The Higher Education Standards Framework legislation requires Australian universities to research and teach. Indeed, higher education is distinguished from other parts of education by the importance of both activities and by the need for the curriculum to be informed by current research in many disciplines. This “nexus” is the bi-directional relationship between the teaching and research activities so that they inform, influence and mutually support each other. Most academics and students believe that the nexus exists. Many believe it to be positive for student and research outcomes, and to be a marker of institutional quality.

As a student, my experience of the nexus was mixed. Most of my lecturers talked about current research – often their own – but the material was often too abstract or just too hard to understand as an undergraduate. It added to the complexity of the course rather than inspired my interest in it. In my final year of coursework, however, my college tutor (who I later discovered was an internationally renowned electrochemist) introduced me to the rules of magnetism in a way that energised me to read more deeply into the topic and ultimately to seek a PhD project. Goodenough’s Rules* were cutting-edge research at the time and so my reading took me beyond textbooks and to seek out conversations with people whose papers I read.

At Sydney, “research-led teaching” is considered a key dimension of education and is required for promotion applications where it is defined as “encouraging imaginative student inquiry, sharing insights from research and scholarship with students and the use of primary sources and recent discoveries as part of teaching”. Our Teaching and Learning Policy, through the principle of research-enriched engaged enquiry, also requires learning that unites “the thinking and discovery process used in research with experiential development of skills and knowledge through application”. The nexus also informs our shared teaching philosophy in which “knowledge and skills are constructed through collaborative and interactive inquiry” and where assessment is focused on “authentic problem solving and tasks” that reflect real world problems and approaches.

Empirical evidence for the teaching-research nexus

A number of meta-analyses have been published (Hattie and Marsh, 1996; Allen, 1996; Feldman, 1987) with the results generally confirmed by more recent work. The original empirical studies looked for relationships in student outcomes (mostly measured through student satisfaction surveys) and research effectiveness (such as volumes of papers and numbers of citations). The analyses point consistently to zero correlation (or sometimes weakly positive or weakly negative relationships) for individual academics and for departments. The meta-analysis by Hattie and Marsh has been particularly influential. This work has withstood rigorous scrutiny and analysis and the authors have further explained the significance of a zero relationship (Hattie and Marsh, 2002; Marsh and Hattie, 2004). Firstly, it is not a negative correlation – overall, research activity does not reduce educational outcomes for students. Secondly, zero means that there can be as many individual academics who are “as many excellent teachers and researchers as there are excellent teachers, excellent researchers, and not-so-excellent teachers or researchers” (Hattie and Marsh, 2002). It does not mean there are no academics who are excellent researchers and teachers. No differences were found between types of institutions (e.g. research intensive, technical or liberal arts), courses (e.g. undergraduate or postgraduate and liberal studies or professional) or disciplines.

They concluded that “the common belief that research and teaching are inextricably entwined is an enduring myth”.

Hattie and Marsh posited that the overall zero relationship in fact arises through a positive correlation between the ability to be a good teacher and a good research being countered by a negative correlation between time and motivation to do both. Research outputs are highly dependent on research time but more time spent on teaching does not necessarily increase its effectiveness. However, the relationship between teaching and research was found to be highest for those who spent the highest part of their time teaching, effectively zero for those with average teaching loads and negative for those spending little time teaching.

The Grattan Institute (Cherastidtham et al., 2013) has investigated the teaching-research nexus for Australian universities through a comparison of data from national student surveys (AUSSE and CEQ) and on research excellence and activity (ERA). The authors conclude that there is “little reason to believe that teaching is improved by co-producing it with research”. The level of research does not appear to “systematically affect teaching quality either way”.

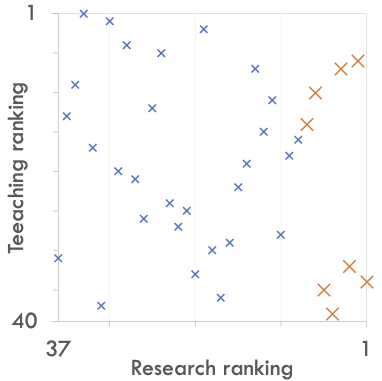

Figure 1 shows a plot of research ranking from the THE World University Rankings from 2023 against the teaching ranking from the Student Experience Survey for 2022. No relationship is apparent.

Figure 1: Plot of research ranking against teaching rankings for Australian universities in 2023. The Group of 8 universities are shown in red. Four of these rank highly in both teaching and research. The other four rank highly in research but low in teaching.

Staff views on the teaching-research nexus

Many academics believe that the relationship between teaching and research is strong, self-evident and a positive for students. The British Academy’s project on the nexus included studies of staff views before and after the pandemic. Those reporting little interaction between their teaching and research activities saw this as primarily resulting from increased teaching loads and requirements to teach outside their own areas of research.

