Inclusive teaching describes a range of teaching approaches that consider the many different needs, backgrounds, and ways of learning of all students. Knowing how to build inclusive teaching practices into your classroom can be tricky, particularly in the new context of remote learning.

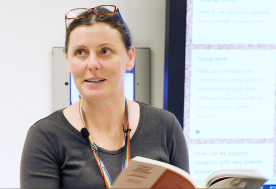

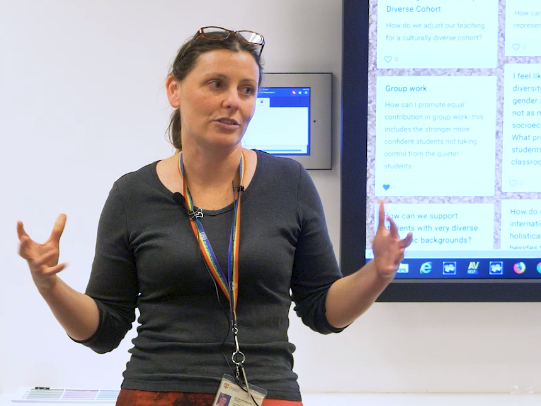

To help navigate this challenge in your classes, either online or face-to-face, Educational Innovation recently sat down with Dr Samantha McMahon from the School of Education and Social Work, to discuss the ways in which teachers can build inclusive and engaging learning environments.

Educational Innovation (EI): Can you introduce yourself to our readers? What is your field of focus?

Samantha McMahon (SM): Hi everyone, I am an educational sociologist in the Sydney School of Education and Social Work, teaching our students who are qualifying to teach in early childhood, primary and secondary school settings. I also run some professional learning courses for teachers who are already working in schools.

Educational sociologists are obsessed with educational equity. We are always trying to seek answers to why teaching opportunities don’t produce equal outcomes for all social groups. My passion is moving beyond describing these problems to inspire teachers to level the playing field. My research really focuses on how different ways of knowing students can impact how inclusively you might teach them. You can read a sample of my research via Pedagogy, Culture, and Society.

EI: Starting off, I’d like to ask how you approach the challenges of online teaching. What advice do you have for teachers working in this space and making the pivot from face-to-face to remote online teaching?

SM: It goes without saying that there has been an enormous amount of work done by teaching staff to adapt their lessons to suit online learning. With that said, there is a danger in seeing online learning as another ‘thing to blame’ for inequity in teaching. I’m thinking here, for example, of Chris Sarra’s work at the Stronger Smarter Institute and his focus on asking educators to take responsibility rather than blame things external to themselves for what can and can’t be achieved in classrooms.

There is a danger in seeing online learning as another ‘thing’ to blame for inequity in teaching.

Last semester, it was reasonably common for myself and colleagues to say things like “we just can’t do that online”. I’m totally honest about the fact that ‘online teaching’ isn’t my speciality – there’s plenty of wonderful literature out there already on this. I kind of got better at teaching online when I stopped saying ‘can’t’ and started asking better questions: “what pedagogic principles drive what I normally do?” and “what online platforms and technology can help me appropriate these into an online learning space?”. When you come back to basic pedagogic principles, I find teaching discussions turn from ‘tips and tricks’ to creative problem-solving. Some of the core principles I try and keep in mind are engagement, trust, participation and assessment.

I kind of got better at teaching online when I stopped saying ‘can’t’ and started asking better questions

EI: Picking up on engagement for a moment, do students engage with a lesson in more than one way? And, the million-dollar question, how can we tell if students are engaged?

SM: Great questions. There’s a bit of a disconnect between the technical definition of educational engagement and how university educators use it colloquially. A useful starting point is Jennifer Frederick’s and colleagues’ theorisation of engagement as having three dimensions: behavioural, emotional, and cognitive. If we think about these multiple dimensions of engagement, we can think about multiple ways of recognising and responding to student engagement more broadly.

We often associate engagement to visible student behaviours and emotions such as boredom or disaffection. The online equivalent could be, for example, the Zoom ‘black box’. Notwithstanding reasons of internet bandwidth and privacy, why do students not appear to engage in their own learning? In their research, Parker Palmer and Nell Noddings show that classrooms can be fearful places. To them, students often associate participating in discussion with risk-taking. For this reason, I re-conceptualise student behavioural engagement (or participation) as an act of trust, and in some sense, bravery.

