In Semester 1, 2020 among the many challenges with rapidly going online was how to modify complex assignments to achieve the same learning outcomes and still facilitate deep learning and engagement with learning material.

In CSCD3076, the final assignment is a group case-based project which runs across 7 weeks of semester supported during tutorials. Each group of students is allocated one case study from a set of 4. Groups work together to consider assessment data, plan goals, recommend intervention and review progress. Student learning is scaffolded with exemplars that are presented each week. Students learn about clients who have different disorders (Cerebral Palsy, Autism, Down syndrome) and who have a range of ages and communication needs. They need to create additional details about their client to enrich the case study. It is a complex assignment which requires support from lecturers and tutors during tutorials with opportunities for formative feedback. Student groups present their final product in week 13 for formative feedback from both staff and peers. In previous years, it has been challenging to ensure that students provide meaningful feedback which is valued by peers.

In translating this to an online activity, it was clear that running it live via zoom would be less than ideal and would not necessarily achieve the learning objectives. Therefore, the live student presentation activity was redesigned to be pre-recorded presentations. The challenge was to ensure student engagement with the process if it was online. The final process was as follows:

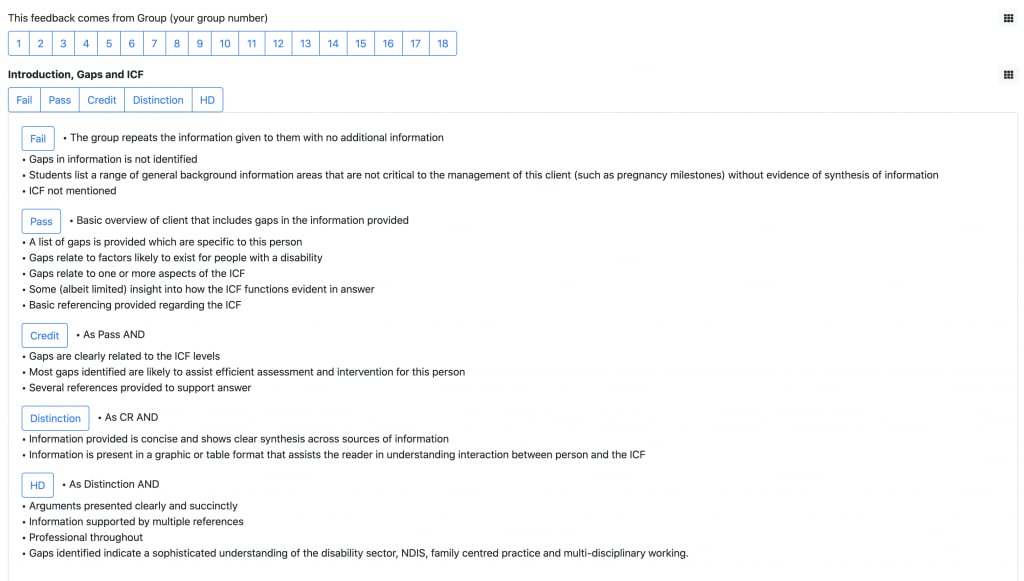

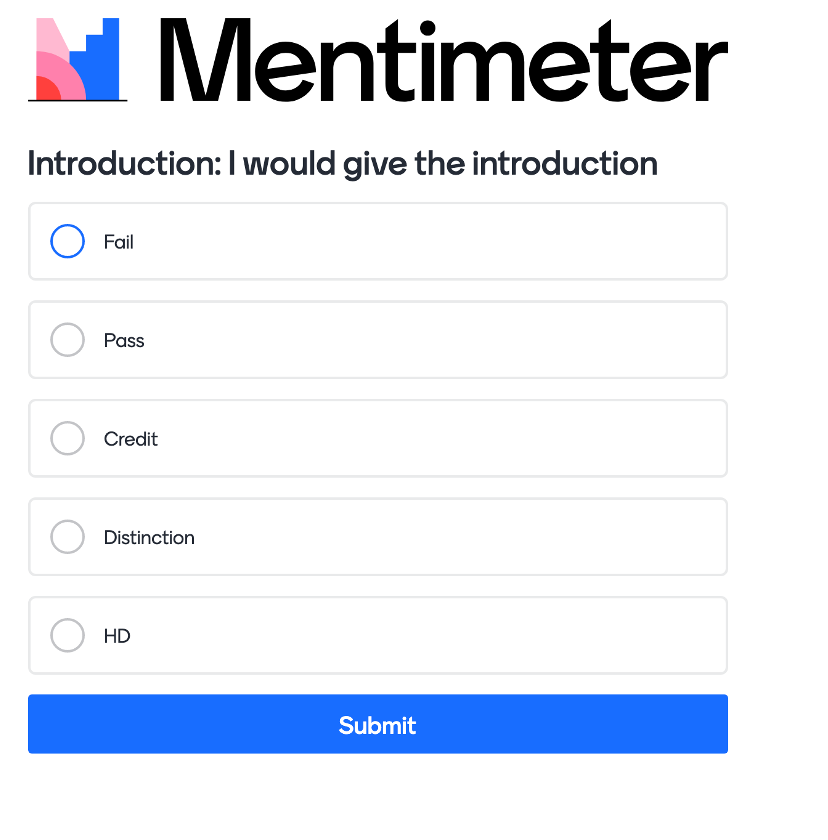

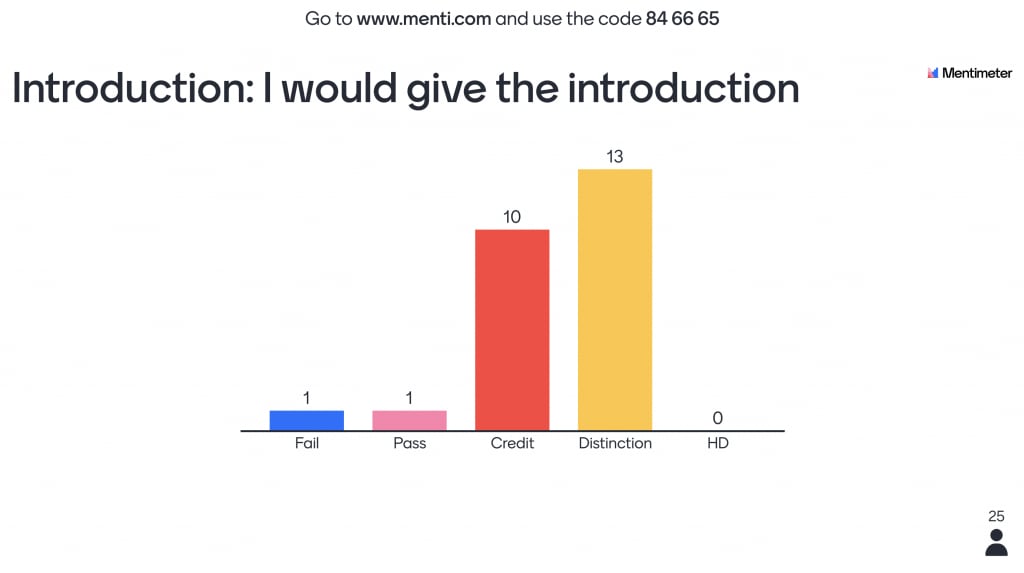

Step one involved the lecturer providing two exemplars of presentations about one of the exemplar clients. The two presentations were virtually identical in content and featured very attractive slides. They were designed to demonstrate some of the typical errors that were seen in previous cohorts – some errors were more subtle and nuanced than others. Students were invited to rate these on a Mentimeter poll and to provide comments.

.

.

After they had submitted their own rating, they could view their peers’ responses in Mentimeter. Once a significant number of students had responded in Mentimeter, the lecturer posted her own rating of each exemplar as a recorded video to not only show the grade but also discuss why that grade was given.

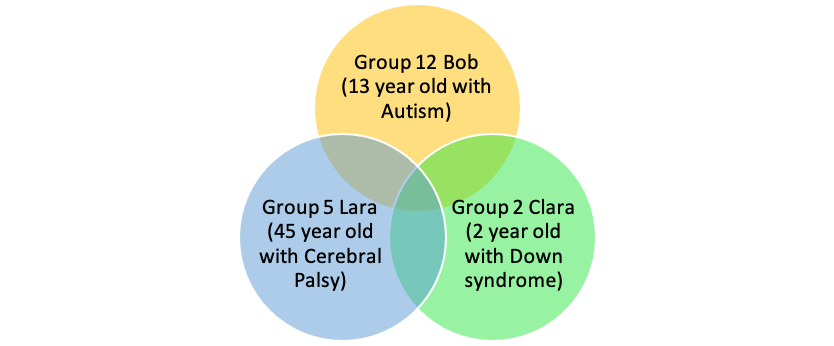

Step two, involved allocating student groups to a triad. Each triad included a range of cases.

