Work-integrated learning (WIL) is essential in professional health education, but it doesn’t always prepare students well for real practice. In pharmacy education, students traditionally completed just a handful of workplace activities, often late in their degree. They often involved observation rather than active engagement, resulting in missed opportunities to connect classroom learning with the realities of professional practice.

When we introduced our new Bachelor of Pharmacy (Hons)/Master of Pharmacy Practice program in 2023, we saw a chance to change this. We wanted work-integrated learning woven throughout the degree, starting earlier and offering more varied, authentic experiences. One innovation we introduced was ‘mystery shopping’ – where second-year students visit community pharmacies as simulated patients seeking advice on common health concerns.

Below, we share how we developed this activity for 270 students, what we learned, and how we’ve refined it based on student feedback.

What is mystery shopping in pharmacy education?

Mystery shopping flips the usual learning perspective. Instead of students shadowing pharmacists, they enter pharmacies as patients with specific health concerns – perhaps needing advice about hay fever, sleep problems, or skin conditions. They interact with pharmacy staff just like any customer would, then reflect on what they observed.

The educational power comes from experiencing healthcare from the patient’s viewpoint. Students see how pharmacists communicate, problem-solve, and provide care in real-time. It’s learning through experience rather than textbooks or observation.

Mystery shopping has been used in small, opt-in pharmacy projects with students before, such as here, here and here. However, we wanted to make it a core part of our second-year curriculum – making this authentic learning experience available to all students.

Connecting classroom learning with real-world practice

We introduced mystery shopping into our second-year Pharmaceutics and Professional Practice unit, focusing on a critical skill: advising patients on over-the-counter medicines and common health concerns like allergic rhinitis, eye and ear health, dental issues, skin conditions, and sleep problems.

This is core work for community pharmacists. Over 80% of adults and 40% of children use over-the-counter medicines monthly. Yet newly graduated pharmacists often feel underprepared for these everyday interactions – partly because they haven’t had enough structured practice in this area.

Mystery shopping lets students connect their classroom learning about these conditions with real pharmacy practice. They see how pharmacists actually communicate treatment advice, ask questions, and make recommendations. Experiencing this from the patient’s perspective builds both knowledge and confidence for their future roles.

Designing the activity for 270 students

When we first ran this activity in semester 1, 2024, we had 270 students to coordinate. We needed the activity to be structured enough for consistency, but flexible enough for authentic learning experiences.

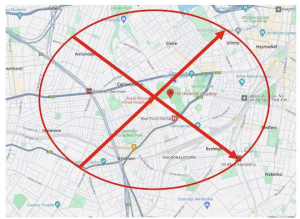

Students worked in pairs, alternating between being the “patient” and the observer. Each pair completed four pharmacy visits across the semester, covering different health scenarios. To prevent overwhelming pharmacies near campus – and to expose students to diverse practice settings – we created an exclusion zone around the university, encouraging students to visit different types of pharmacies across Sydney.

We supported students with briefing videos from an international expert in mystery shopping, communication skills training, clear step-by-step Canvas instructions, and a guided reflection tool. After each visit, students recorded video blogs capturing their immediate observations. At semester’s end, they completed a reflective statement synthesising their experiences.

Across the semester, students completed 536 pharmacy visits.

What did the students think?

Student responses gave us valuable insights. Positively, 38% of students identified mystery shopping as one of the best aspects of the unit. They appreciated seeing real pharmacy practice and strengthening their knowledge of over-the-counter medicines, found the activity engaging and creative and valued building both knowledge and confidence:

The MYSSA activity was so much fun… I could see many different things and learn by meeting different pharmacists

The mystery shopping did help me gain some useful knowledge and learn some interesting insights

Conversely, we also heard clear concerns. Some students felt four visits were too much in an already packed semester and wanted more feedback between visits. Others felt uncomfortable with aspects of the experience – whether it was observing practice that differed from what they’d learned in class, or worrying about taking time away from real patients:

Mystery shops were good opportunities for learning, but I found it a little uncomfortable to fake being a patient and taking time away from real pharmacists

Behind the scenes, we also found the activity created significant workload for staff – allocating pairs, managing Canvas project teams, and resolving issues. The timing meant pharmacy practice staff had limited availability to support students when problems arose.

