Microbiology of infectious diseases is widely known as one of the most challenging areas for first-year medical students due to the large volume of information they need to comprehend and memorise in a short period.

Dr. Sarah Scealy, a lecturer in pre-clinical sciences at the University of Sydney’s School of Rural Health in Dubbo, has been exploring innovative ways to support and challenge her Year 1 medical students as they learn the critically important but content-heavy subject material. To help students revise the Sydney Microbiology curriculum, Dr. Scealy has repurposed a board game called “What’s your Diagnosis?” (Axler-DiPerte, 2020). In collaboration with the Camperdown Microbiology/Infectiology discipline teaching team, she has curated a list of medically relevant and assessable pathogens to incorporate into the game, ensuring that every item of game information is linked back to specific learning outcomes.

What is “What’s your Diagnosis?”

“What’s your Diagnosis?” is a board game that uses the most relevant aspects of clinically important pathogens to provide a fun and interactive learning experience. Students challenge each other or work together in teams to identify a mystery pathogen, chosen in secret from a concealed deck of cards.

The gameplay is a bit like Cluedo, where pathogens are eliminated through a series of questions by opposing teams, with Colonel Mustard and his candlestick in the library replaced by the RNA Ebola Virus in Western & Central Africa.

The game features fifty bacteria, viruses, yeasts, fungi, mold, and parasites, with two information booklets covering 500 separate elements of information. The Microbial Guide booklets function as open-book exams, with players racing against the clock and the opposing team as they develop a thesis about their ‘diagnosis’.

How does it work?