The groups uploaded their presentation to a password protected folder on OneDrive prior to the lecture. During the 2-hour lecture time, groups were required to view the presentation of the other groups in their triad and provide feedback using an SRES form which was based on the marking rubric.

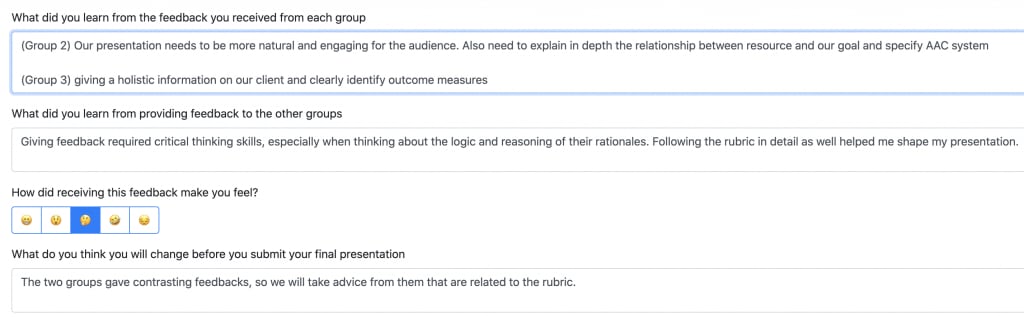

They were also provided with formative feedback from their tutors via SRES. During the tutorial time, students met in groups to review their feedback and reflect on it using another SRES form.

The final step for the students was that they were able to modify their presentation before submitting it later that week. Their revised presentation could be up to 15 minutes long to allow them to incorporate feedback and their own reflections in one additional slide.

In reflecting on my learning objectives for the students, I wanted the students to engage in deep critical thinking about their own client over a number of weeks in this online environment. Martin & Bolliger (2018) highlight key factors for student engagement in online courses including using authentic activities. Their respondents’ highest rating was for working on realistic scenarios and applying content (e.g., case studies, presentations, client projects). My goals for the face-to-face version of this task included using authentic activities much as they will do in clinical practice and also learning from their peers about a range of clients. In order to ensure this objective translated to the online format, I was concerned that the students wouldn’t provide peer feedback or wouldn’t value the feedback they received. I therefore incorporated marks both for providing feedback but also dependent on their peers’ perception of the value of their feedback.

Pedagogically, I was guided by the work of Hamer et al (2008) and his “contributing student pedagogy” in attempting to set up my classroom as a learning community so that students could view themselves as being on the same journey as their peers. This seemed particularly important during the current pandemic where students are isolated and possibly lack motivation to engage in online learning. In designing this assessment, particular detail was given to the guidelines recommended by Søndergaard & Mulder (2012). SRES met Søndergaard & Mulder’s criteria of being simple to use, accessible and customisable and using the triads met their criteria for rule-based distribution.

Overall the feedback from students was positive, with many commenting on how helpful they found the feedback and the process. Sixteen of the 18 groups reflected on the feedback received. After all assignments had been submitted, I surveyed the group and received mostly positive responses. Students reported that it was a positive learning experience that allowed them to improve their work, increase their motivation and use critical thinking. Students described how they analysed how the two exemplars were different even though they were superficially similar. They found peer insights “eye opening” and identified that they had made changes to their presentation from the feedback received. They found teacher feedback the most valuable, but did also report learning from both giving and receiving peer feedback. They did however, report confusion if instances of peer feedback differed from each other or from teacher feedback, frustrations about working online in general and a desire for one of the exemplars to be “perfect” so they could use it as a model. From an examiner point of view, it was sometimes challenging to provide feedback that would allow the students to improve their presentations in just a few hours. For some groups this was just about getting over the line to pass the assessment while for others it was small tweaks to improve an already good piece of work.

Overall, this was an exciting experience in modifying an already complex assignment into an online form that achieved the same learning objectives and seemed to maintain the sense of a learning community.