This post explores the first of the seven Principles for the (re)development of Learning Spaces at Sydney. Principle 1 is foundational, asking us to take an activity-centered approach. This is because learning is mediated though what we do, by our thoughts and our actions, which are in turn influenced by our learning environments and the broader contexts of our lives (Bonderup Dohn, Hansen & Hansen, 2019; Goodyear, Carvalho & Yeoman, 2021; Lave & Wenger, 1991). At Sydney, we are committed to teaching in ways that invite active learning. Not activity for activity’s sake, but the thoughtful application of knowledge building (Scardamalia & Bereiter, 2005). We have chosen to use the language of knowledge sharing, knowledge construction, and knowledge creation as described by van Aalst (2009) to unpack the thinking behind this practice below.

Knowledge sharing

Knowledge sharing, rather than sharing of information, happens when both parties understand the details and significance of what is being shared. Sharing can be formal (i.e., a lecture) or informal (e.g., a YouTube video demonstrating a skill). Knowledge sharing is distinguished from knowledge construction and creation by the emphasis on the introduction of information and ideas, rather than interpreting, evaluating or developing them. That is, the act of sharing does not result in changes to what is shared, it is not a reflective form of sharing.

Knowledge construction

Knowledge construction is the process through which students solve problems and develop an understanding of concepts and phenomena. It involves students making ideas meaningful in relation to what they already know within their current contexts. This notion is supported through questioning, interpreting and evaluating new information, and sharing, critiquing and testing ideas at different levels (e.g., conjectures vs explanations of concepts and/or causal mechanisms). Knowledge construction is effortful and reflective and can be done individually or in groups. It results in deep learning or conceptual change in complex but established domains of knowledge.

Knowledge creation

Knowledge creation focuses on the development of new ideas to sustain innovation. It flourishes where creativity is valued, and promising ideas can be selected for further development. Knowledge creation requires collective responsibility for knowledge advancement, authentic problems, epistemic agency, improvable ideas, an ability to ‘rise above’ and the constructive use of authoritative sources. Knowledge creation depends on productive discourse to maintain social cohesion, goal setting, deepening inquiry, and support for ideas already understood by some. The act of coming to know is mediated through the co-creation and sharing of new objects or ideas within and across communities.

Connecting theory and practice

What does a commitment to knowledge sharing, knowledge construction, and knowledge creation look like in practice, and how does the designed environment participate in the daily, weekly, and semester long unfolding of valued teaching and learning practices across campus? These two questions pose related but distinct challenges. The first is an educational design challenge, the second an architectural design challenge, and one way of addressing both challenges simultaneously is to take an activity-centred approach. As such, a good place to start is by asking,

“What will your students be doing today?”

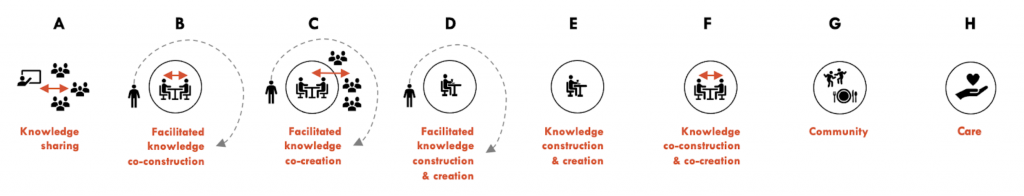

To support meaningful discussions about learning activity across disciplines and professional boundaries we developed a set of visual representations detailing valued forms of learning activity based on the theory presented above and the Principles Guiding Education at Sydney

Valued forms of learning activity

We have deliberately chosen to embed a whole-of-student and whole-of-campus perspective into the planning and delivery of educational infrastructure. Working with the complete set (Fig. 1) ensures that even when the focus is on a specific sub-set, we are always conscious of how developments in one might impact others. Keeping the set intact also ensures that opportunities to support the full range are taken whenever possible, and less visible aspects are considered when new spaces are being designed. For example, a broad commitment to project or team based learning (Form B) increases the need for informal learning spaces suitable for group work (Form F). Care (Form H) is formally accommodated in student services, but we can choose to weave it into thoughtful designs and acts of kindness anywhere people gather.

