Imagine: It is week one of the semester, and the classroom is buzzing with students eager to engage and learn. In small group activities, students discuss ideas and work on set problems. There is a shared sense of enthusiasm. Fast-forward several weeks. The energy is tangibly different. It seems many groups are disengaged and distracted, and consequently, learning outcomes are suffering.

What happened?

How can we address diminishing engagement with in-class small group activities as the semester unfolds? Students naturally sit with the same people each week, so we developed a simple yet powerful initiative to break this ‘habit’. It resulted in improved engagement and a sense of belonging within the class.

In the group work I made friends and picked up new communicating/teamworking skills

What’s going on with group activities?

Working effectively with others and navigating different opinions are important employability skills acknowledged through the University’s Graduate Qualities of interdisciplinary effectiveness and influence. Working with the same group of individuals can cause ‘group think’, dissipated groups, and ‘social loafing’.

How did we fix group activities?

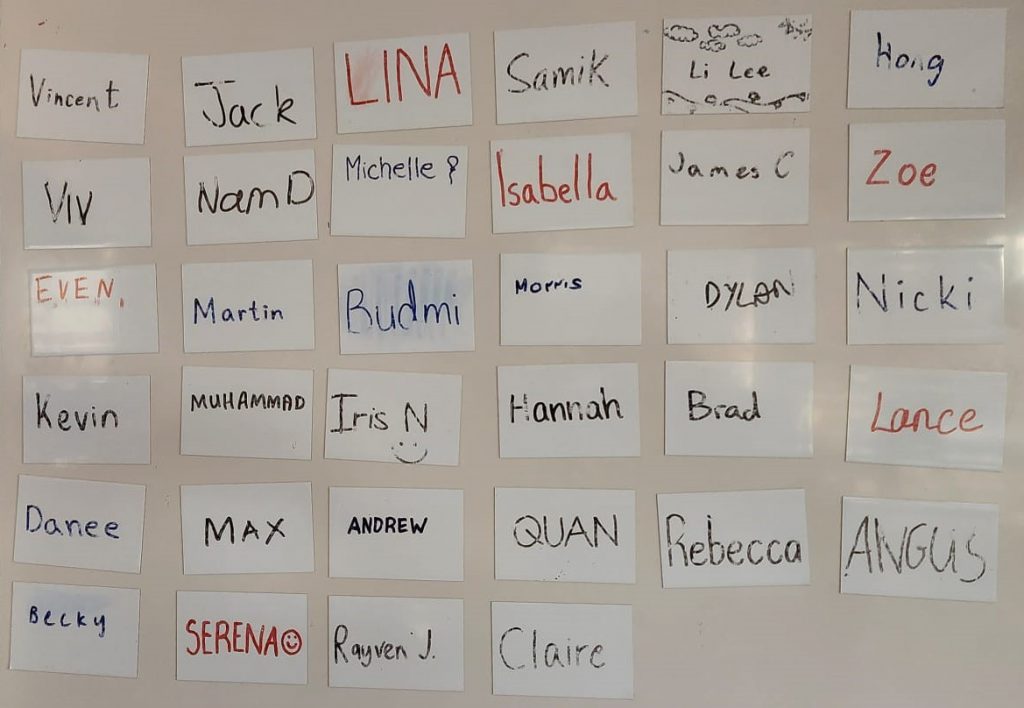

We introduced ‘name magnets’ to continually randomise in-class activity groups and allow students to comfortably move groups each week. This approach closely aligns with Deibel’s (2005) work, which highlights that instructor-assigned groups are optimal in ephemeral in-class group activities.

At the beginning of the semester, every student wrote their name on a 10 x 15cm whiteboard ‘Name magnet’. In week one, students self-selected groups. From week two, their instructor assigned a randomised group for that week by placing the ‘name magnets’ on the classroom whiteboard.

Magnets are cost-effective and can be purchased in bulk for just over $1 apiece, but paper name tents or name tags could be used as an alternative.

What did we notice?

We were surprised that by week 3, students were keen to actively discover their groups. As the semester progressed, students reported improved communication skills and their ability to express their ideas to diverse audiences.

One student commented in an unsolicited email, “In the beginning, I was afraid to speak due to my poor language skills and feared my idea might sound stupid. But everyone was nice enough to listen to me and none of them taunted me, even when I made common sense mistakes… Both my communication and interpersonal skills have significantly increased.“

The teaching teams and students highlighted that student engagement in activities tended to be more sustained throughout the semester. Each week, the groups have a different energy and vibrancy. A student commented in the 2023 unit of study survey, “I like the idea of randomising students during class discussions because it opens up different views and perspectives to approach the problems.”

Both teaching teams and students reported an increased ability to learn the class’s names. Another student commented in the 2019 unit of study survey, “Weekly discussion with different teammates is the best part to me. I really learn a lot from my peers and have chances to make good friends.”

Peer learning and student belonging

What is striking about this student feedback is not only the self-reported benefits of different soft/core skills but also the theme of belonging due to peer learning. Here are some examples:

- “The classroom setting I experienced had a profound impact on my learning. Weekly collaborative tasks with different peers promoted teamwork, diverse perspectives, and enhanced understanding of complex concepts.”

- “It was a good challenge to continually be involved within changing groups every week for different learning activities. It was great to learn and bounce back ideas from others within a group discussion.”

Contemporary higher education literature underlines the importance of belonging and peer learning in students’ tertiary education successes. Following the thread, other research shows that a sense of belonging is highest in classes where educators learn students’ names and encourage students to participate. Others also highlight that to be behaviourally engaged, a student needs to be cognitively engaged, and for this to happen, they must first feel emotionally engaged and safe.

We have found that the fresh faces and new social interactions the ‘Name Magnet’ approach delivers provides greater interaction, peer learning, and a sense of belonging, thereby promoting ongoing engagement in our workshops.