Hong Lou Meng (紅樓夢), also known as The Dream of the Red Chamber, is one of the most celebrated works in the canon of Chinese classical literature. In semester one 2025 I taught the novel as a tutor for CHNS2633: Topics in Chinese Literature. Written in the eighteenth century by Cao Xueqin (曹雪芹, 1710–1765), The Dream of the Red Chamber offers an extraordinary exploration of family, desire, illusion, and social decline. With its intricate narrative structure, philosophical depth, and more than four hundred named characters, the novel presents both a rich resource and a significant challenge for students encountering it in an Australian university setting.

My students have diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds, and the unit placed significant demands on them: engaging with a text that was both culturally distant and conceptually unfamiliar, while also learning discipline-specific interpretive methodologies. I decided on an approach blending close reading and creative adaptation, the former helped my students slow down and develop disciplinary attentiveness, and the latter invited them to consolidate understanding by actively reshaping meaning.

Teaching complexity through close reading

As both a teacher and an admirer of the novel, I was keenly aware of the risk that students might feel overwhelmed by its scale and cultural specificity. My primary pedagogical goal was therefore to make the text accessible and meaningful for students from diverse linguistic and cultural backgrounds. Given the novel’s wide scope (120 chapters filled with intersecting storylines), I began by helping students familiarise themselves with the main plots and key characters. Once this foundation was in place, I shifted the focus from “what happens” to “how meaning is created.” I sought to design a teaching strategy that would enable students not only to follow the plot, but to engage with its language, emotions, and cultural subtleties.

Close reading formed the core of this strategy. Rather than rushing through, students were required to attend carefully to textual details that revealed the novel’s distinctive narrative voice, emotional texture, and cultural references. This approach supports the development of skill relevant beyond my classroom; when we encounter complexity, structured attentiveness can be more productive than simplification.

Bilingual close reading and translation as a comparative learning strategy

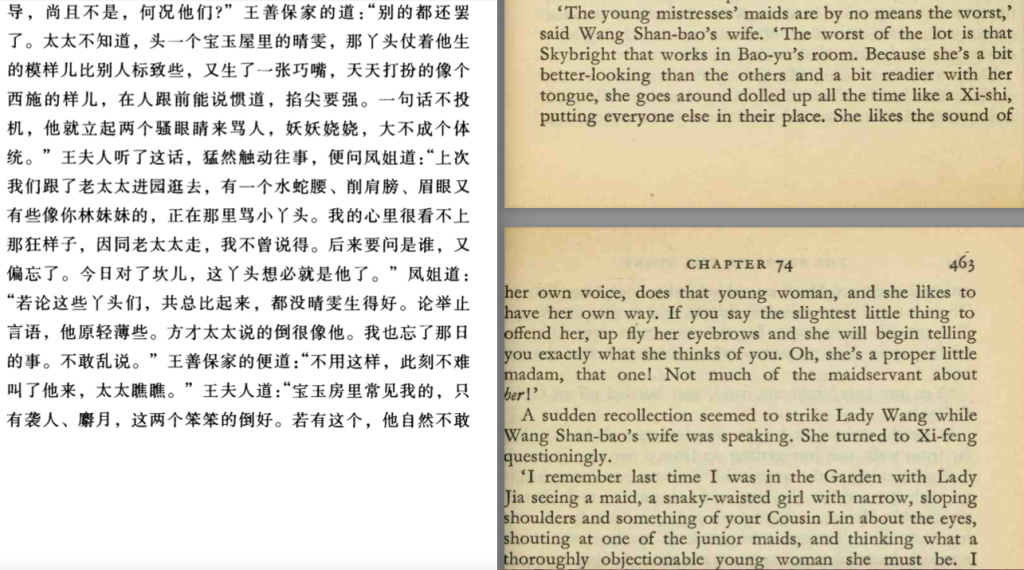

For the first eighty chapters we engaged in bilingual close reading, using both the original Chinese text and English translations. This method allowed students to experience the rhythm and texture of the original prose and poetry, while examining how meaning shifts across linguistic and cultural boundaries. However, this process also introduced one of the most significant challenges. Many students were confronted by how much nuance, emotional intensity, and poetic resonance could be lost in translation. As one student reflected in the post-course survey:

“One of the main challenges for me was how much the beauty and depth of the original Chinese get lost in translation––especially the poetic imagery, symbolic couplets and subtle dialogue. When reading Dream of the Red Chamber in English, a lot of the emotional weight and cultural richness felt diluted.”

