In this extended piece for Teaching@Sydney, Julia Kindt, Associate Professor in the Department of Classics and Ancient History in the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, responds to Professor Dirk Moses’s experience on flipping the classroom.

As Dirk Moses and others have observed, traditional lectures have fallen out of fashion. Straightening out the crumpled lecture script from the year before, appearing at the lectern at the top of the hour and lapsing into an hour-long monologue – all while ignoring the audience as much as possible – no longer cuts it. That is, if there still is an audience, given the plummeting attendance rates.

These days, both students and lecturers expect more. Experience teaches us that learning is more likely to happen through a conversation between teacher and student, while educational studies continue to show that interaction is important for learning. By making classes more interactive, we compel students to engage actively with the material presented, to think things through, and to frame their own positions – and to do so continuously throughout the semester, rather than as a one-off for the essay or exam.

Interactive or conversational teaching finds its obvious home in the seminar or tutorial setting. Yet, where does this leave large lecture courses?

In his article, Dirk recounts giving up the traditional lecture format altogether in favour of a teaching style focussed on discussion and group work. In an interesting, brutally honest, and often hilarious read, he details the challenges and opportunities that ‘flipping the classroom’ entails and reports on the mixed results. Apparently, about half of the students loved it and took advantage of the obvious opportunities this form of teaching affords; the other half seemed either ambivalent or outright unimpressed. One of the challenges in making sense of flipped classrooms in higher education is that it is not a uniform topic. Just like traditional lectures, flipped classrooms can be good and bad, and can vary in their pedagogy and implementation.

as with most things in life, the ideal state may lie in some sort of compromise between extremes […] the traditional lecture, combined with more interactive forms of teaching may strike just the right balance

Yet, as with most things in life, the ideal state may lie in some sort of compromise between extremes. As Dirk himself concludes, the traditional lecture (minus the crumpled notes) still has something to offer. Combined with more interactive forms of teaching it may strike just the right balance by providing and framing information on the one hand, and turning it into a dynamic medium for active thinking on the other.

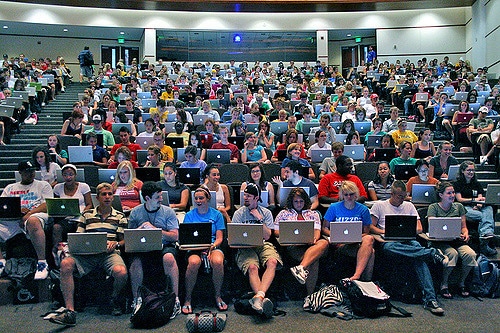

In this article I relate some strategies from my own teaching practice for how interactive teaching can work in large lecture courses. During my ten years of teaching at Sydney I have rarely fully flipped the classroom. But most, if not all, of my lectures involve interactive elements. Based on size of the student cohort, subject matter, and level of prior knowledge, I tried out a number of interactive teaching styles that intersect with traditional modes of delivery.

A typical lecture – Combining lecturing with interactive elements

In all my units of study, I chose the traditional (frontal) lecture format to introduce the topic, set up expectations, and frame the interactive elements. Most of my lectures start with 15-20 minutes of traditional lecturing supported by PowerPoint to prepare the ground for subsequent discussions and group exercises. This ensures that everybody is on the same page and that the discussions remain focussed and productive. I usually follow this with up to three exercises/discussion points as well as more information presented in the traditional format.

1. Early on – knowing where are your students are at…

Early on, I gauge where the students stand with regard to the main topic. Sometimes this takes the form of an open question regarding that week’s content. Alternatively, I set a problem and ask them to raise their hands if this reflects their experience or ask whether they have encountered something similar before, and in what context. This brings the students’ experience into the lecture and uses their knowledge as a springboard into the topic. Experience and expectations are aligned for both students and the teacher.

2. Structuring the Class – make it clear where we are and where we are going…

CC BY-NC 2.0 flic.kr/p/eZCpH

All my lectures have a clear structure communicated via PowerPoint slides. This is important for guiding the group discussions and exercises. At no time during the lecture is there uncertainty as to where we are and where we are going. If there is a whiteboard in the lecture theatre, I use it to take notes during the group discussions.

3. Integrating Activities

About 15 to 20 minutes into the lecture I break for the first exercise. This can be a source, a set problem, or some form of quiz. Exercises work best when supported by some documentation – a text, an image, an artefact or video the students have in front of them – to provide common ground for discussion. I always pause for a few minutes, giving students time to engage with the material on their own before we share our ideas. Sometimes I add questions to jumpstart their thinking. What are the major themes in this source? What is at stake here? Can you identify three issues with this text or image?

On occasion I have used this format to share genuine research questions with the students: ‘The following is an unresolved problem relating to this lecture that continues to bug me. Perhaps you know the answer?’ Almost inevitably, this results in a flood of emails the same afternoon with possible solutions. The passive recipients of knowledge have become active thinkers and researchers in their own right. And one never knows what students will come up with: on several occasions, the conversation has yielded fresh insights.

4. Setting a Goal or Purpose

Interactive lectures work best if the lecturer makes clear announcements with regard to the purpose of a given session as well as some concluding remarks. Before I run my ‘Five things to take from this lecture’ slides as a form of conclusion, I give the students a few minutes and ask them to write down their own five points. As well as letting them think back on the content, it provides me invaluable feedback about what the students actually took from the lectures and discussions.

Tools, technologies and teaching approaches

The following tools and arrangements support the interactive teaching style. While none of my units employ all of these at the same time, I generally combine some within each unit.

