Embedding equity and inclusivity into the curriculum can be challenging. Amani Bell from Work Integrated Learning in the Sydney School of Health Sciences (SSHS) recently had a Zoom conversation with Celine Diaz from the discipline of Occupational Therapy in SSHS, to discuss how Celine is bringing this about in a new unit of study.

Amani Bell: I’d love to hear about what you’re doing in your unit of study, how it started out.

Celine Diaz: The Bachelor of Applied Sciences (Occupational Therapy) program underwent curriculum review, going back a couple of years now. In this new program, we integrated the Disability and Participation stream as a major or minor, and its roll out began in 2020. This year we have our first cohort of occupational therapy students coming through as first years in the new undergraduate program. This particular unit of study is a 2000-level unit, where we currently have a smaller group of non-standard occupational therapy students and other students who are doing this as an elective or part of the major.

With the NDIS (National Disability Insurance Scheme) becoming the main way that people with disabilities access services, we felt that we had to prepare our students a different way. There are now a lot more ‘non-traditional’ types of roles for occupational therapists. Twenty years ago, when I was going through uni, there was a very clinical and health focus, and lots of people got jobs with NSW Health. Nowadays, it’s moving more into the disability sector, where there are many practitioner organisations that rely on NDIS funding.

Having the Disability and Participation major as part of the new curriculum for the undergraduate program is a national first for occupational therapy degree programs. Historically in occupational therapy, we have tended to have a bit of a bias towards working in the context of health care, which can sometimes overlook discussing working in the disability sector. With this stream, we’re trying to think more broadly about the issues around disability.

Historically in occupational therapy, we have tended to have a bit of a bias towards working in the context of health care, which can sometimes overlook discussing working in the disability sector. With this stream, we’re trying to think more broadly about the issues around disability.

In our previous degree program, final year students did a unit that focused on community and population-level intervention, that covered cultural competence and Indigenous ways of knowing and being. We often found that it was a lot to put onto the students at the end of their degree when they’ve been mostly focused on more positivist kinds of approaches, individual interventions and clinical settings. For the last year to suddenly present – ‘here’s at a whole other way of thinking and here’s a whole other way of practicing’ – the students often find it challenging to wrap their heads around, especially because they’ve already been on most of their placements. It was a real mind shift for many of them.

