Many PhD candidates will agree that the question “How is your PhD going” might send shivers down their spine – depending on how productive the day was. Many will advise to never EVER ask a candidate this question.

Perhaps more important, but rarely asked, is the question “Where is your PhD going?” in relation to the candidate’s future aspirations, and personal and professional ambitions. This is important because most PhD candidates aspire to academic careers but more than half of the graduates will not score a long-term academic appointment, and sadly, many will withdraw for various reasons. This raises the question about alignment:

Should doctoral education adjust its structures and methods to meet changing post-PhD career outcomes?

While previous research shows transferable skills are requested for post-PhD careers (academic and non-academic jobs), we wanted to know: what are the skills PhD candidates start off with. We looked at the selection criteria of thousands of PhD programs to find out.

See a visual research summary below and read the full paper (open access) for details on methodology and the findings:

A practical outcome of this research is an interactive dashboard that allows users to filter data on skills requested in any of the 52 countries and 37 disciplines across the world. Those considering a PhD or transferring a PhD to a different country might find this helpful.

We discovered that:

- PhD programs request transferable skills

- Skill demands vary significantly by country and discipline

- PhD expectations are rising over time

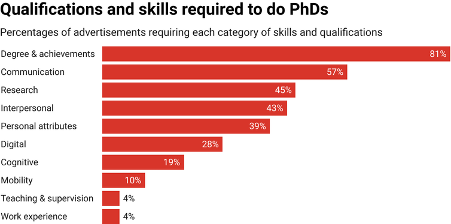

Most skills needed for a PhD are the so-called transferable skills wanted for post-PhD careers (skills that can be translated and applied to any professional context). The top 3 are:

- Communication – academic writing, presentation skills, speaking to policy and non-expert audiences

- Research – disciplinary expertise, data analysis, project management

- Interpersonal – leadership, networking, teamwork, conflict resolution.

Trending are Digital skills (information processing and visualisation) and Cognitive skills (abstract, critical and creative thinking and problem-solving).

Catch up on The Conversation article for more details.

Practical implications for PhD pathways and doctoral education

The limitations of job data research notwithstanding, the findings raise interesting implications for PhD pathways and doctoral education itself, for example:

Pre-doctoral education and research pathways:

We know research-based learning develops employability skills e.g. critical thinking, resilience and independence. Undergraduate and postgraduate degrees can further promote PhD readiness by embedding authentic hands-on research with academic or corporate partners, either as part of the curriculum or as extracurricular activities. Australasia’s very own Council for Undergraduate Research (ACUR), of which The University of Sydney is a member, works to support institutions and individuals in promoting and embedding research opportunities. Catch up on undergraduate research news from Australasia.

PhD program designers, managers, supervisors:

We need to keep a focus on the destination, on where the PhD and the candidate are heading to. Much training and learning relevant to any professional career are already offered to PhD candidates at this University but a disciplinary focus is valuable and PhD supervisors need guidance on how to support PhDs in career development, too. For some, accepting that your PhD student might not want an academic career after all or might change their mind halfway, might be a good start. More personalised skill development plans curated to individual needs and future ambitions might prove more effective although costly. And finally (and controversially), perhaps we should consider different assessment methods for PhDs. Complimentary or alternative assessments rather than the thesis alone might provide more suitable evidence (for academic and non-academic employers) of the learning and development PhD graduates have really gained. Examples like skill portfolios, reflective work, product or service design, solution proposals, or accounts of academic work and teaching efficacy, might demonstrate more rounded professionals for academic and non-academic work.

PhD candidates:

Be confident that you already bring a strong skill set for whatever career pathway you follow and gather evidence along the way. There are many research-based non-academic career opportunities to explore. Identify developmental opportunities in your research training to further develop your skills to suit non-academic jobs. If pursuing an academic career invest in teaching development, people and project management, and generally understanding how universities work and what academic work entails (it’s so much more than research). Supervisory meetings, peer conversations, and part-time work at university all provide great learning contexts.

Those keen to pursue a PhD no matter the challenges:

Provide strong evidence of transferable skills when applying for a PhD and check out our updated data dashboard for country and discipline specifics. Chances are you need to be flexible, resilient and adaptable to whatever turn your PhD takes and the professional opportunities that might open up.

Contact me if you wish to chat about this or share how this research might be helpful in your context.