It is hard to drive a car and simultaneously engage in a serious conversation for a P-plate driver, particularly when they need to steer a vehicle designed for right-hand traffic on a left-side road. It is similarly hard to lead a seminar and orchestrate bits and pieces of technologies for a teacher, particularly when they need to teach in the hybrid flexible (aka. HyFlex) mode in a classroom designed for teaching face-to-face.

Teaching in the HyFlex mode is challenging. As a learning scientist, I am tempted to refer to the theories of working memory capacity, multitasking, complex skill acquisition, and joint attention to explain why. But I am writing this post as a teacher who has been teaching hybrid courses in conventional face-to-face classrooms for a while. So, let me start by saying: ‘It is possible.’

For me, learning to teach in the hybrid mode has been not about becoming a superhuman teacher with unlimited working memory and capacities for multitasking but about learning to re-configure the teaching and learning environment and tasks in ways that scaffold me and engage students in teaching. As a wisely-planned trip and cooperative passengers could make your driving much easier, well-configured technologies, cleverly-organised activities, and cooperative students could make teaching in the hybrid mode manageable, even enjoyable.

Therefore, when I teach in the hybrid mode, I start by configuring physical and digital spaces and then redesign tasks. Here what I usually do.

Configuring physical space

If I constantly need to troubleshoot sound issues, move cameras, or worry that my laptop may run out of power, then teaching in the hybrid mode becomes a struggle. I try to get these issues out of my way before I start teaching.

- Knowing and configuring the space. I allocate 2-3 hours to go to the classroom, decide how I will arrange the space and set up technologies well before the first class. Do I know where I will locate cameras? Can I fix them in the correct position? Have I worked out how I will manage speakers and microphones during class discussions? Do my BYO devices work? There are a lot of details to go through, and initially, it is worth asking for assistance. However, eventually, I do everything myself and make sure I have not missed anything important, and technologies work as I expect. My biggest ‘oh rats’ moments were when I thought I knew but did not actually try.

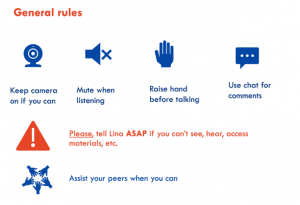

A simple slide featuring six classroom rules that help to make invisible issues visible. - Setting up technologies at the start of the class. I set up my BYO devices, login, adjust cameras, and prepare physical and digital spaces for teaching at least 20 minutes before each class. It is hard to do this on the go while interacting with the students. If I cannot get into the classroom earlier (e.g., I teach somewhere else or somebody else teaches in the classroom), I try to set a reoccurring task that keeps the students engaged for the first 15-20 minutes and allows me to prepare. My tasks are usually simple, such as: “Create 2-3 joint slides with your main takeaways from weekly readings” or “List your ‘muddiest points’ in a shared Padlet and select three most important”. Once I am ready, I build on what the students have done already, consolidate, and move on.

- Creating a warning system that makes invisible issues visible. When teaching in the hybrid mode, it is easy to lose sound or internet connection and keep going without noticing the problem for a while. The main challenge is to become aware of these issues as soon as they appear. My typical strategy is to ask students for assistance. A single slide like the one on the right usually helps me get them on board. Sometimes I also ask 1-2 specific students in the face-to-face class to monitor the online space and warn me if there are any issues. A combination of such simple social strategies usually results in a robust ‘warning system’.

Configuring digital space

The need to orchestrate digital tools and resources adds a number of extra tasks. Have I switched on recording? Can students hear me? Has everyone downloaded worksheets? It is easy to forget small but essential things that affect everyone’s experiences. It is even harder to create a shared situational awareness among students across the two spaces. My main strategy is to design the digital space in a way that keeps students and me on the same page, minimises my cognitive load, and simplifies coordination.