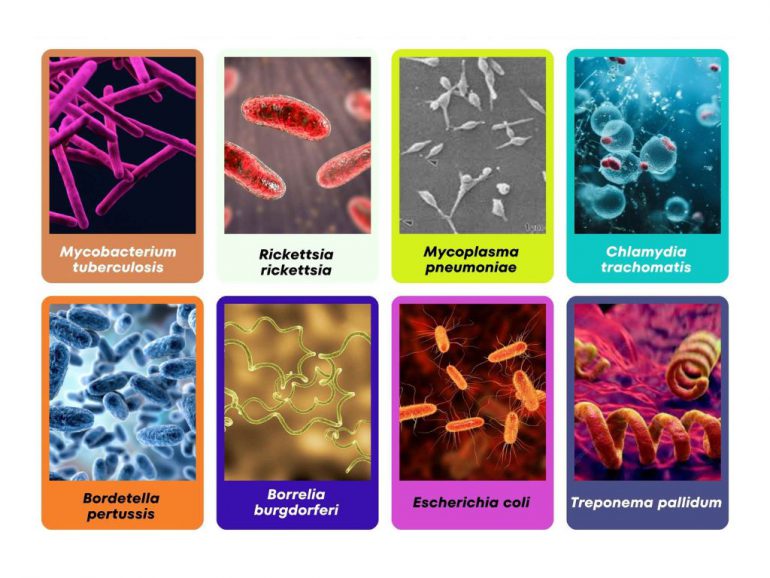

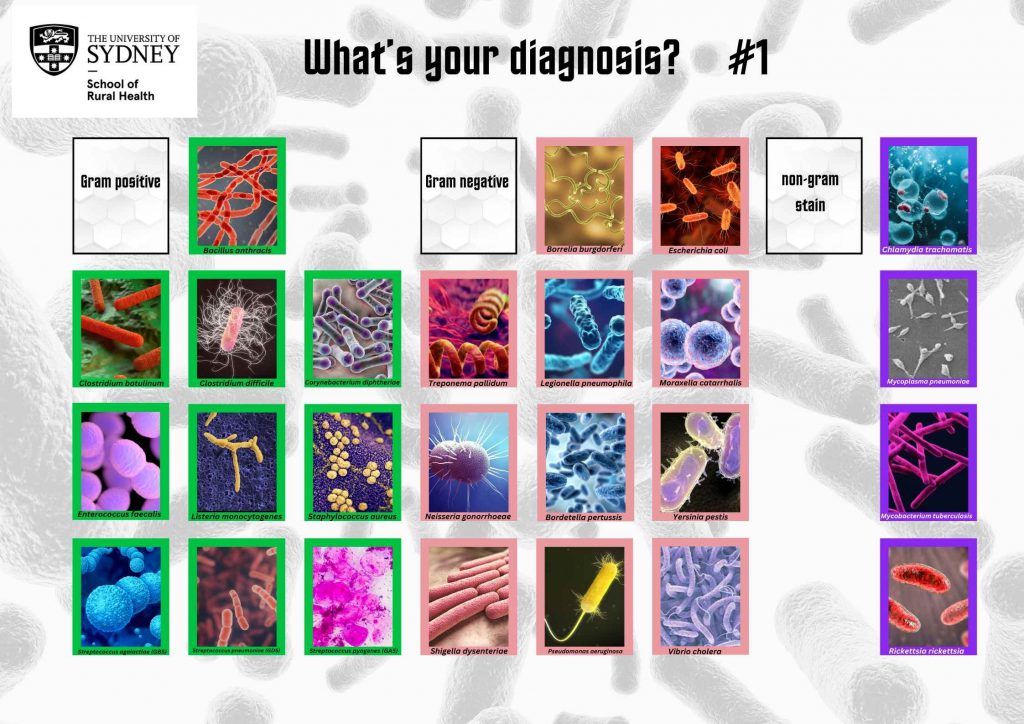

In “What’s your Diagnosis?”, each pathogen is represented by a card, and these cards are featured on the game board, classified into significant groups based on their characteristics.

The game offers flexibility in gameplay, allowing for team play among students as well as serving as an effective one-on-one or individual study tool. To begin, each side or team secretly selects a pathogen card, keeping its identity hidden from their opponents. The opposing teams then take turns asking questions about the characteristics of the infective element, using the information provided to narrow down the possibilities and ultimately identify or diagnose the mystery pathogen.

Dr Scealy worked with School of Rural Health Education Designer Lisa Hampshire to ground this version of the game in the pedagogy of game-based learning in medicine and to make the experience visually accurate and appealing. A critical aspect of maximising the effectiveness of games in teaching and learning is understanding that using games helps learners to make memories rather than assisting them in memorising content (Pitt et al., 2015).

Just because it’s challenging, it doesn’t mean it can’t be fun! By engaging students in meaningful play activities aligned with subject learning outcomes, we can move beyond rote memorisation, contextualise concepts, and create lasting memories.”

Game-based learning has the potential to yield equal or better grades and usually promotes better attitudes about learning (Pitt et al., 2015), with a positive effect on teaching and learning (Hind et al., 2015). To avoid information overload, the game has been split into two boards: one featuring twenty-five bacteria and another featuring twenty-five fungi, parasites, molds, and viruses. Each board has its own detailed Microbe Guide for players to use as they search for the correct diagnosis.

What do students think?

In the first instance, the game was played by two teams of highly competitive and motivated Year 1 Medicine students in a non-compulsory revision session, giving students time to consolidate their learning in a safe and active way. Feedback from students after the first game session led to a simplification of the microbial guide and refinement of the rules giving players more motivation to go deeper into the featured elements of each pathogen.

Students now have their own copy of the game to use for revision and the Dubbo Education team are looking forward to receiving more feedback on how it can be improved and even co-designed for future iterations.

How can I use “What’s your Diagnosis?” in my own context?

For more information about using or applying What’s your Diagnosis? in pre-clinical sciences, contact Dr Sarah Scealy at: [email protected]

Lisa Hampshire will also be presenting “What’s your Diagnosis?” at the ANZAHPE (Australia and New Zealand Association for Health Professions Educators) conference in Adelaide in July.

References

Axler-DiPerte, Grace L., and Mary T. Ortiz. “What’s Your Diagnosis? A Rapid Inquiry–Based Game To Differentiate and Review Medically Important Microbes.” Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education 21, no. 3 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v21i3.2059.

Hind Abdulmajed, Yoon Soo Park & Ara Tekian (2015) Assessment of educational games for health professions: A systematic review of trends and outcomes, Medical Teacher, 37:sup1, S27-S32, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1006609

Michael B. Pitt, Emily C. Borman-Shoap & Walter J. Eppich (2015) Twelve tips for maximizing the effectiveness of game-based learning, Medical Teacher, 37:11, 1013-1017, DOI: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1020289