Students’ views on the teaching-research nexus

The British Academy’s project on the nexus included a survey of undergraduate and postgraduate student attitudes and experiences of the relationship between teaching and research across a range of disciplines. Overwhelmingly, students were aware that their educators were also engaged in research activities and most did not view teaching and research as completely separate activities. Students identified publishing articles and books, developing new research ideas and keeping up to date with current research as the types of research activities undertaken by their educators.

Some students questioned whether excellent researchers were the best teachers (and vice versa). Students from across different disciplines also observed that professional or institutional pressures to research and publish might lessen willingness of academics to teach or develop their teaching practice, with teaching seen as the lower priority.

Improving learning through the effective integration of the teaching-research nexus in units and courses

Given the increasing need to develop critical thinking, research skills and an understanding of the research process in a world with easy access to information, opinion and automated content development, successful integration of research into teaching programs is perhaps even more important than ever. Practical and useful guides have been published including those by the Centre for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Melbourne (Baldwin, 2005) and by Dietis (2023). The evidence summarised above suggests that integration of research in teaching is desirable in graduates and desired by staff, institutions and most students but appears to have little effect overall.

The Principles Guiding Education at Sydney are underpinned by both the experiences of our staff and students and by empirical studies and scholarship such as that on effective teaching and the key elements that affect students’ academic achievement. Concurring with my own experience, we need to recognise that many students may not know that research is an important activity at universities and that its relevance to study may be part of the ‘hidden curriculum’ for first-in-family students. For these students in particular, passive exposure to research is unlikely to lead to engagement whilst no exposure may limit aspirations and career expectations. How can our principles and the research on which they are based inform effective integration of the teaching-research nexus for all of our students open in our courses?

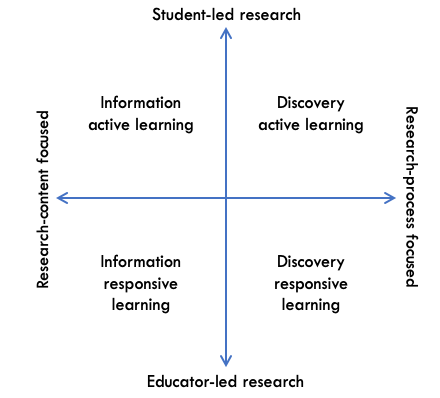

Dietis (2023) introduced the ‘frame of the teaching-research nexus’, illustrated in Figure 2. The first dimension shows the range of research-informed learning activities from “research-content focused” and “research-process focused” with the former involving searching and analysing current research and the latter focused on the creation of new ideas and knowledge. The second dimension divides these learning activities into “student-led” and “educator-led”. Student-led research involves students as active participants in the construction of knowledge through inquiry guided by the educator fully consistent with our shared teaching philosophy. In educator-led activities, students are more passive participants with learning developing through observing. Evidence from the studies on effective teaching and student achievement suggests that such activities are less likely to be effective in effective learning and hence in successfully integrating a teaching-research nexus.

Figure 2: Frame of the teaching-research nexus adapted from Dietis (2023).

The approaches described by Baldwin (2005) covering the kinds of activities that are commonly used fit well within this framework:

- Drawing on personal research in designing and teaching courses. When educators are engaged and passionate about the content, this can be infectious for students. This is primarily educator-led and context focused, fitting in the information responsive learning quadrant in the framework and is probably a very common example of research-led teaching. However, it is primarily didactic in nature and, empirical studies suggest, will not necessarily actively engage all students. As in my own experience as a student, it also has the potential to be too abstract for many students.

- Placing the latest research in the field within its historical context in classroom teaching. Ensuring students understand that disciplines are dynamic and that knowledge and ideas evolves provides context for new research. As with (1), if educator-led this again becomes information responsive learning if the students’ knowledge is too basic for them to be actively involved in the debate or the historical context is too abstract.

- Designing learning activities around contemporary research issues. Asking students to explore cutting-edge research based on the knowledge they have, from formal literature reviews to fact checking media stories, introduces research skills and exposes students to research techniques through information active learning.

- Teaching research methods, techniques and skills explicitly within units. This can be done as part of a unit of study, such as inquiry-focused laboratory work or research tasks as part of the assessment, which are student led and discovery active learning. Alternatively, distinct research method units are sequenced through a course. If taught separately to students who are not themselves completing their own research, these process-focussed and educator-led approaches (i.e. discovery responsive learning in the framework) need to be themselves full of real-world research activities and projects.