The Online Reading Journal

In his article, Dirk points to a common problem of the flipped classroom: lack of student preparation. While interactive teaching requires students to do pre-work in order to be successful, students do not always come prepared, making productive, communal discussion difficult. To address this, I set up an online reading journal. Students must post five extended bullet points on the readings prior to the lecture each week. These can be questions, comments, and observations – with the sole requirement that the journal reflect the student’s having done the entire reading, not just the first two pages.

In his article, Dirk points to a common problem of the flipped classroom: lack of student preparation. While interactive teaching requires students to do pre-work in order to be successful, students do not always come prepared, making productive, communal discussion difficult. To address this, I set up an online reading journal. Students must post five extended bullet points on the readings prior to the lecture each week. These can be questions, comments, and observations – with the sole requirement that the journal reflect the student’s having done the entire reading, not just the first two pages.

In units where I used this setup, well over 90% of all students posted each week. Lecture discussions were lively, informed, and productive. Lecture attendance also increased, with students keen to find out what the lecturer and their peers had to say about the readings.

Students receive feedback on their online reading journal twice during the semester: first after six postings (in week 7) – giving them early feedback – and then again after the last posting. This assessment replaces the traditional mid-term exam, so the overall marking load remains roughly the same.

An additional benefit of the online reading journal is that it can be accessed before each lecture to identify what students are picking up from the readings. This provides invaluable feedback about student progress that can be incorporated into subsequent lectures and discussions. Each lecture explicitly addresses some of the questions, problems, and concerns the students raise online. This further highlights the genuine and ongoing conversation between students and lecturer.

The Online Discussion Board

Some of my units feature an online discussion board providing an opportunity to continue the lecture and tutorial discussions beyond the classroom and outside appointed times. The board is set up in a way that reflects the overall structure of the unit and the topics of the individual weeks. I usually post a question or two each week to get the discussion going, or I refer students to the online discussion if we run out of time to discuss things during the lectures or tutorials. It works particularly well in units which revolve around genuinely controversial topics. Posting in the online discussion board counts towards tutorial participation. Shyer students in particular have found this feature helpful; and in some cases, this has significantly improved their involvement in the unit.

Bringing Research (and Smartphones) into the Lecture

While I found initially found the increasing presence of laptops, tablets and smartphones to be annoying, I now tend to draw on the possibilities that this technology offers. I frequently challenge students to use their devices to to seek out information during our group discussions and to report back to the class as a whole. In one case, students even rang an outside expert during the lecture (‘Hi! This is Sydney Uni calling from a lecture on…’). Rather than distracting from the subject at hand, the use of the electronics furthered engagement and interaction.

Tutorials Before the Lectures

Sometimes it can be a good idea to schedule tutorials before the weekly lecture. This can work well in units where the themes of the lectures and tutorials are particularly closely aligned. The students can discuss the material first in the tutorial setting. They may then be more inclined to attend the lectures later that week, to find out what the lecturer makes of the same material.

Letting Students Write an Assignment on a Title or Topic of their own Choice

In some 3000-level units, I offer students the choice either to write about a set question or to come up with an essay topic of their choice – closely related to the course content. The only condition is that they stop by during office hours to run the question by me before they get started to check feasibility and avoid cases of plagiarism.

This helps students to learn how to identify meaningful research questions on their own and to choose and investigate something they really care about. It also supports the interactive teaching style since many research projects the students tackle emerge from the group discussions and interactive elements in the lectures.

About 20% of all students seize this opportunity. Over the past ten years this has generated numerous wonderful essays that absolutely blew my mind. In many cases, these students stayed on to expand their topics into an honours thesis or M.Phil in a subsequent semester. This has also enhanced my interaction with students: my office hours are often packed with those who want to discuss their essay topics – often more than once. To manage the extra workload it is important that these essay consultations be kept to focussed, ten-minute slots. Personally, I find it worth it.

Teaching Outside the Classroom

About once a semester, we leave the lecture theatre to explore the topic outside. The Nicholson Museum, the archaeology showroom, and the storerooms of the Macleay Museum have all been destinations. Students love these ‘adventures’. It encourages them to apply what they have learnt in the lecture theatre to new contexts.

‘The Outside’, Inside the Classroom

CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

I have also encouraged students to bring material objects into the classroom. For example, in a unit on historiography, we spent a whole week thinking about how to write a history based exclusively on objects. Students were prompted to bring a mystery object from the past that their fellows students would struggle to identify. We found ourselves confronted with a wild collection of diverse items – from old scientific instruments, to nautical devices, coins, and old documents.

By explaining what the objects were once used for, the students practiced the telling of the past. In almost all instances, that also involved linking the item in question to their family history and/or to larger historical trends or periods. History suddenly took on a personal dimension – not an abstract narrative about the past but something that mattered to the students, subjectively and personally.

… and so?

The advantages of interactive teaching are clear, but only if we take the time to design this properly. In addition to the enhanced outcomes already mentioned, interactive teaching provides the lecturer with instant feedback on where students stand, individually and collectively, as well as continuous, real-time information about their progress. From my experience, interactive teaching has worked best when combined with more traditional forms of content delivery. Traditional lecture structures remain ideal for setting the frame for student learning, defining expectations, ensuring everybody is on the same page, and summarising outcomes.

At the same time, I also don’t think that interactive teaching will solve all the challenges we currently face. While attendance at my lectures may be higher than average, a worrying number of students will not show up to lectures at all, interactive or not. Moreover, as Dirk rightly points out, interactive lectures are pretty much impossible to record. To date, students relying on lecture recordings could get around this by enrolling in units delivered traditionally. Yet as more colleagues flip the classroom or adopt partial or fully interactive teaching methods, this will increasingly become a problem. There is no easy solution. Avoiding clashes and making lectures compulsory may work for some, but it will leave behind those students with other commitments as well as those who cannot attend lectures due to illness or disability.