Form A (Knowledge sharing)

A one-to-many relationship in which ideas are presented with time for questions and answers. The presenter could be an educator or student. This form’s key requirements include the audience being able to hear a single voice, and to have individual seating with a clear line of sight to a shared point of visual attention.

Form B (Facilitated knowledge co-construction)

A peer-to-peer sense-making relationship with access to support from an educator. Key requirements include group seating, an ability to move between and within groups, and access to tools for shared sense making (e.g. writeable surfaces).

Form C (Facilitated knowledge co-creation)

A peer-group to cohort relationship in which individual groups present new contributions to knowledge to the entire class. This form requires time for shared sense making or knowledge co-creation based on general questions or formal peer feedback. Key requirements are the same as Form B with the addition of support for presentations from peer-group to class.

Form D (Facilitated knowledge construction)

Individual sense making with the support of an educator. Typically, this involves the use of specific tools or instruments. Key requirements include access to space where tools or instruments are housed and scheduled time for supervised practice without interruption.

Form E (Knowledge construction and creation)

Individual sense making on one’s own. Key requirements include access to space suitable for reading, reflection, and practice that does not involve educators, peers, or specific tools.

Form F (Knowledge co-construction & co-creation)

Peer-to-peer sense making and knowledge creation without the support of an educator. Key requirements include access to group spaces with wi-fi and power.

Form G (Community)

Student-led social and co-curricular activity including making or sharing meals, and participating in interest groups, societies, performances, exhibitions, or sports. Key requirements include safe and generous access to a wide range of settings across campus.

Form H (Care)

Access to student-centred support services including counselling, peer-mentoring, academic and administrative support services, and a whole-of-campus commitment to care for individuals and groups. Key requirements include visible points of access across campus that afford privacy where appropriate.

Improving the alignment between learning spaces and teaching practices

We are working to improve access to learning spaces that accomodate valued learning activity across campus. However, access to new or redeveloped spaces will not automatically change teaching practices and mapping a unit of study at a high level using the images above can help you understand your spatial needs. Thinking about what your students will actually be doing in the time you share is an excellent place to start.

For example:

- Are you making the most of time scheduled into seminar rooms? Does facilitated knowledge co-construction (Form B) accurately describe what you have planned?

- What of time scheduled into a lecture theatre? Is it all knowledge sharing (Form A) or could you accomodate facilitated knowledge co-construction (Form B) by requesting a larger lecture theatre and leaving alternate rows empty to facilitate movement between groups of two or three?

- A learning studio is a great place for sessions dedicated to facilitated knowledge co-creation (Form C) but there are plenty of creative ways to support the sharing of group work both with and without the help of technology. Group presentations can be accommodated in a lecture theatre, a seminar room can accomodate poster sessions, and large groups can be divided into parallel online streams and accommodated effectively in Zoom breakout rooms.

Finding practical support to put good ideas to work in the spaces where you teach

Educational Innovation is home to a vibrant group of educational designers committed to helping you integrate the principles of Universal Design for Learning (UDL) into your teaching and learning practice. Follow the links below for more information.

- The Designing for Diversity Canvas resource offers examples of how colleagues have integrated UDL into their practice

- Read about ideas for inclusive assessment using Designing for Diversity

- Book a 30 minute Designing for Diversity consult

- Book into a 90 minute Designing for Diversity workshop

References

Bonderup Dohn, N., Hansen, S. B., & Hansen, J. J. (2019). Designing for Situated Knowledge Transformation. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429275692

Goodyear, P., Carvalho, L., & Yeoman, P. (2021). Activity-Centred Analysis and Design (ACAD): Core purposes, distinctive qualities and current developments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 69(2), 445–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09926-7

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2005). Knowledge Building: Theory, Pedagogy, and Technology. In The Cambridge Handbook of the Learning Sciences (pp. 97–116). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511816833.008

van Aalst, J. (2009). Distinguishing knowledge-sharing, knowledge-construction, and knowledge-creation discourses. International Journal of Computer-Supported Collaborative Learning, 4(3), 259–287. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11412-009-9069-5