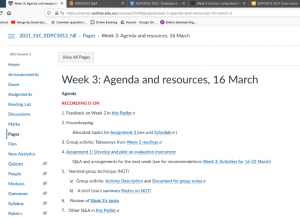

- Creating tools for shared situational awareness. As pilots use checklists to ensure that the crew is on the same page and the plane is properly configured for flight, I create similar scaffolds for myself and my students. For this purpose, I typically use a seminar agenda, but also list on it things that I tend to forget – see an example in the image to the right. I literally keep everything and everyone on the same page by holding the agenda and all seminar resources together and shared with the students. This allows me to offload a number of simple, practical things out of my mind and focus on more demanding teaching tasks. Simultaneously, a single-entry point with access to relevant resources helps reduce students’ confusion and enables them to catch up independently even if they get disconnected or have other technical issues.

- Minimising switching between applications. Those who have been teaching remote courses know that most tasks and interactions take longer in the online space. One of the time-eaters is the need to switch constantly between various resources and applications: now a Word document, now PowerPoint slides, now a Padlet, etc. I usually try to minimise this by using only web applications and preparing the digital space in a single web browser. It requires a few minutes to upload all slides and documents and open them in different tabs before class, but it takes only a blink to switch between them when teaching.

Configuring tasks

Designing learning tasks that work seamlessly across online and face to face spaces is the most challenging part of hybrid teaching. It is easy to give a lecture but much more demanding to coordinate interaction across the spaces when students engage in discussions or work in groups. My primary strategy is to share the ownership of knowledge and responsibility for orchestrating learning activities with students.

- Giving students agency to ‘complete’ imperfectly-designed tasks. Learning tasks are never perfect: students will always do some things differently than you intended, and you will not always notice that they got stuck or misunderstood instructions. Teaching in the hybrid mode taught me to be less concerned about spelling out all task details but instead give more intellectual agency to the students and focus on helping them learn from their experiences and mistakes. For example, during group work, I ask the students not to wait for my guidance but instead come up with their own decisions on how they could solve problems and do things in the hybrid mode. Even if the students do not get certain things right, their mistakes allow me to identify the most complex aspects and explain them well. Learning from mistakes, if well-designed, could be as productive as learning from correct solutions. One of my strategies to engage students in deep thinking is to discuss with students their decisions and reasons for doing certain things in a particular way. We also discuss how this could be done differently in other situations that they may face in future. Sometimes, I ask students to put on a teacher’s hat and discuss how they would change the task if they had to teach a similar skill or concept to their peers or work colleagues.

- Designing for student-led teaching. Learning-by-teaching is generally known as an effective pedagogical approach that enhances students’ engagement and academic outcomes. So, I do not avoid giving students tasks and assessments that involve teaching. Peer-led seminars and peer-tutoring are among them. For example, I ask the student groups to lead short, interactive hybrid seminars that combine presentations and learning activities for their peers. Students also moderate asynchronous discussions and lead seminars exploring issues from weekly readings. Such peer-to-peer activities create opportunities for the students to get an insider view into hybrid teaching, appreciate its complexities, and share responsibility. Of course, I need to help them out manage technologies and make sure the key ideas are understood and consolidated. However, student-led tasks allow students to own what they are doing and share with me some work on the front stage.

- Co-constructing joint digital artefacts. Tasks that require students to interact with each other and co-create shared knowledge artefacts (e.g., plans, maps, outlines, reports) have many pedagogical benefits. In the hybrid classes, this strategy, combined with asynchronous technologies (e.g., Google Docs, Padlets), is particularly handy. One of the best ways is to embed various joint digital artefacts in tasks that students do asynchronously. For example, I ask the students to annotate papers, create joint concept maps as they do their weekly readings, provide peer feedback on assessments, and work jointly on larger projects that require progressive engagement. If the students continue building on the same artefacts during their classes, the use of technologies and interaction among the students who attend face-to-face and remotely become almost seamless.

Of course, I do many other things to make hybrid teaching and learning possible and meaningful for students, but my main principles are two; firstly, I try to configure the hybrid environment in ways that scaffold my teaching and, secondly, I share the ownership of knowledge and responsibility for orchestrating learning activities with students. When the environment and students scaffold my teaching, then I can scaffold students’ learning.

3 Comments