- Building small-scale research activities into undergraduate assignments. Student research projects are the ideal form of discovery active learning. They can deliver excellent student engagement and outcomes. They are often performed as group tasks, with appropriate scaffolding, which mirrors most modern research. Although such forms of active learning have been shown to be particularly important for reducing achievement gaps for non-traditional students, they have often been restricted to final year or high performing students.

- Involving students in departmental research projects. In many US institutions, it is common for undergraduates to join research teams as junior members either for credit or for payment. Although less common in Australia, summer placements and the ability for high performing students to swap units for such research experiences have been made available at Sydney. As with (5), such experiential opportunities are discovery active learning in a form that is close to that of a research student but are often reserved for undergraduates likely to pursue that pathway.

- Encouraging students to feel part of the research culture of departments. Most undergraduates will not be aware of the research interests and activity of the disciplines in which they are studying. Alongside involvement in social activities in which postgraduate and senior undergraduate students have opportunities to interact and speak informally with researchers, corridors, newsletters and displays can be alive with posters and accessible information. Although this is information responsive learning, such approaches build awareness and understanding of the volume of research that the institution is involved with.

- Infusing teaching with the values of research. If it is argued that higher education is different to ‘training’ because it is informed at all times by the way knowledge is constructed, argued over and provisional, our teaching and our assessment should always reflect this. For undergraduates, this means establishing foundational knowledge but giving experience of “confronting, messy, ambiguous and contested areas” (Baldwin, 2005) which all disciplines have. Lectures full of information, and assessments which encourage memorisation and reward students to accurately repeat it, do not model these values. Guided inquiry based (such as POGIL) and peer instruction methods, where the educator provides students with processes for building their own understanding, are examples of discovery active learning that have been shown empirically to lift engagement and outcomes in large undergraduate programs whilst also reflecting the ways in which research is undertaken.

- Conduct and draw on research into student learning to make evidence-based decisions about teaching. In most universities, obtaining a research degree is the main criteria for appointment to an academic position with little formal preparation for teaching required or exposure to research findings on students learn effectively. The empirical evidence based on ‘meta-meta-analysis’ by researchers on effective teaching and the key elements that affect students’ academic achievement reflect studies of 100s of millions of student responses and understanding.

A reciprocal relationship between teaching and research?

Most of the analyses, research and examples on the nexus focus on the impact of research on teaching. However, a nexus should be bi-directional with education informing research practice beyond students’ involvement in research projects. In the British Academy survey of students, many either disagreed that teaching influenced research or did not know. In the British Academy survey of staff, many did identify a reciprocal relationship but there appear to be limited examples in the literature.

Some of the most personally rewarding interactions with students at university are when they question ideas or seek a better explanation of a complex idea. Throughout my career, these conversations have provided me with both the need and the insight to actually understand the research – that we often do not understand concepts until we need to teach them is only a cliché because it is true. On many occasions, these interactions have turned into new research questions and publications centred around how abstract ideas and frameworks (in both my disciplinary research in quantum chemistry and in my educational scholarship) into ‘everyday’ concepts and representations.

References

Allen, M. (1996). Research productivity and positive teaching evaluations: Examining the relationship using meta-analysis. Journal of the Association for Communication Administration 2, p 77-96. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED379705

Feldman, K. A. (1987). Research productivity and scholarly accomplishment of college teachers as related to their instructional effectiveness: A review and exploration. Research in higher education, 26, 227-298. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40785234

Hattie, J., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). The Relationship Between Research and Teaching: A Meta-Analysis. Review of Educational Research, 66(4), 507–542. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543066004507

Hattie J. & Marsh H. W. (2004). One journey to unravel the relationship between research and teaching. Paper presented at Research and Teaching: Closing the Divide? An International Colloquium, Winchester, March 18-19. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/251600109_One_journey_to_unravel_the_relationship_between_research_and_teaching

Cherastidtham, I., Sonnemann, J., and Norton, A., 2013, The teaching-research nexus in higher education, Grattan Institute, Melbourne. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/191a_background_teaching-research_nexus_in_higher_education.pdf

Marsh, H. W., & Hattie, J. (2002). The relation between research productivity and teaching effectiveness: Complementary, antagonistic, or independent constructs?. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(5), 603-641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2002.11777170

McKinley, J., Harris, A., Jones, M., McIntosh, S., & Milligan, L. (2019). An Exploration of the Teaching-Research Nexus in Humanities and Social Sciences in Higher Education. London: British Academy. https://www.thebritishacademy.ac.uk/documents/4094/McKinley-et-al-An-Exploration-of-the-Teaching-Research-Nexus.pdf

* Although “blue sky” research at the time, Goodenough’s work was instrumental in the development of lithium-ion batteries and he subsequently became the oldest recipient of a Nobel Prize in 2019. John Goodenough sadly died, aged 100 years old, in June 2023.