Toward the end of last year, a colleague and I published an article about our experiments with using ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for postgraduate course development. Following another year of experience with ChatGPT and similar generative AI tools in an educational setting, I thought it worth reflecting on our outcomes.

Our research used a self-study methodology, contextualising ChatGPT as a ‘virtual colleague’ to see how helpful it would be in the creation of masters level design course development materials. Examples of the tasks that we asked of ChatGPT included generating appropriate teaching materials, such as design briefs, student assignments, tutorial activities, and course outlines.

Thinking critically

While our findings and concluding discussions were mixed, it is important to stress the pedagogically design-focused aspect of our study. Design, particularly in its academic format as established by theorists such as Nigel Cross and Bryan Lawson, has long situated itself as a distinct discipline, with unique ways of thinking and practicing. This is something that academics have pointed out has been extended into industry, through practices such as Design Thinking. This design-focused aspect means that our conclusions may be less critical in other disciplines.

Overall, some of our findings identified weaknesses in ChatGPT when dealing with core design principles, such as critical thinking, reflection, and creativity. By contrast, the content generated by ChatGPT was structured, ordered, and generally highly knowledgeable in a broad sense. After all, one of its strengths lies in aggregating existing information – and there’s plenty of that around.

Some of the good stuff

We identified the following strengths of ChatGPT as a virtual colleague for helping to create design coursework materials:

- Acknowledging its knowledge synthesis aspects, it showed great potential as a brainstorming tool – valuable for idea generation. Such abilities have the potential to save time and also identify topics that might potentially be overlooked.

- It has the potential to rapidly create structured unit outlines and content, in response to human prompting. This largely manifests as broad-based templates that educators can then customise as required.

Overall, we found ChatGPT to be impressive for its designed purpose, as a language model for brainstorming, structuring and editing, as well as providing on-topic template-style output in response to careful human prompting. We also tentatively agreed with other researchers, that it had the potential to “[…] help both teachers and students to improve teaching and learning experiences”, as well as possibly aiding efficiency and reducing teaching workload.

Some of the ‘less good’ stuff

However, last year we also identified challenges and flaws:

- ChatGPT requires strong human oversight and does not replace the role of an education designer. Instead, our experience aligned with research indicating that its potential is limited to a supporting role.

- ChatGPT’s adeptness at producing coherent-appearing content, often resulted in generic and non-specific content, manifesting as boilerplate templates. As some researchers have suggested, this is indicative of ChatGPT’s current lack of higher-order thinking.

- We found that using ChatGPT to produce satisfactory learning materials for design students required considerable, and often very assertive, targeted human prompting. Even then, ChatGPT’s generic output led us to reflect whether ChatGPT offered much specific value to design pedagogy.

- ChatGPT appeared infuriatingly inept at identifying (and differentiating between) design disciplines, or engaging with specific aspects of design – such as notions around creativity, disciplinary processes, and professional practices.

Overall, despite creating content that is broadly well-structured, ChatGPT appeared to lack the nuance, context, creative input, and critical reflection that are the essence of design practice and the learning experience. Indeed, perhaps the most pressing consideration in relation to ChatGPT’s current flaws, is the degree to which an over-reliance on AI-generated content risks homogenising design education to such a degree, that it may stymie the learning of critical and creative insights, in favour of formulaic, regimented, or even rote learning.

Don’t smash it up, but remain vigilant

A year on, my mind remains open, but perhaps more critical, to AI as a virtual colleague. In coming to some of these conclusions, I am mindful of not opening myself up to accusations of Luddism. However, the Luddites, in contrast to some popular portrayals, were not against technology. Aside from social and economic aspects, the Luddites were actually opposed to the ways in which technology was being used to deskill their practices. Similarly, I feel that academics and teachers ought to remain open, yet vigilant, about generative AI technologies for course development.

So what now?

As educators, questions remain as to whether artificially generated, and often homogeneous, educational outcomes are beneficial educationally for a syllabus aimed at designers – or indeed other disciplines. We may not be able to control (let alone identify) when our students are using such technologies. However, as educators creating learning materials, it is worth being mindful about negatively impacting the creative, critical, and analytical scope of future industry professionals, regardless of the discipline.

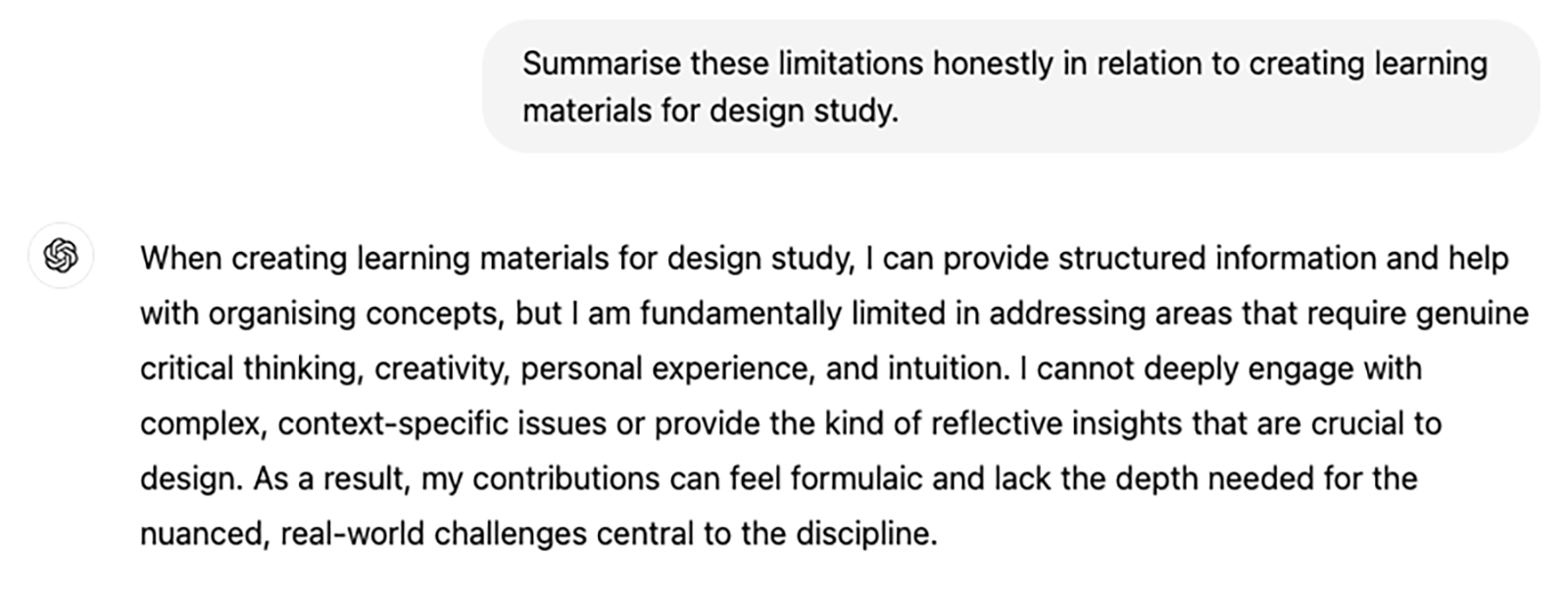

Perhaps, with a little careful prodding – sorry, prompting – the final word can be left to ChatGPT itself: