For an incoming first-year pharmacy student, understanding how their chosen profession has evolved and developed over time will enable a better appreciation and connection with the discipline. History embodies many important lessons, from medical breakthroughs to medical disasters which fundamentally changes the way pharmacists operate. Traditionally, the history of pharmacy is taught through a series of didactic lectures providing a brief overview of the key events and people from ancient civilizations through to 19th-century pharmacy. However, incoming students enrolled in Foundations of Pharmacy (PHAR 1811) often find it difficult to grasp the broad historical concepts and see little relevance for their development as pharmacists. In a nationwide survey of pharmacy curricula delivered in the UK, online resources available through the Museum of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society of Great Britain have been utilised and found to be useful by pharmacy teaching staff. However, a visit to the pharmacy museum was reported to be the strongest preference indicated by students (Anderson and Hudson 2011). Object-based learning utilising the collection of the Chau Chak Wing Museum involved in the latter is explored in our current work. The goal was to enrich students’ understanding of the connections between the past and contemporary practice as pharmacists, linking in to the Sydney core pedagogical principle of using engaging approaches to content delivery. In particular, object-based learning takes advantage of the distinct capabilities of the Chau Chak Wing Museum to deliver valuable learning experiences in both online and face-to-face formats, and increasing authenticity by using real artefacts to increase student engagement and motivation.

Education Design: Object-Based Learning

OBL is a student-centered learning approach that facilitates deep learning through actively interacting with objects (Sharp et al. 2015). Through engaging multiple senses (sight, smell and touch) and closely interrogating objects with their peers, students are able to construct meaning and explore concepts, events and problems, resulting in a more meaningful learning experience (Hannan et al. 2013). Through engaging in an OBL activity, students refine their skills in making observations, deductive reasoning, and communication (Marie 2011) making OBL an effective pedagogy even for disciplines that do not traditionally engage with museum collections (Thogersen et al. 2018). The OBL program at the Chau Chak Wing Museum (CCWM) connects with all disciplines by embedding relevant collections in meaningful ways and focusing on key transferable skill development.

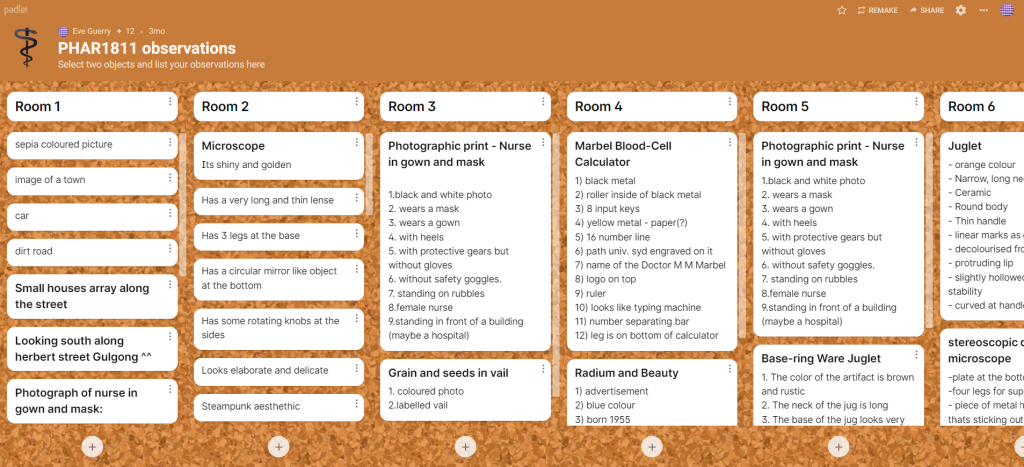

A series of three activities were designed and facilitated by the Chau Chak Wing Museum’s Academic Engagement Curators based on a curated collection of historical artefacts broadly relevant to the study of pharmacy (Figure 1). Students worked in five small teams of 5-6 people; handling select objects from this collection (Figure 2).

Figure 1. Example of objects curated for PHAR1811 available through CCWM online collections.

Figure 2. Students engaging in Object Based Learning

Activity 1

Students began the two-hour session with an interactive team-building hunt through targeted exhibits in the galleries. They were challenged to locate and respond to relevant artefacts and exhibitions with a mixture of written, photographic, and video responses.