This feedback showed that the activity had real value, but we needed to streamline it and provide better support.

What we changed (and why it worked better)

Based on what students told us, we made several key adjustments for 2025:

We reduced the workload. Four visits became two, with better alignment to the unit schedule. This addressed the “too much to do” feedback while keeping the core learning intact.

We improved ongoing support. Instead of students forming pairs in rotating lab groups, they now paired up in weekly tutorials. This gave pharmacy practice staff consistent contact with students throughout the semester, making it easier to address concerns as they arose.

We built in more feedback opportunities. This was the big change. Students now submit their roleplay plan before each visit, then their video blog afterward. They receive feedback from both peers (using Canvas peer review) and tutors. The peer review also meant students experienced more pharmacy visits vicariously – learning from each other’s observations without additional visits. We also added an end-of-semester debrief where students could compare experiences and discuss any concerns with tutors and peers.

We simplified the reflection process. After some students lost their work in the HP5 reflection tool, we switched to Canvas submission with structured reflection questions.

The results were very positive and we were impressed by the quality of students’ video blogs and the thoughtful peer feedback:

Overall, the vlog’s structure is very clear… both the observer and those participating offer useful contributions to the discourse. Very good job guys 🙂

One tutor shared:

I would like to take a moment to share one of the group vlogs, it is really good! These students are full of energy, and they have found it very useful for their learning. Vlogs like these are so refreshing and motivates me to keep teaching.

Most tellingly, we received far fewer complaints about workload in 2025 student feedback, suggesting our changes hit the mark.

Want to try something like this in your own teaching?

Mystery shopping isn’t just for pharmacy. The core principle – students experiencing professional practice from the client or patient perspective – can work across health disciplines and beyond.

If you’re considering a similar activity, here’s what we learned matters most:

Start with clear structure, then allow flexibility. Students need briefings, communication skills training, and step-by-step guidance. But within that structure, let them design their own scenarios and choose where to visit. The authenticity comes from real, varied experiences.

Build in multiple feedback points. Our biggest improvement was adding peer review and tutor feedback throughout, not just at the end. Students learn from each other’s experiences, and ongoing feedback helps them process what they’re observing – especially when they see practice that surprises or concerns them.

Consider workload carefully. We learned that fewer, well-supported experiences was better than more activities in an overcrowded semester. Quality over quantity.

Plan for student support. Some students will observe things that make them uncomfortable – practice that differs from teaching, or ethical grey areas. Regular touchpoints with teaching staff and end-of-semester debriefs create space for students to discuss these experiences.

Think about logistics early. For us, this meant preventing pharmacy overload near campus and ensuring teaching staff were available when students needed support. For other disciplines, consider what equivalent planning makes sense.

The activity works because it builds empathy alongside professional knowledge. Students don’t just learn what pharmacists do – they experience what it feels like to be on the receiving end of care.

Key lessons and where to next

Three things stand out from our experience developing this activity:

Iteration matters. Our first version was good but imperfect. Student feedback and our own reflections led to simple modifications that significantly improved both student and teacher satisfaction. Ongoing evaluation from multiple perspectives – students, staff, and our own teaching practice – was essential.

Authentic workplace experiences at scale are possible. With 270 students completing over 500 pharmacy visits, we demonstrated that work-integrated learning doesn’t have to be small-scale or opt-in. Careful design and willingness to adjust makes it feasible for large cohorts.

The patient perspective is powerful. Mystery shopping fostered empathy and professional identity in ways traditional observation might not. Experiencing healthcare as a consumer offers valuable learning opportunities across health professions – potentially beyond.

We’re continuing to refine and research this activity. We recently received a Work-Integrated Learning Australia research grant to formally evaluate the experience through student focus groups. We’ll explore how mystery shopping impacts learning, connects with other unit activities, and influences interactions with pharmacy staff. We’re particularly interested in understanding the student experience more deeply and identifying further improvements.

We look forward to sharing our results and further improving the activity!