Having survived semester 1’s rapid shift to online teaching, members of the University of Sydney community gathered together to celebrate and learn from some of the university’s ‘ordinary people teaching well during extraordinary times’ at our fully online ‘Teaching Well and Supporting Students During COVID-19’ symposium. Seeing 485 attendees from 26 institutions and #SydTeach2020 trending on Twitter at number 1 in Sydney and number 4 in Australia, engagement reflected the importance of teaching and learning in a sector and world undergoing irrevocable and unprecedented change.

In a landscape marked by uncertainty, the role of educators has never been more important. The morning of the symposium featured sessions with academics teaching radically different cohorts and contexts. This T@S article aims to draw together and share those stories of front-line teaching during the pandemic. Amongst the plethora of technologies and creative approaches, what was most notable was our shared humanity. It seems that the pressure cooker of the pandemic had distilled what was essential.

As we look towards semester 2 and beyond, we report back from this event to share how teachers at Sydney used innovative and often simple teaching approaches to effectively move to remote teaching, assessment, and student support in ways that have helped students to feel connected, engaged, secure, and that they belong.

This article was contributed by Jessica Frawley, Samantha Clarke, and Adam Bridgeman.

What do our seven key pandemic pedagogy principles look like in practice?

1. Build teacher-student relationships

Use the ‘right’ technology for the job

Jane Garvan, Visual Art academic, and many other speakers used multiple technologies and mediums of communication to build teacher-student relationships, depending on the purpose, such as posting regular video messages to Canvas to communicate changes as they happened or using discussion boards to answer ongoing class questions. Victoria Rawlings and Remy Low from Education even used the social media platform WeChat to support informal, ongoing communications and to build community with students stuck in remote locations. Across all sessions was a diversity of tools and technologies from Padlet, Mentimeter, Zoom chat, Piazza and (of course) Canvas.

Give the gift of attention – notice your students

Though specific technologies can be tools in this, very often it was the human act of noticing, paying attention and making your attention clear and visible to students. Helena Nguyen, Anya Johnson, Maria Ishkova and Mesepa Paul from the Business School found that it was the “little points” where you could give individual feedback, acknowledging that they’ve done the work and that you’ve seen it or if you notice that something has happened or if someone has been a bit down or flat that you take notice of that and let them know and have that interaction. When doing this at scale, the Student Relationship Engagement System (SRES) was useful for providing individual feedback.

Simple can be effective

As Veterinary Science academic Peter White acknowledged, even simple approaches like responding promptly to student email make a difference and let students know that they are valued and important. Likewise, Sydney Nursing School academic Jacqueline Bloomfield and others demonstrated the efficacy of hosting Zoom drop-in sessions as informal places for staff and students to connect. Drop-in sessions gave students an opportunity to clarify assignments and content while 1:1 online meetings could provide confidential support to students who are struggling.

It’s the little things that count

It’s the little things such as responding promptly to emails and discussion board posts, or simply having a photo of the teaching team on Canvas that helped foster relationships. Many speakers posted short videos to keep students up to date with changes. Notably, Sociology and Social Policy academic Estrella Pearce created a short video for her students showing them how to navigate the unit of study Canvas site so that they would know where things were. Likewise, Health Sciences academic Jennifer Smith-Merry found that short 1:1 check-ins with students were a useful way to offer out of lecture support. With just 10 minutes per student these helped to connect the teacher to their students in a way that was not possible during lectures. Alternatively, the Faculty of Engineering’s Young No found that opening the lecture 15 minutes early was another small way to allow for informal chats.

2. Foster sense of belonging and community

Listen to student preferences and give them agency

To find out what was working for their students, Media and Communications academic Margaret Van Heekeren and Health Sciences academic Jennifer Smith-Merry both used custom surveys to learn what was working for their students. This was important, says Margaret, for giving students agency when so much was out of control.

Create a shared and continuous motif or point of reference

Featuring digital Caramello Koalas in her online course, Margaret Van Heekeren reflects that “It wasn’t the chocolate per se but what is represented – community and continuity”. This strategy focused on using symbols to build a community of practice around humanity, empathy and humour and bringing some of the face-to-face features online.

Bring others into your community through team teaching and guest speakers

Variety in online conversation and discussion can be important – Psychology academics Caleb Owens and Shaun Boustani found that having two presenters and inviting guest speakers assisted in the success of their interactive Zoom webinars in their first-year psychology subject.

3. Have clear communications and expectations

Keep your resources and Canvas site clear and consistent

Several of the speakers spoke of the power of having a well-maintained Canvas site. Simple things such as how you label and store resources: “The thing I found most important was that lecture recordings were very clearly labelled and very easy to find” (Peter White). Canvas ‘modules‘ were also a powerful way of keeping things consistent, students knew where to find things and in what order to attend to these.

