revision? See Unjaded Jade’s flashcards that combine images (pictographs) with text.

- Present a reflection on your learning in a nominated form

- Create games like bingo cards or Top Trumps about the unit content.

- What if? What if you did not know this information? Present this as a particular form.

Students using a discussion board in weekly non-compulsory activities learn together and form a sense of belonging to a cohort of learners. They get to know each other as they synthesise their new learning into their own interests. They can collect notes to revise before exams. These are neither weighted activities nor tutorials.

This also ties to principles from Universal Design for Learning (UDL) – providing i) multiple means of engagement, ii) multiple means of representation, and iii) multiple means of action and expression to maximise your students’ ability to learn and express their learning. It maps to the higher-order outcomes in Bloom’s revised taxonomy. For more ideas see Phil Beadle’s books Dancing About Architecture and The Ultimate Plenary Book.

In using creative plenaries, ancient memory devices, we can also tie these types of activities to our Indigenous Strategy.

As we understand more about how ancient peoples thought and learnt and remembered, and how they encoded memory devices in place, we can begin to understand how destroying or dividing sacred sites is like destroying the encyclopedias, libraries and universities of ancient peoples. Ancient knowledge may be partially spiritual but is also situated in concrete reality. This is true for Australia’s Indigenous peoples and provides a way to value their knowledge which is filed in Country and recognise this intelligence.

Students of the University of Sydney report they lack a sense of belonging at the University. In student surveys, the lowest-scoring category is Learner Engagement. The average positive rating for Learner Engagement in 2020 in the Higher Education Student Experience Survey was 44%.

By asking students to encode their learning into objects on campus, we can engineer a sense of belonging and even help our students file their knowledge on campus.