I re-conceptualise student behavioural engagement (or participation) as an act of trust, and in some sense, bravery.

There are numerous strategies you as a teacher can use to build trust and lower the risk level of participation for students:

- Foster trust by trusting students with your own stories. Tell a story from your own life to introduce or convey a key concept. One example of this is the way AIME mentors engage their participants via storytelling.

- Don’t actively monitor student discussion. Allow your students to engage in well-supported group work in their Zoom breakout rooms. You have the option of keeping participants accountable in group work tasks by asking groups to generate artefacts/products or preparing a contribution to a whole class learning experience (e.g., question generation trees, discussions or debates). Well-supported group work may include activity prompts provided in advance via Canvas and the selection of social, procedural, and epistemic scripts to help groups work together (for more details on these scripts, see Kaendler et al, 2015). For example, you might provide procedural prompts or assign roles to group members (such as timer, scribe, reporter etc.), or you might also look at structured and predictable thinking routines like those found at Harvard University’s Project Zero.

- Be the expert AFTER you’ve been the facilitator. Tip the balance of power in the classroom. Collect everyone’s questions (including yours) into a massive question list, theme them, get students to help each other out with the answers they immediately know/can share, then divvy up the remaining questions to small groups and share back. Then, at the end of all that, I explicitly correct misconceptions or ‘value add’ to student derived understandings.

- Position student peers as experts in given weeks by rostering different students each week to facilitate breakout rooms and peer-review tasks.

- Thank students for their questions and acknowledge the intellectual quality of the questions asked.

Be the expert AFTER you’ve been the facilitator [and] tip the balance of power in the classroom.

EI: From a behavioural engagement standpoint, how can teachers create learning environments that are inclusive and open?

SM: If the problem seems to be that students aren’t ‘doing’ what you’d like them to, such as not participating in an activity or answering a question, then we can reframe that question by remembering that learning involves risk-taking. Students respond better to participatory prompts if the level of risk is reduced. Here are some strategies that may be valuable here:

- Don’t ask for volunteers! Ditch the ‘hands up’ rule! This link takes you to a two-part documentary based on Dylan Wiliams’ work in UK secondary classrooms and the damage of the ‘hands up rule’ features strongly in this documentary. Ask students questions directly but temper this with lots of warning/preparation time. If you do this, keep a class roll near your computer and tick off who you’ve asked a direct question or for a comment it’s an absolute challenge to get to everyone but it’s worth it.

- In Zoom, encourage people to leave ‘mics on’ so it is literally one physical step easier to ‘speak up’ when you feel moved to do so. If more than one person speaks at a time, trust that they’re adults and can resolve this easily.

- Allow your students to know what’s coming. Give students your learning materials (tutorial slides/questions) in advance and avoid using ‘surprise’ texts as a stimulus in-class activities. Similarly, use familiar question prompts or thinking routines each week to allow students to anticipate how you will engage a topic. Give students time to prepare and time to discuss before calling on them. To this end, never use Zoom Breakout Rooms for less than 7 minutes at a time. During whole-class discussions, give students some warning: “James, in a few minutes I’m going to ask you what your group thought about XYZ – so have a think on that for a bit and I’ll get back to you”.

- Do before you discuss. Discussion should always come last! Design a learning activity that precedes the discussion. This way, your students will have shared experience and ideas to draw on during the discussion.

- Ask good questions – in each tutorial or lab, ask at least a few questions that don’t have right or wrong answers. For some examples, turn to a Socratic question guide.

Do before you discuss. Discussion should always come last!

EI: What do you mean by emotional engagement? How can we assess or support this level of engagement in our classrooms?

SM: This is a complex question and something I’m continuing to grapple with. We know that students remember things they learn that are attached to emotion. You might remember something because it made you laugh. I remember a lot of my high school history because it made me cry. Another way to think this through is to provide the means for emotional connections for and with our students so that we build learning communities.

Here are a few suggestions that you may find useful:

- Get to know your students! You can do this as you allocate groups, group roles, and design group tasks. You can ‘rig’ the break out rooms for all sorts of reasons. This does take time, so if you’re going to manually assign students to Zoom breakout rooms, have your lists ready and set an individual task like watching a 5-minute video or writing an individual reflection immediately before the breakout room discussion so that you have time to do this.