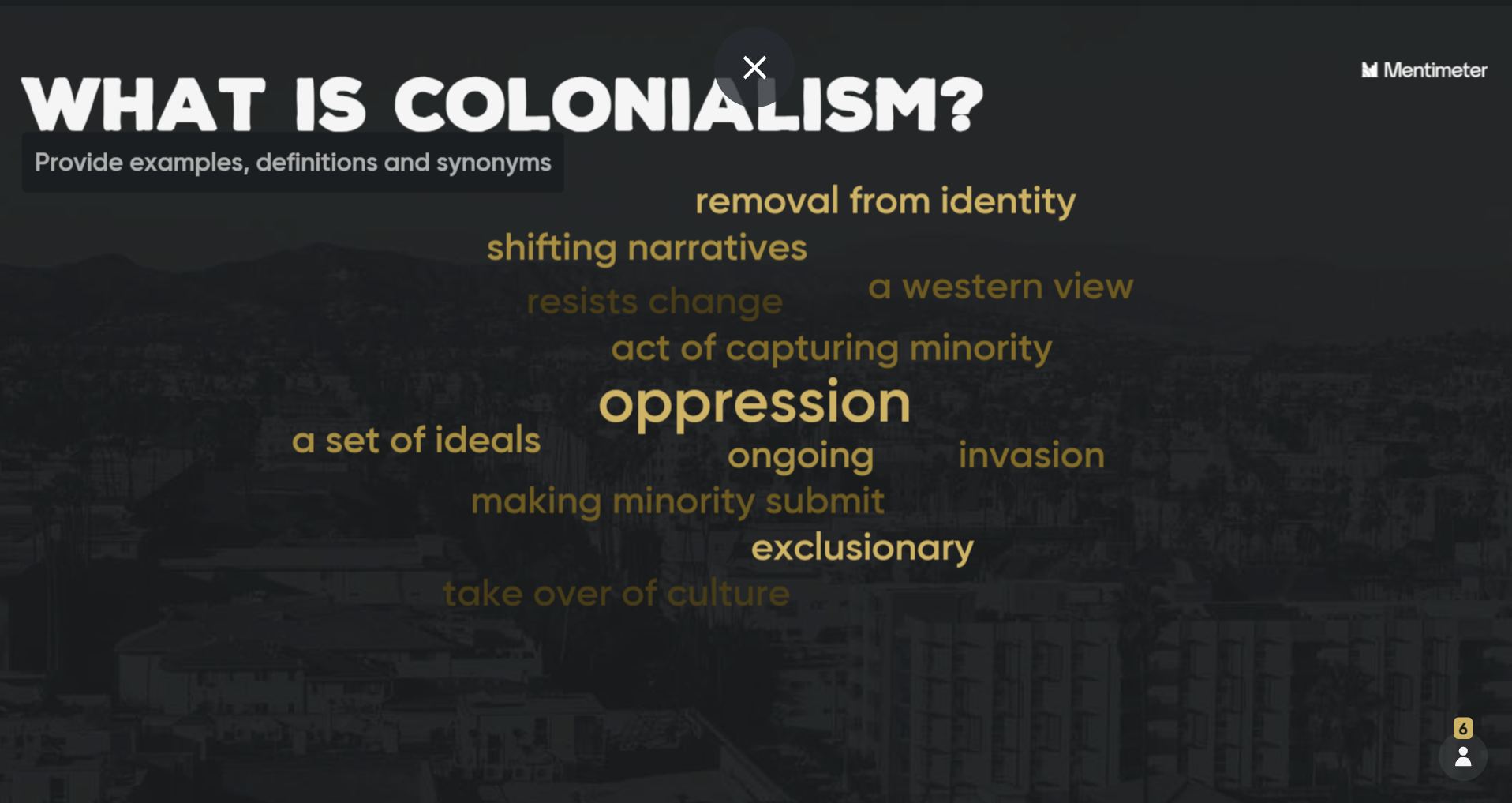

One of the things that we’ve really taken the opportunity with this new program is to embed cultural capability and learning about Aboriginal history, but also equity in terms of health, across culture, race, ability, right from the very beginning of the degree. Many of the Disability and Participation units do that in different ways. The one I’m coordinating is called Disability and Decolonising Practices. The students learn about colonisation in the first five weeks, from the eyes of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people, from the eyes of European settlers, and what we think of that today. But of course, more than that, we say colonisation is not just an event, it’s an approach that still happens when we’re talking about power and oppression of people that have been historically marginalised. And so we apply that thinking to people with disabilities, that they are also colonised in this way.

…we’ve really taken the opportunity with this new program is to embed cultural capability and learning about Aboriginal history, but also equity in terms of health, across culture, race, ability, right from the very beginning of the degree.

Amani: So the idea is that they’re encountering these concepts early on in their degree so that they’re better prepared for placements and their eventual practice?

Celine: Exactly. In our new program, students don’t do placement until their second year. Because they’ve been enrolled in preceding Disability and Participation units of study, I’ve noticed a difference already. They have a really different way of thinking, we can see them thinking more broadly and with a more critical lens.

…I’ve noticed a difference already. They have a really different way of thinking, we can see them thinking more broadly and with a more critical lens.

Amani: I imagine all of the teaching is online at the moment?

Celine: Yes. We have asynchronous (pre-recorded) 1-hour lectures and 2-hour live remote tutorials. As the coordinator, I facilitate regular guest educators, the majority of which are our Aboriginal colleagues. We usually spend the first hour having a bit of a yarn. Yarning has an open structure, and it aims to reduce power differentials. In collaborating together to plan these live classes, we were concerned about whether we’d be able to achieve it remotely, but it went well, I think because I invested time in the first two weeks building a supportive group dynamic, making sure that everybody felt safe and heard. In week 1, we had a Padlet where students could design something about themselves, put up pictures that they wanted to share. I made an example one that had emojis as bullet points, and a photo of my kids in the local park. It was a way of setting up the space to show ‘I’m learning alongside you’. As a teaching team, we agreed that we were facilitators. We don’t see ourselves as having all the answers or being experts, but we see ourselves doing our best to learn more, and to push ourselves forward alongside the students.

Amani: Could you give an example of a learning activity in the unit?

Celine: A really big part of this unit of study is critical reflection. We’ve drawn on the national Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Curriculum Framework which has a set of five graduate cultural capabilities. One cultural capability is reflection. For the first seven weeks of the semester, we have the students writing short reflections in response to preparatory material such as readings, videos and modules. They also participate in a critical reflection workshop in week two, which is something that Josephine Gwynn has designed as part of a teaching and learning grant. Discussion and practice of how critical reflection and reflexivity involve developing a reflective practice when it comes to being a practitioner is woven throughout the unit of study. We also have to be mindful that not everybody who does this particular unit of study is a health student since it is an interprofessional unit that is open to anybody, therefore we have some people who are doing arts and we expect that we’ll have people doing design or architecture, you know, all sorts of disciplines.