Activity 2

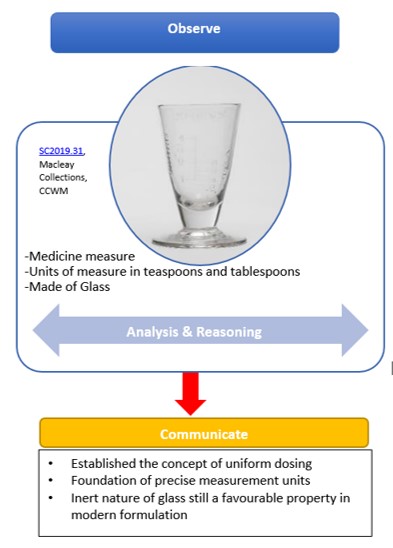

Each group was given an artefact to work with and were tasked with observing its physical attributes (e.g., colour and shape) and making inferences about its potential function. From these observations, each team then made a case for why they believed their object was the most significant for the history of pharmacy, drawing parallels between the object and contemporary pharmacy practice. Each team presented their case as part of a class discussion (Figure 3). For students joining online, digital catalogue entries were provided to groups formed in breakout rooms.

Figure 3. Schematic of learning process and making connections between the past and present.

Activity 3

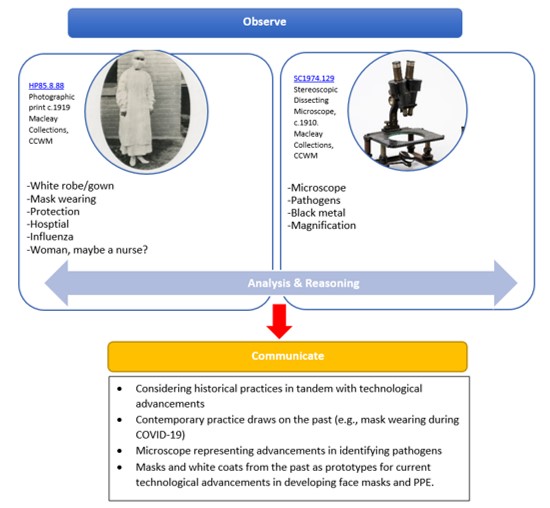

In the final activity, each team worked with a new set of two objects from the CCWM collections.

Students started with ‘deep looking’ and then moved into group discussion before forming a narrative that connected the two objects under a common theme. This theme formed the basis for a hypothetical exhibition that addressed why understanding the history of pharmacy is valuable for pharmacists. Students were able to select their target audience ranging from the general public, high school students, through to pharmacy practitioners or academics and had to consider how the identified audience influenced the way in which they communicated their message (Figure 4). Figure 5 outlines the observations made by students participating in the remote session via Zoom.

Figure 4. Connecting the artefacts to modern contemporary practice

Figure 5. Observations compiled by online cohort of students

What did students think?

This teaching approach was introduced in semester 1 of 2022 as a way to improve student engagement and interest in studying the history of pharmacy. These workshops were also used to form groups for an upcoming group assignment, offering a friendly and motivating space for students to get to know each other. Post-workshop, student feedback was overwhelmingly positive. The unique learning experience of being able to directly work with historical artefacts not only facilitated stronger student engagement but allowed students to immerse themselves into the subject and develop a deeper understanding of the connection between the past and contemporary pharmacy practice.

The museum was extremely fun, entertaining, and interesting. All activities were great fun!

(student feedback)

I absolutely loved it!!! definitely a workshop activity to implement in future years 🙂 thank you for this opportunity!

(student feedback)

Want to Know More?

For anyone interested in the possibilities of object-based learning for enhancing learning, authenticity, and the student experience in your unit, we say go for it! Have a wander through the Chau Chak Wing Museum for inspiration and get in touch with the Academic Engagement Curators at [email protected].

References

Anderson, S. and B. Hudson (2011). “Perceptions of teaching the history of pharmacy in the United Kingdom.” Pharm Hist 53(1): 22-28; discussion 28.

Hannan, L., R. Duhs and H. Chatterjee (2013). Object based learning: a powerful pedagogy for higher education. Museums and higher education working together: challenges and opportunities. A. Boddington, Routledge: 159-168.

Marie, J. (2011). The role of object-based learning in transferable skills development. Proceedings of the 9th Conference of the International Committee of ICOM for University Museums and Collections (UMAC).http://dx.doi.org/10.18452/8699

Sharp, A., L. Thomson, H. J. Chatterjee and L. Hannan (2015). The value of object-based learning within and between higher education disciplines. Engaging the senses: Object-based learning in higher education. H. J. Chatterjee and L. Hannan, Routledge: 111-130.

Thogersen, J., A. Simpson, G. Hammond, L. Janiszewski and E. Guerry (2018). “Creating curriculum connections: A university museum object-based learning project Education for Information.” Education for Information 34: 113-120.