- Provide space and be available to help during class and in structured ways outside of class time.

- Be responsive to collectivist cultures. For many First Nations and Asian cultures, especially, there is a focus on collective responsibility to the group rather than a focus on individual advancement. In classrooms, rather than individual spotlighting (asking individuals to present an answer), perhaps ask students for answers on behalf of their small group discussion. This might also help negate the effects of ‘tall poppy’ syndrome in Australian classrooms.

- Challenge knowledge claims that might cause students discomfort – for example, if someone says something racist or sexist. This lets students trust that you have their emotional safety prioritised. Ensure that class discussion is linked to evidence or course readings and don’t let things sit at the level of opinion (especially things said that can be harmful or discriminatory). Check out Di Angelo and Sensoy (2014) for more insights on this, especially if teaching sensitive topics.

- Reflect on how emotions shape your own teaching approach. This will help you create a safe, student-centred learning environment.

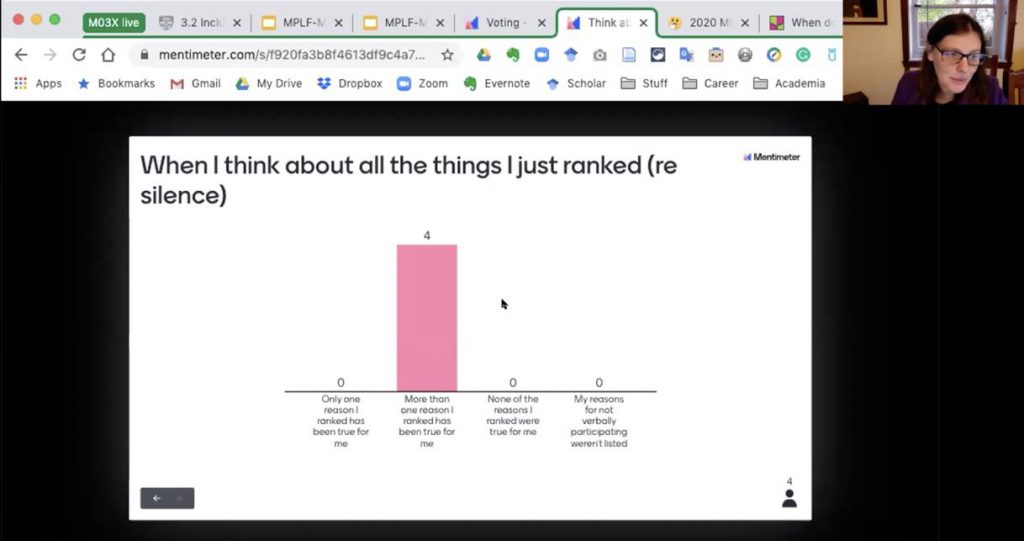

- Trust is built on feedback loops and follow-through. At a series of points in the semester, use anonymous exit slips with question prompts designed to let you know students’ emotional and intellectual connections to the course. Afterwards, use these resources as the basis for your delivery of content the following week – show students you read the exit slips and you’re doing something about it.

- Provide timely, kind, specific and actionable feedback that prompts thinking for the student. If you can, you should try to provide feedback that goes beyond providing a comment/compliment/complaint. Instead, ask a question, share a resource, or provide a specific instruction on how to improve. In the inclusive teaching professional learning modules I’ve helped with here at Sydney, when asked to talk about a time they’ve felt included, many academics recall receiving valuable and highly usable feedback.

Trust is built on feedback loops and follow-through.

EI: How can we recognise when our ‘disengaged students’, or perhaps it is better to say ‘those who appear behaviourally disengaged’, are actually cognitively engaged?

SM: This question seems to be increasingly popular at the moment, with so many of us attempting to decipher a response from the Zoom “black box”. Are people with their screens off not doing anything? To me, this is a part of a bigger question. Why do we have to eyeball people, whether face-to-face or face-to-laptop, to ascertain whether students are intellectually engaging with the content? While we are uncomfortable with not being able to see student’s facial reactions, we are often guilty (ourselves) of multitasking on Zoom to stay afloat during a difficult semester. If we give our students the trust we give ourselves and provide them with opportunities to demonstrate their intellectual engagement, we can correct this assumption.