Such reflections underscore the central challenge the novel poses for cross‑cultural readers: how to grasp the essence of a text deeply rooted in a particular language and culture. Rather than treating this tension as a problem to be resolved, I framed it as an opportunity for inquiry. I introduced two additional English translations and encouraged students to compare how each rendered the same passages. Through guided discussion, students explored how translation choices shaped tone, emotional impact, and cultural emphasis. Many noted that each version highlighted different dimensions of the original text.

Through bilingual close reading, students developed a sensitivity to tone, imagery, and symbolism, discovering how subtle linguistic nuances could reveal emotional complexity and philosophical depth. Pedagogically, it also served a broader purpose: by placing multiple versions of the “same” text side by side, students learned that expert knowledge is often constructed rather than fixed.

Close reading as a bridge between cultures

Over time, close reading became more than a literary technique; it functioned as a bridge between languages, cultures, and modes of thinking. By slowing down and attending to detail, students were able to connect emotionally and intellectually with a text that initially felt remote. They came to understand the novel not simply as a historical artefact, but as a meditation on impermanence, emotion, and social change. This shift was evident in student reflections. One wrote:

“For me, the best part of this unit was getting to explore Dream of the Red Chamber in such a detailed and thoughtful way. At first, I honestly felt nervous because the language and references were hard to follow. But through weekly discussions, reading breakdowns, and the patient guidance from both Josh and Ella, I gradually began to understand the deeper meanings behind the text. Their support really helped me engage with the novel’s characters and themes on an emotional level. This unit made Chinese literature feel much more alive and personal to me.”

Such feedback suggests that structured, supportive engagement with complex texts can foster both confidence and emotional investment. By approaching the work through both linguistic precision and interpretive openness, students not only deepened their understanding of Chinese classical literature but also developed confidence in engaging with complex ideas across cultural boundaries.

Creative adaptation as learning agency

For the final forty chapters I deliberately shifted my teaching approach from close reading to creative adaptation, providing chapter summaries and inviting students to reconstruct or reimagine the novel’s ending. This task encouraged them to think critically and creatively about narrative structure, thematic coherence, and philosophical intent: which elements best express the novel’s vision of illusion and human fate? What might be condensed, reshaped, or reinterpreted to achieve greater resonance?

This pedagogical shift reflects a broader principle: once students have developed sufficient disciplinary literacy, granting them interpretive or creative agency can deepen learning. Moving from analysis to creation required students to synthesise ideas and make informed choices rather than reproduce established interpretations. Students responded to this task with enthusiasm, producing alternative endings that explored tensions between fate and agency, illusion and reality. Many demonstrated a sophisticated grasp of the novel’s emotional and moral complexity, suggesting that creative engagement can effectively consolidate analytical learning.

Reflections on teaching across cultures and disciplines

Teaching The Dream of the Red Chamber through a combination of close reading and creative adaptation proved particularly effective in Australian classrooms where many students encountered Chinese classical literature for the first time. Close reading grounded their understanding in language and context, while creative adaptation encouraged reflection, empathy, and intellectual risk-taking. More broadly, this experience reaffirmed my belief that complex and culturally unfamiliar material can become a powerful teaching resource when approached thoughtfully. By scaffolding complexity, valuing interpretation, and eventually inviting students to create meaning for themselves, educators can help students move from uncertainty to confidence. Teaching intellectually demanding material is therefore not simply a matter of transmitting knowledge, but of cultivating habits of reading, thinking, and imagining that students can carry into diverse and multicultural contexts.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to my supervisor, Josh Stenberg, for his guidance and constructive discussions on teaching pedagogy.