The students write short, critical reflections (250 words) for seven weeks and then they have to choose one of the weekly reflective topics and expand on it in a longer paper (1500 words). Some of the students needed a bit of extra support to learn how to develop a reflexive argument, how to include their voice in it, because it’s all about unpacking their positionality in response to the source material. Speaking with their own voice is definitely something I’ve seen them develop. Students have told me that writing this paper is the point it all starts to come together – that this unit of study involves your mind, but it also involves your heart and your hands. That there are different ways of knowing, being and doing.

In the beginning, when we were saying – ‘you’ll have an emotional reaction to the material – expect that and make space for it. Write about it and discuss it with people if you want to’ – I don’t think the students really experienced that till the middle of semester. At this point, they were able to share with each other and with me that ‘Yeah, I’m starting to feel that now. And this is a lot to process and it’s impacting the way I see everything else. It’s changing my worldview.’ One of the students said, ‘I feel like we have to rewire our brains’. To which I resound, ‘Yes, you literally do. From a neuroscientific perspective, you’re making new pathways when you’re seeing things in a different way’.

One of the students said, ‘I feel like we have to rewire our brains’. To which I resound, ‘Yes, you literally do. From a neuroscientific perspective, you’re making new pathways when you’re seeing things in a different way’.

The second assessment is something a bit more challenging, where we get them to apply and analyse what they’ve been learning. The students will look at a Reconciliation Action Plan and a disability action plan of an organisation with a decolonial lens or framework and write a 2000-word report appraising and critiquing elements of it. At the end of the unit, the aim is for the students to feel like they’ve really applied what they’ve been learning, and they’ve come up with something that shows them, ‘I can do this, and I can see how it relates to when I go out and practice. I have a constructive way of being able to see things with a decolonial framework and critical lens.’

Amani: It must be so encouraging and exciting to see the students develop from the beginning where it’s all really unknown to them and then saying things like ‘I see things differently now’. I mean, that’s what education is all about, isn’t it?

Celine: It really is. In the first couple of weeks, a lot of the students were reflecting on ‘Oh, I didn’t learn about all of this history, this is not the same history that I learned in school. We only learned bits of it.’ To truly hear about pre-colonial history and the full truth of the violence of colonial history makes it rather confronting material, but is an important foundation for truth-telling.

As we moved on by looking at identities as intersectional and having students look at their own identities as intersectional, then considering their own positionality, how they could be involved in advocacy and allyship -I think that’s when they really started to have more of that emotional reaction and also start to unpack their worldviews.

Amani: What, if anything, would you change about it the next time you teach this? You said you’re hoping more students will do the unit next year.

Celine: Yes, I think it’s going to be very interesting. The first challenge is how we will do it for a group of 100 or more students. A lot of the reflection and the work that really drives students to make changes either in their thinking or in their practice happens in the setting of a smaller group. For this reason, we want to keep tutorial groups down at no more than 20 and make sure that the tutors who lead these tutorial groups understand the ethos of this unit of study. It’s also essential to have people with lived experience on the teaching team, for example, First Nations people, people with disability, people of colour and so on.

The other challenge is using different types of assessments. For example, to have some of the weekly critical reflections be something other than written pieces of work. We want to open it up for poetry or music or art pieces that are submitted with shorter abstracts. These methods have been the way that knowledge has been passed on for millennia. Because we are in a university setting, we do need certain outputs and learning objectives, but we need to make space for non-traditional outputs.

Amani: Is there anything you wanted to add?

Celine: We have had a few people who have contributed to the unit of study and I want to acknowledge them, and how it wouldn’t be what it is without them presently and we certainly need them and others going forward. Of particular importance is the involvement of our Aboriginal colleagues – Rodney Adams, Sheelagh Daniels-Mayes and John Gilroy. We’ve also had disability rights educator Jax Jacki Brown. Chontel Gibson was the person who proposed this unit of study and designed its overall structure and existing learning objectives. Kim Bulkeley and Josephine Gwynn have also played key roles in developing the thinking behind this unit. Part of having a decolonial approach is that teaching is a collective effort, with different people coming at it from different perspectives. We talk a lot about diversity and intersectionality in this unit of study, and the students see this in action as they are taught by people who are diverse and have complex intersectional identities.

In that collective working together, we are doing a lot of critical reflection ourselves. Thinking about it, it’s kind of ironic that we want to talk about disability and decolonising practices within a university. But I think that’s also because we are dreamers. What we have in common is that we’re able to dream about a future for our students and for ourselves that’s more open, more equitable and more diverse. And that starts with our teaching practices.

Want to know more?

If you would like to know more, please contact [email protected]