Use chunking and branching to manage content and different learner needs

Education academic Alyson Simpson discussed how she used chunking and branching in teaching pre-service teachers how to teach literature. Alyson found Zoom breakout rooms easily replicated small table discussion groups noting that teaching staff had to “keep walking through walls to get into the rooms“. Chunking content into meaningful activities provided structure and limited cognitive load while branching allowed students to choose alternative activities. In her example, Alyson noted that following one chunk of content, students in a tutorial would have a choice activity 1 (branch 1) or activity 2 (branch 2). While both branches relied on the same prior learning, one branch required students to apply this learning in a more challenging way, supporting student choice and agency, while catering for diversity within the cohort.

Communication is important for the teaching team as well as the students

Victoria Rawlings and Remy Low also supported their tutoring team by providing weekly updates as a means of regular and supportive communications while not ‘over messaging’, supplied session templates and resources to help tutors structure and deliver their online teaching effectively.

4. Measure and support engagement

Recognise what you can and cannot measure in online participation

Whether assessed or not, Business school academics Helena, Anya, Maria and Mesepa realised that measuring online participation is difficult. Students may be engaged but for technical reasons need to turn off their camera. Instead, the team developed a rubric to clarify what it meant to engage in an online class. These rubrics were developed in consultation with students and were reweighted to focus on pre-work so as not to unfairly disadvantage those who cannot always visually participate.

Design for interactivity and feedback

Young No from Engineering used interactive surveys and quizzes across a series of different tools. This allowed for two way interaction between tutor and students, provided ways for students to self check in and receive feedback, and build teacher-student relationships.

Privacy or anonymity can be important

In teaching first year Psychology, Caleb Owens and Shaun Boustani said how important the ability to contribute anonymously can be to fostering discussion. Owens and Boustani used Mentimeter to allow for different kinds of interactive contributions which can provide safety and security. For others, privacy was sufficient, with Peter White finding students frequently used private messaging within Zoom chat to ask questions that might be perceived to be silly or embarrassing.

For engagement, don’t be afraid to adapt – “now more than ever one size does not fit all”

When crimonology academic Estrella Pearce started online teaching in Semester 1 many of her students were in the process of travelling, either back to their home countries or to other parts of Australia. For this and other reasons synchronous teaching did not work – at least not at that point in the semester. Instead of taking a single approach for the entire semester she adapted her teaching to suit changing conditions by beginning with pre-recorded asynchronous sessions and then, as students settled and adapted, conducting synchronous sessions later in the semester. This better engages the diversity of student needs.

5. Engaging content delivery

Zoom is not the same as face-to-face – do not transplant the traditional lecture

During the pandemic many have highlighted the inefficacy of using an hour of synchronous time to lecture students. Surely, if this is all we are going to do it could be recorded and put online. Victoria Rawlings and Remy Low reflected that “We quickly realised […] we needed to diversify our modes of delivery [when we moved online]” and took a “no transplanting” approach when designing and delivering online learning. Some surprisingly simple touches can transform online engagement. Engineering academic Young No used Google Docs to create real-time student interactivity in class and allow for communal discussion while creating a shared student-generated resource. In first year Psychology, Caleb Owens and Shaun Boustani downloaded Mentimeter questions and uploaded these as a resource to Canvas for asynchronous learning for those unable to engage synchronously.

Experiential and authentic learning is hard but possible

It is hard and probably unwise to try to replicate all experiences and learning online – some ‘hands on’ and experimental tasks require use of materials and instruments and run the risk of becoming trivialised if shifted online. However, other skills can be developed and practiced online, with the greater range of media and tools available enhancing that available in a physical setting. In shifting their allied health placement simulation online, Merrolee Penman and Jennie Brentnall from Health Sciences ensured that students followed approaches used in telehealth interventions. By deliberately scaffolding the tasks for students, cognitive overload for students was reduced and they received regular feedback on their progress. Given the complexity of the tasks, training for staff in using Zoom was key and the use of a backchannel for staff (they used WhatsApp) to keep the sessions flowing as seamlessly as possible was very effective.

Try simulations or role-play for an immersive learning experience

Eyal Mayroz from the Department of Peace and Conflict studies engaged his postgraduate students through an immersive whole-day simulation of a model UN. This simulation was run using Zoom online and also constituted the major assessment for this study.

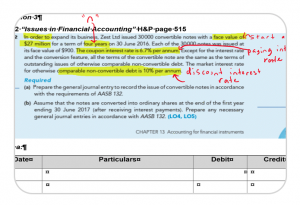

Additional content or support may be needed

“Sharing teaching thinking in a remote and online environment is challenging and if it is challenging for us, it’s challenging for the students!” said Louise Luff, a lecturer in financial accounting. As part of her unit in the Bachelor of Commerce, Louise used ‘Online Skills Workshops’ to unpack and demonstrate professional skills and “work along” questions in Excel for the challenging topics. This gave students a chance to work alongside their lecturer on challenging tasks and build skills that are relevant and connected to the real world. In addition, the provision of weekly topic recap videos answered student questions and unpacked confusing points.