There are a number of strategies that can help to illuminate cognitive engagement, such as:

- Re-focusing assessment around intellectual and cognitive engagement rather than behavioural participation.

- Designing ongoing, or rolling or formative assessments on a week-to-week basis before seminars. For example, weekly quizzes, debates, reflection journals, lab reports, discussion board posts, pre-class submissions etc to monitor student understanding in ways that are separate to class “participation”. See the work by Black and Williams (1998) for more on this.

- Providing multiple and varied ways for students to communicate their learning. I recommend taking a moment to review the Universal Design for Learning (UDL) principles for task design to help with this.

- Connecting classwork to assessable activities to ensure greater student “buy-in.”

Why do we have to eyeball people, whether face-to-face or face-to-laptop, to ascertain whether students are intellectually engaging with the content?

EI: For students with additional languages, university teaching and learning can be challenging. How can we as teachers support them in their study?

SM: We need to upend deficit conceptions of students with additional languages. Remember, these are intelligent humans who are proficient in more than one language. More than that, they’re using their additional language to seek out a tertiary qualification. Recognising their outstanding capacity for learning might help positively shift our expectations of these students.

Some ways we as teachers can help include:

- Using Know Your Students to understand what language skills are in your class.

- Learning names (correctly pronounced) and have a go at learning words like “hello”, “please”, “good”, “thank you”, and “goodbye” in the language of your students. If students see the effort you are putting in, they could feel an increased level of belonging.

- Allow mother tongue groups when starting out, and then jigsaw with other groups and extend with English speaking groups later in the learning arc.

- Revisiting key concepts, tutorial materials, assignment sheets, and rubrics for clear and consistent language and formatting (see Graham et al., 2018).

- Ask yourself, can all of your students see themselves in your curriculum? If not, reconfigure the readings and learning materials so as to ensure they see their voices heard in your unit of study.

- Quarantine assessment marks for written and verbal expression and maximise marks for evidence of conceptual understandings.

EI: Thank you Sam! This has been an enriching and incredibly useful chat. On behalf of Educational Innovation and our Teaching@Sydney readers, thank you for your valuable insights and practical approaches into inclusive and supportive teaching!

SM: You’re very welcome. This is just my curation of a few ideas that are very old in the discipline of education. I didn’t make them up, I’m just not that clever! A teaching qualification is a wonderful thing to pursue for deeper insights.

Want to know more?

For more information on inclusive teaching and engaging your students, we recommend:

- Checking out the Teaching Resources Hub module on Inclusive Teaching, which includes some great insights from students from underrepresented cohorts at Sydney as they talk about their experiences around coming to university.

- Coming along to one of the Modular Professional Learning Framework (MPLF) sessions (available to all University of Sydney staff):

- Visiting the COVID Canvas site, for an overview of resources to support teaching off-campus.

- Engaging with the recordings and resources compiled from the Teaching Well and Supporting Students During COVID-19 symposium

Further reading

If you are interested in taking a deeper dive into some of the topics raised above, Sam recommends checking out some of the following literature:

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Inside the Black Box: Raising Standards through Classroom Assessment. The Phi Delta Kappan, 80(2), 139-148. Retrieved February 15, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20439383/

- Di Angelo, R. (2014). Leaning In: A Student’s Guide to Engaging Constructively with Social Justice Content. Radical Pedagogy, 11(1), 25–53.

- Fredericks, et al. (2004). School engagement: potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74, 59-109.

- Graham, et al. (2018). Designing out barriers to student access and participation in secondary school assessment. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45, 103–124.

- Kaendler, Celia et al. (2015). Teacher Competencies for the Implementation of Collaborative Learning in the Classroom: a Framework and Research Review. Educational Psychology Review 27 (3), 505–536.

- McMahon, S., et al. (2017). Lessons from the AIME approach to the teaching relationship: valuing biepistemic practice. Pedagogy Culture and Society, 25 (1), 43-58.

- Noddings, N. (1995). Teaching Themes of Care. The Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 675–679.

- Palmer, P. J. (2007). The courage to teach: exploring the inner landscape of a teacher’s life. San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass, John Wiley & Sons.

1 Comment