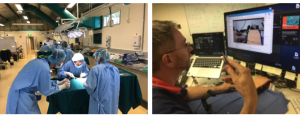

Embrace the risks and rewards of live demos

Kate Mills and Denis Verwilghen engaged their veterinary science students by doing live video demontrations suturing using a skin simulator. Students received suturing kits in the mail prior to the session, and were able to get live feedback on their practical skills through their webcam and Zoom.

6. Meaningful assessment, feedback, and academic integrity

Rubrics and exemplars clarify expectations

Online assessment is new to students as well as staff and it is important to provide clear instructions and clarify expectations. Several speakers used clear marking rubrics and exemplars from past submissions to help set clear expectations for students and reduce anxiety.

Use formative feedback and quizzes

“The students loved the revision quizzes, they loved the competition and engaging them in those like a game was fun and they learnt a lot!” said Jacqueline Bloomfield. Several speakers used online quizzes to provide regular, ongoing feedback for students and found students enjoyed these opportunities to check-in, revise and test their understanding, and compete in a low stakes way with their peers.

“To retain the assessment…we just had to be more creative!”

When a traditional practical skills demonstration assessment was made impossible, Helen Parker, a lecturer from Health Sciences, reimagined her assessment and turned the students from ‘demonstrator’ to ‘assessor’, asking them to instead take on the role of ‘examiner’ and assess a typical student’s performance of practical skills using video submissions from students in previous unit. The key learning outcomes for the students were still met, just in a more creative way!

Help students to think like the assessor

Jacqueline Bloomfield introduced a new “plan your own exam” activity where students were asked to submit an exam question (and answer) that they anticipated would be in the final exam. This encouraged students to reflect on what was taught over the semester, formed the basis of the revision sessions, and even informed some of the actual exam questions as an added incentive.

Question banks promote academic integrity

In order to “maintain academic integrity as much as possible in the online space”, Helen Parker used the simple but effective technique of question banks for her online quizzes “so no two students had the exact same exam”.

Staged feedback and feedforward

Jennifer Smith-Merry introduced a two-staged portfolio assessment to replace her unit’s mid- and end-of-semester exam to allow for feedback and feedforward opportunities. By splitting assessment into smaller parts you can scaffold learning and also reduce the stakes, since one smaller assessment can be a useful opportunity to get feedback as you prepare for a second larger one.

Multimodal and authentic

Online learning lends itself readily to the use of alternate media, In the challenging arena of musical performance, Andrew Barnes from the Conservatorium maintained the connection and motivation provided by face-to-face workshops online with the additional problem of Zoom sound and streaming quality being insufficient. He used discussion board assignments as ‘virtual concerts’ with students assigned as performers or audience members. The task of pre-recording pieces as videos ensured sound and visual quality was in the hands of students, who had to learn the additional skill of recording in their own recording studio. Similarly, when acting as audience members, students were given the responsibility of writing considered feedback rather than reflecting instantly as had happened in the live environment.

Put students in the driving seat and draw on real-world problems – including the pandemic

For Raphael Hammel’s postgraduate design students their assessment asked them to draw on their skills as designers to design and facilitate an online workshop addressing the current challenges of online teaching and learning during a pandemic. Students designed and led a participatory workshop focused on addressing this problem.

7. Be human

Technology is the tool, not the director

“When I reflected on the craziness of the preceding months it hit me that amongst all the technical bells and whistles that I had mastered […] Technology was the tool, not the director.“(Margaret Van Heekeren). Across all the talks what academics kept on returning to was the human quality: “Teaching is really a human endeavour” (Young No).

Consider the tone you use to talk to students – informal, conversational, caring

In the words of Education academics Victoria Rawlings and Remy Low: “A lot of the time it is just about talking to people in ways that just made them feel cared for”, to show “care through communication”. This theme resounded across several talks (too many to individually list or identify) that our language needed to be personal, informal and conversational as opposed to formal and distanced.

Aspects from your personal life (pets were popular) humanise you and connect you with your students

Peter White from Veterinary Science noted that after his chihuahua Pablo made several cameo appearances that he received a notable mention in the unit of study survey. Whether you have pets or not, aspects from our home life provide an opportunity to show students who we are.

Tell me more!

- You can find all the symposium related Teaching@Sydney posts online and accessible to all.

- University staff can also access all the symposium recordings and resources on the ‘Supporting Off-Campus Learning’ site.

- As we move into semester 2, Educational Innovation has developed a one-stop resource for teaching during COVID-19, based on experiences and research from semester 1: Quick-win guides for teaching in semester 2

- Get support and advice with teaching – book a 30-minute consultation with an educational designer: https://bit.ly/ei-consults

- If you need technical support with an educational technology like Echo360, SEAMS, Akari, Zoom, PebblePad, etc, skip the queue by completing our online form

3 Comments